This is one in a series of short stories I've been writing during my own coronavirus quarantine. You can find the complete collection of fiction written especially for this blog here. My books are available on the Amazon Kindle, for sale or for reading via Kindle Unlimited.

__________

But she wasn’t.

Her family owned a ranch, up near Dime Box, in central Texas. It ran to a full section, 640 acres. They ran cattle on it, had for five generations. Everything was on the agriculture exemption, except for a tiny house near one corner with a miniature garden, worth hardly enough to knock down.

Life was never easy. When her father wasn’t grading for hay, checking the perimeter fence for rustlers, or driving the herd between seasons, he was snipping off the balls of the young bulls and selling the year-olds to a processor he said was in “Wyoming.” He also fought a running battle against feral hogs that tore everything up. There were no roads in the section, just trails, as it had been since the 19th century when “Big Jim” McPhail, son of Irish immigrants, bought it out of some Mexican family’s bankruptcy.

Andy had no brothers. It was something her parents never talked about, within her hearing. When she was 10, however, she heard her parents discussing the idea of “adopting” an immigrant child. Preferably one from the Ukraine. Daddy didn’t want the land going back to the Mesicans. That was his word for them.

They didn’t do that. Daddy decided Ukrainians were Russkies.

They finally got a TV when Andy was 12. It was when her mother turned sick with a cancer. A surgeon in Austin operated on her. For weeks after she was very quiet. The TV was put in her room and played a succession of church shows. When momma recovered, the TV and the preachers stayed, even though they started going back to Sunday services. Prayer books and statues started appearing in the house, “gifts” her daddy said from the TV preachers who loved her momma so much.

Andy didn’t know she was pretty, but she was. She became a muscular, full-figured girl, curves kept in by a strict diet of red beans and rice. She wore chambray shirts, jeans, and boots, even to Fairview High School. She didn’t take the bus. She walked. She didn’t have any friends and didn’t want any.

They all piled up daddy’s good truck with sandwiches and Big Red. Andy sure the dogs had food to last a couple of days. They turned on lights so the hogs wouldn’t figure out they were gone. They left very early that Saturday morning, before the summer sun came up.

They hit the big road near Waco, which was very scary even after her daddy explained it. Andy held close to her mother until they hit 35W through Ft. Worth. They entered Oklahoma near Ardmore, skirted Oklahoma City, and took the 44 into Tulsa. There was a huge parking lot to welcome them, and many good people. The McPhails didn’t know they needed tickets. They planned to watch the President on a big screen outside. But then they were allowed right inside the arena.

It never went up.

That Wednesday, Andy didn’t feel well. She felt worse Thursday, and her momma wasn’t feeling great, either. By the weekend, daddy was laid up with whatever it was. Andy was feeling a little better by Monday, well enough to know her parents were very sick. She picked up her daddy’s phone and called the 911, which sent an ambulance.

She would never forget it.

Andy had taken to having her daddy’s phone with her, on the tractor, and when the phone rang, she jumped a little.

“Ms. McPhail?” asked the man. He sounded foreign. “Andrea McPhail?”

“Yes,” Andy said. “This is Andrea McPhail. Are you calling about my mother and daddy?”

Andy didn’t know what COVID-19 meant, all she heard was dead. “Arrangements?” she asked.

“For their funeral, Ms. McPhail. Your parents have died.”

Andy didn’t know what to say. She didn’t know what to think. In two weeks, she went from being the protected, much loved daughter of two wonderful parents, to what, an orphan? She had read about orphans in school, how they went about with empty bowls asking for more gruel.

Andy thanked the doctor and rode the tractor back to the house. She went through her father’s desk, looking for names of people that could help.

One name leapt out at her. She called her parents’ preacher near LaGrange, Rev. Elderflower. He was filled with sorrow, but not surprise. He knew where St. Mark’s was, and said he’d handle “the arrangements.” He said, “it was probably the Covid.”

Andy spent a half hour on the phone with daddy’s preacher, telling him how lost she felt. Near the end the preacher said he would send someone to talk with her. She explained about the chores. The preacher said his own son would come the next evening. He asked if she had anything in the house. She said no. Rev. Elderflower said his son would bring dinner.

The next evening, a handsome young man exited a very comfortable-looking sports vehicle on high wheels. He brought bags of fried chicken with him, and fixings. Andy only had fried chicken at the church picnics.

