The wind that for a generation was blowing from the right now blows from the left.

Whether you’re talking about Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, Labour in England, the Pope in Rome or Democrats in the U.S., ordinary people have grown tired of conflict, tired of feudalism, and tired of excuses for prosperity failing to improve their lives while elites play zero-sum games in order to grab more-and-more power.

This wave has been building for a long time and it’s based on an economic fact. The age of oil is ending. The age of technology is here.

For technology to fulfill its potential takes an enormous amount of cooperation. Technology flattens hierarchies, and broadens bases. Technology demands liberty.

I have made my living covering technology since 1982. These trends are not new. What is new is that technology is now at the center of everything. It’s how we move money, it’s how we do science and art, it’s essential to participation in the modern world.

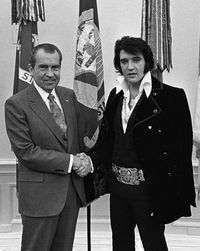

Barack Obama, like Richard Nixon and Franklin D. Roosevelt, was a crisis President. America was capsizing as he approached his inauguration. There was a sense the whole boat could go under. He righted the ship with a liberal program, a $1 trillion economic stimulus whose impact is still being felt. America, alone among the major powers, stepped up to the plate when everyone else was selling and said “buy.” Through that action America’s global economic leadership was renewed.

Economists have forgotten that policy makers have multiple levers for controlling events. Both are limited. The use of both can be overdone, and in both directions. Monetary policy can be too restrictive, and it can be too easy. Fiscal policy can be too restrictive and it can be too easy.

Since passage of the 2009 stimulus, politicians around the world have forgotten another very important truth. Debt is an asset. When you put debt on a bank’s books, that’s an asset. Deposits are liabilities. And governments aren’t families, nor are they businesses. Governments are banks.

In a technological age, growth assets are shared. The Internet is a growth asset. It isn’t “owned” like a railroad or a cable network is. It’s shared among a large number of entities, and it’s based entirely on voluntary agreements, the movement of traffic prioritized over nearly everything else, including content and costs. Other growth assets – roads, airports, seaports, health care and education systems – are also held by networks of people, public and private, who must voluntarily agree on standards of meaning in order for the systems to work.

Thus there is a new political reality, and a new political majority. Cooperation, even consensus, is the political order of the day, because cooperation is needed to make the new economy go. Liberty is the political order of the day, because enormous amounts of brainpower are needed to drive the economy forward, and that only comes from free, educated, and freely educated minds.

But it must be activated.

Nixon talked about a “silent majority,” and what he meant by that was that his voters weren’t easily activated, that they were generally passive, and that they often failed to show up at the polls. There is a “silent majority” active now. People didn’t show up to vote in 2010, and they didn’t show up in 2014, and they’re paying for it in the form of policies they don’t like, policies that don’t work, and politicians who show contempt for whole groups of people – black people, brown people, women, government employees – who represent the majority of their electorates.

This contempt is a good thing. It gets people mad. It gets them active. It drives them to register to vote. It drives them to the polls. It causes them to build coalitions, emotional attachments to people and organizations they see as representing their views.

This majority is centered where the new economy is centered. The new economy is based upon research, usually done in big cities, but it also exists in smaller cities as well, often called university towns. Austin, Texas is nothing like the counties around it, and neither is Athens, Georgia. Neither is Lincoln, Nebraska or Ann Arbor, Michigan. In the near term, these majorities can be gerrymandered, arranged in such a way that their share of the vote isn’t reflected in legislatures. But that only makes the majorities larger.

That’s how it will play out. The technology industries demand cooperation in place of the Manichean competition of the oil era. Technology demands relativism, diversity, and mass acceptance of very broad community norms so that no one’s potential contribution to progress is easily ignored.

Money drives the train. Technology will get what it wants.