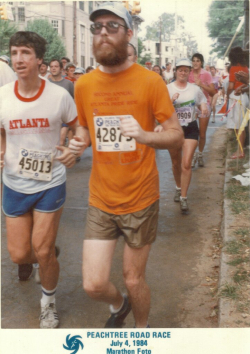

You’re looking at the face of an old white guy and wondering about the headline.

You’re looking at the face of an old white guy and wondering about the headline.

Here’s the story.

I was brought up racist, on Long Island. I didn’t think that was the case, but I know now it was. I knew people like Roger Stone, Eugene Delgaudio and David Keane when they were kids. That’s because during the height of the Vietnam era I was part of a group called Young Americans for Freedom, a right-wing agitprop created by William F. Buckley when the SDS was getting started.

I’m not proud of it. I got falling-down drunk at age 16, and the hangover lasted until the day after school started. I told my parents I was sick.

We weren’t rich, but we had a lot of white privilege. It helped me get off Long Island and into Rice University, even though my parents had saved nothing for college. It got my dad a small business loan when he fell through a false roof and became disabled. The parents of the girl I married turned out to be well-off too. Most Rice parents are.

I was blind to my own good fortune. I saw myself as an idealist. I went to Northwestern, got a job at a business newspaper, and covered the end of the Houston oil boom.

Little did I know how big a bargain that was.

I’d known a few black folks at Rice, but only casually. The first black man I met here lived next door to my “new” house (built in 1923). He wore a white, sleeveless muscle shirt and white pants. He suffered from vitiligo, so there were patches of white on his face, on his neck and on his arms. He came out around 10:30 each morning, pushed a walker down to the sidewalk, went to each end of his property line, then returned to his stoop. This workout took most of an hour. At the end he was winded.

“My dad fixed TVs,” I said proudly.

“They were slaves,” he said.

John Flint was born in 1883. His parents had indeed been enslaved, and he lived through the entire Jim Crow era. He turned 100 that October. The workouts would get him to his birthday party. We rode our bikes there. It was held in a large hall at Agnes Scott College. He had worked there for 60 years. There, every living ex-president came to celebrate Mr. Flint’s life, along with all 8 of his children, all of them successful. His wife had passed just a few years prior. He lived to be 102.

I soon learned Winter Avenue had a “block club,” which met every month at one neighbor’s house, and whose aim was to fight crime, so I joined. Block clubs like this remain a primary means of fighting crime without violence. If you know your neighbors, you know who your neighbors aren’t.

There, our secretary had been a founder of the DeKalb NAACP, who came back from World War II wanting nothing more than to become a TV repair man, like my father. He was denied the opportunity because of the color of his skin. He founded the NAACP group in 1955, when to do so was taking his life in his hands, and he kept our block funds in a sock. Each adult put in $1 each month, and a family that suffered a death got $50. This is how life insurance works.

It turned out that most of my new neighbors were deacons and bishops, church elders and their wives. These were the true “Greatest Generation,” the people who won the Civil Rights struggle. These were the foot soldiers of freedom.

They raised me, not physically but morally, in all the ways that matter. They taught me the use of religion and the importance of community. They taught me about faith and about family. One could do Jesus’ miracle of the loaves and fishes – I watched her do it myself. Another lived as Jesus did, complete with the carpentry. He laid the tile floor of my kitchen. Another, who was John Flint’s daughter, nursed her mother, sister, husband and then a daughter through their fatal illnesses, while traveling to the north side each day and doing the same for old white folks. There were so many others, and I miss them all terribly.

Because of the block club, the crime rate on Winter Avenue back then was 30% lower than on adjacent streets. Our meetings drew regular visits from Atlanta and Decatur police community relations officers, who shared the numbers. The club had come together because Decatur treated our street like it was in Atlanta, and Atlanta treated it as if it were Decatur. In old wire-bound maps of the time the street wasn’t shown, because it was at the map’s inside edge, hidden by the wires. My Decatur neighbors went to different schools, had different congressmen, different legislators. At the head of our street the eastbound highway ran west, and the westbound ran east, as the federal routes wound behind our MARTA station.

Things began to change after the 1996 Olympics. Kirkwood was gentrified. South Decatur became Oakhurst. Real estate agents moved the color line after Tom Cousins bought the East Lake Country Club, had the nearby public housing project torn down, and replaced it with mixed-income housing and my YMCA.

My white neighbors are fine. The air today is alive with the sound of their children. My own kids are now grown. They had only black children to play with, but they played well together. They were the minority in school. I like to think they have good values.

The point is that my first Winter Avenue neighbors were better people than me. Mainly it was because they had to be. As grandparents, several saw daughters boomerang back home, their own kids in tow, and they raised those kids without complaint. Their reward was gentrification. When their children sold their houses, upon their death, those families got cash to be treated as an inheritance, money that meant college in black suburbs like Lilburn, and values to make the most of those opportunities. None sold to blacks. Nothing segregates like property taxes.

All lives should matter, but if black lives don’t matter then no lives do.

The current Klan rising, for that’s what it is, will fail, as the last one in the 1960s failed, because millions of white folks know it’s evil and wrong. Granting equality doesn’t mean we get less. It means more for everyone. It means less crime and less human talent wasted. It means more people growing up with the right values, and more wealth for everyone in this high-tech age.

I’m an exception among my own people. I have white family and white friends who still don’t get it. They talk about “those people” as though skin or ethnic heritage was a genetic distinction, as though poverty makes someone inherently less.

Maybe such attitudes will always be with us.

But I will no longer tolerate it.

My grandfather sold out to a developer while he was still alive, with the proviso that he could remain in his house for the rest of his life. (A small block of apartments stands on the lot in Macon where my grandfather’s home once stood.) It would’ve been good if the homeowners on Winter Avenue could’ve seen some of the money their lots were worth during their lifetimes, but I guess nobody told them such a thing was available.

My grandfather sold out to a developer while he was still alive, with the proviso that he could remain in his house for the rest of his life. (A small block of apartments stands on the lot in Macon where my grandfather’s home once stood.) It would’ve been good if the homeowners on Winter Avenue could’ve seen some of the money their lots were worth during their lifetimes, but I guess nobody told them such a thing was available.

Some of my neighbors sold out before their death.

But there was no better place for them. Many of my neighbors lasted well into their 90s by aging in place. Jessie Shank lived to 96. Palmer Harris close to the same. Edna House was 101, just short of her father who lived here until 102.

When you get to be my age, which is 65, you renegotiate life. You realize what’s important, and what isn’t. Friends, neighbors, loved ones who come to you to enjoy their youth rather than to watch you die in front of them.

My Winter Avenue friends had good lives. Great lives. Right to the end of long lives. My ambition is to emulate their example.

Some of my neighbors sold out before their death.

But there was no better place for them. Many of my neighbors lasted well into their 90s by aging in place. Jessie Shank lived to 96. Palmer Harris close to the same. Edna House was 101, just short of her father who lived here until 102.

When you get to be my age, which is 65, you renegotiate life. You realize what’s important, and what isn’t. Friends, neighbors, loved ones who come to you to enjoy their youth rather than to watch you die in front of them.

My Winter Avenue friends had good lives. Great lives. Right to the end of long lives. My ambition is to emulate their example.