This tasted just the same.

Andy was well into her second helping of soda when the young man asked the question.

“What happens to the place?”

Andy said she didn’t know. She motioned to her daddy’s desk, where the papers were strewn about. She explained about looking for his daddy’s number, and how she didn’t know where everything went.

“That shouldn’t be necessary,” Gomer Elderflower, spying her daddy’s phone on the kitchen table. “I’m sure it’s on his speed dial. Mr. McPhail was big for the church.”

“Yes, he was,” she said.

“Mind if I look around?” asked the young Elderflower, giving the papers a squint, like she’d seen on a hog once before daddy killed it with his shotgun.

“Go ahead,” Andy said. She was tired. She wanted badly to close her eyes. Dawn came early.

“We’re your family now,” Rev. Elderflower said.

Andy learned her parents died intestate, that is without a will, but it wasn’t hard for a friend of her new husband to have her named the heiress.

—

This could have gone south in a hurry if I hadn’t intervened.

My name is Dorothy Goodrich. Dot to you. I’m a clerk in the office of Frank Micha. He’s the county attorney here in Fayette County, that’s district attorney to you. LaGrange is the county seat.

We know all about the Elderflowers here in LaGrange. Unity Baptist Church is their place. They’ve got a cheap metal building laid out on a concrete slab by Highway 71, just short of the Walmart. They managed to keep themselves outside the city limits, but everything’s in the county.

What most troubled me was young Gomer’s marriage certificate to the young victim, a weekend ceremony in the church offices. The next Monday I saw another transaction, Elderflower LLC taking the transfer of 640 acres up in Dime Box from Mr. & Mrs. G. Elderflower for $1.

On the other hand. It’s a church. You don’t go against any church in LaGrange. There’s the law and then there’s God’s law, which apparently makes everything all right if you call yourself a preacher. Besides, it’s usually old widows. But this was an 18-year old kid. They were stealing her inheritance in broad daylight before it even had time to settle, probably before the dear girl had time to know how much it was. I figured there was $4 million worth of land there, minimum. Cut that into 10-acre ranchettes, sell some of ‘em quick to Austin software salesmen, put the rest out on time to Houston goobers who won’t make payments, it’s better than a well over Eagle Ford shale.

I told Frank about it that morning, before he went to lunch. “We got to get Reverend Elderflower,” I said. “We got him dead to rights. Got him damn good. Him and his damned son both.”

Thank God Janet Reynolds wasn’t working at the Bistro that day. He loves to flirt with her and doesn’t get anything done. But her boy had a dentist appointment. Frank must have read the papers.

Frank came back spittin’ mad.

But what could we do, exactly? Have the marriage annulled, Frank said. Get that girl in here and tell her what’s happened to her. The land transaction to the developer would go through, that couldn’t be stopped, the land was lost. But an annulment would mean the girl gets the money, every dime owed to her, which with the Elderflowers out of the deal might come to about $6 million once he and the developer had a chat.

She got the annulment. We agreed not to prosecute. Long as she was given her due it was no harm, no foul. She couldn’t have done better than that development anyway. Single girl, alone, out on the prairie. She would have been out of business in a year, skunk broke, selling that place on the courthouse steps. Probably to Mesicans.

I kind of took her in hand. I introduced her around, got her an apartment. Got her some books. Even got her cable TV. Christ, the girl was a millionaire. It was mighty slow dawning on her, though.

When A&M Kingsville was ready to hold classes again, Andrea McPhail was in the front row at Hoggie Days, which is what they call freshman week there. She was a business major now, not wildlife management. I helped her sign a paper over to Prosperity Bank, a trust account that would protect the principal for her while she got herself an education. She and the bank both offered to pay me for my time. The bank finally insisted. I took $1.

Prosperity did all right. By the time she graduated the nut wasn’t $6 million. It was $8 million. Half went into her McPhail Foundation in Austin, where she bought a small place. It pays her a salary as director. The other half is her retirement. She won’t worry about money, ever.

Last time we talked, she said the feral hogs are coming for the cities, but she’s going to knock them back.

She’s going to make a difference in the world, that girl.

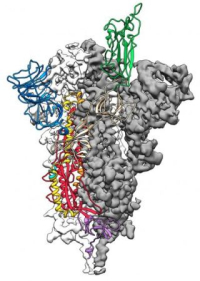

And to think it all started with a virus.