The 2016 election, and its aftermath, is less about millennials as a group than what Richard Florida, over a decade ago, called the “creative class.”

The 2016 election, and its aftermath, is less about millennials as a group than what Richard Florida, over a decade ago, called the “creative class.”

The creative class consists, as an old comic from college recounts, of those people “accused of wealth and guilty of education.” Anyone in a creative pursuit, whether that involves liberal arts or science and math, is part of the creative class.

Techies are part of the creative class. So are people like me.

The creative class, as a group, has different needs than the Organization Man William Whyte wrote about in 1956. For us, work isn’t something we do from 9 to 5. It’s what consumes us, what drives us. Our passion for what we do is a key to our productivity. Thus, we desire continual contact with one another, both online and offline. The center of our city is not downtown, but a research university, which may be in another part of the city or in a separate city by itself.

Creative class cities can be large, like Silicon Valley and Atlanta, or they can be small, like Athens and Davis, California. What they have in common is intellectual and physical density. They don’t need a port or a river. They are often creations of government, including Land Grant universities created by Abraham Lincoln’s government.

Creative class cities can be large, like Silicon Valley and Atlanta, or they can be small, like Athens and Davis, California. What they have in common is intellectual and physical density. They don’t need a port or a river. They are often creations of government, including Land Grant universities created by Abraham Lincoln’s government.

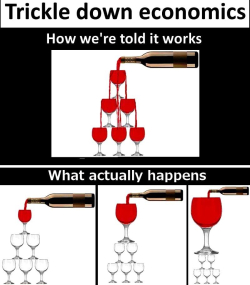

What the creative class, and the businesses we build, need is more human capital, and those things that draw human capital into the economy.

As a member of the creative class, I know of no one who voted for Donald Trump. Not one person. No one who lives near me, and no one who shares any of my values, voted for the man who got 46% of the vote and a majority in the Electoral College.

We know this because Hillary Clinton got huge majorities among non-white voters, regardless of education, as well as the creative class and still lost.

So here is the crisis. The government is in the hands of idiots because the idiots voted for it. What they wanted, and what they saw, in Donald Trump, wasn’t necessarily someone who would look out for them. What they saw, what they still see, is someone who will do everything possible to piss off the creative class, and try to kick us out of economic power.

Right now, the creative class in America is isolated to a few large cities, and to the centers of some others. The rest of our people are engaged in people that may serve the creative class, but which are subservient to it. These people see the future we’re building and they want to get off. They see no place in it for them or their kids.

The political challenge for the creative class is to convince these people that they do have a future in this new world, and that their children won’t be shut out of it. We can’t just wait for Trump to convince them there’s no hope at all, because the next step after that is violence, which will destroy the economy for everyone.

That starts with a truth about human capital.

Improving human capital requires social mobility, but too many members of the creative class have pulled up the ladder. Ideally, it should be as easy for a rich man to die poor as a poor man to die rich. This is what gives a creative society its juice, its discipline, and its hunger.

This means the technology industries must go on offense, on behalf of social mobility, and on behalf of the values that built them. Issues must be created that separate Trump from his supporters, and these issues need to be brought to the centers of his coalition, just as the Sagebrush Rebellion turned blue states red in the 1970s.

It’s easy to start with education, education that is of high quality, and free to those who can’t afford it. The K-16 environment demands more automation, even though many who consider themselves part of our class serve the status quo. That’s why people like Mark Zuckerberg keep pushing for charter schools. Control must be given to those who will focus on efficiency and real results, namely the discovery and training of talent into human capital.

Social mobility, as a call, is an issue that can bring over the 20% of Trump voters who might float back, if given a reason to. (In the ad to the left, the old men are said to be age 50. A good illustration of how far we've come in a century when we bother to look.)

Assure those outside the creative class that they are not about to become obsolete, and that there are better jobs waiting for them, is the key issue of our time. We will talk more about this over the next few weeks.

great information.

http://uonlibrary.uonbi.ac.ke/

great information.

http://uonlibrary.uonbi.ac.ke/

quite creative people.

quite creative people.

Interesting read, very unique

Interesting read, very unique