“A little patience and we shall see the reign of witches pass over, their spells dissolved, and the people, recovering their true sight, restoring their government to its true principles.” – Thomas Jefferson

As technology rose to economic power, from the 1970s through the 2010s, its political wishes were accepted by both parties. Barack Obama was essentially given power by technology in 2008 – his cloud infrastructure was Google-like – but technologists could have lived with Mitt Romney as well.

This changed in 2016.

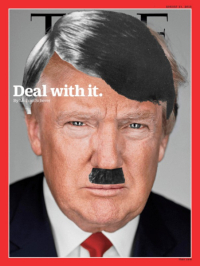

The political priorities of technology are human capital, free trade, political stability and a concern for the planet. Donald Trump opposes all these things, loudly. He sees capital in terms of money and physical resources. He is against free trade. He likes political instability. He has no concern for the health of the planet.

This is forcing technology to align itself with Trump’s political opponents, aiming at the complete destruction of the current Republican Party.

But there’s a second thing that must happen for such a realignment to happen. Trump’s political opponents must align themselves with technology, and accept the technology industry’s leadership over them.

This is the way it has always been. Just look at past political cycles.

Move on to Teddy Roosevelt. The union between Republicans and infrastructure was cemented gradually, as banks under J.P. Morgan negotiated with Theodore Roosevelt over a new balance of economic power. AT&T launched its “universal service” strategy in 1908, settling its anti-trust case in 1913, and Standard Oil was nominally broken up in 1909. Such settlements between capital and government became a new status quo, assuring rising manufacturers of low, stable costs, guaranteeing political power to Republicans until the Depression.

Think about FDR. Manufacturers did not cotton to Franklin Roosevelt right away. They didn’t like unions, for instance. But as the New Deal was moderated, and as manufacturers became central to Administration policy, groups like the Business Roundtable gradually aligned themselves with the new order. By the mid-1950s even Republican groups were accepting New Deal policy assumptions in the name of progress.

Politics, in other words, always follows the path of the dominant industry. It changes when the dominant industry changes. Oil is no longer our dominant industry. Technology is.

So what we are going to see in the next few years is technology slowly insinuating its interests into Democratic politics. The causes Democrats push will be made to align with technology’s priorities. No political movement can achieve political dominance for any length of time without the support of the dominant industry, and right now that’s Internet technology.

The priorities of technology are not the same as those of liberals. To the extent that this is true, as with visas, trade, and especially charter schools, it’s the liberal interest that will be jettisoned, not that of technology, if you want to achieve success. This is inevitable unless Democrats want to build a bridge to 1828.

Technology is not well-served by a trade war with China. U.S. technology is dependent on a stable Taiwan, and a complementary relationship with the Mainland.

Technology is not well-served by antipathy toward immigrants – it needs that talent.

Technology is not well-served by nation states taking absolute control of their domestic online spheres – such balkanization will cost money to fight.

Most important, technology cares less about physical resources like oil, which can be replaced, and political control over land, which is irrelevant, than it does with generating and maintaining trained minds and concentrated effort. Technology does care about climate change, because it can offer solutions to mitigate what’s coming and reverse what will follow, through biological science. But technology needs freedom of action to accomplish these aims, and Trump is not offering it that.

There are things technology will accomplish in these next few years that have no political content to them. Computing is becoming a visual medium, mediated by voice, rather than a text medium mediated through keyboards, mice, and tapping on screens. Technology is “breaking out of the box,” becoming ubiquitous, an essential element in everyday things, the Internet a surround used mostly by our machines rather than directly.

In general, however, technology will spend the next few years building a political infrastructure. This will include physical infrastructure like university chairs and think tanks, human infrastructure like troops dedicated to what technology wants, and most important, issues, aligned behind Democrats because Trump offers no choice.

No industry can come to permanent political prominence unless it is playing offense rather than defense. The next few months will see technologists quietly studying what peripheral changes it can push that are popular among groups Republicans now take for granted, especially working people. Fighting for those causes, facing opposition, and overwhelming that opposition on a state-by-state level will bear watching. It’s the 2010s equivalent of the Sagebrush Rebellion.

My guess is that, with these new issues, U.S. policy decisions will only be local ordinances. Technology has global political interests, and it will pursue them on a global basis, without regard to whether a local government is nominally “democratic” or “autocratic.” Those are labels. What matters to technologists are results, and they will demand results from politics as they do anywhere else. Failing to get them here, they will seek them there, and they will invest where they get them, guaranteeing eventual success.

Forget Trump. Prepare to welcome your new technology overlords.

Kara Swisher at Recode is not so sure:

http://www.recode.net/2017/1/23/14340518/what-would-steve-jobs-do-trump

I get where she’s coming from–the technology industry doesn’t seem to know its own power yet, and it may come from the kind of people running it. Something tells me they still think of themselves simply as much richer versions of the high school kids in Freeway America that they once were. Maybe being at the head of an industry that’s already changed the world is as far as their aspirations go and they can’t bring themselves (yet?) to think of being capable of actually exerting real political power, much less actually doing it.

Kara Swisher at Recode is not so sure:

http://www.recode.net/2017/1/23/14340518/what-would-steve-jobs-do-trump

I get where she’s coming from–the technology industry doesn’t seem to know its own power yet, and it may come from the kind of people running it. Something tells me they still think of themselves simply as much richer versions of the high school kids in Freeway America that they once were. Maybe being at the head of an industry that’s already changed the world is as far as their aspirations go and they can’t bring themselves (yet?) to think of being capable of actually exerting real political power, much less actually doing it.

Interesting writing as always Dana! Miss your input on Seeking Alpha …

-jmac

Interesting writing as always Dana! Miss your input on Seeking Alpha …

-jmac