Think of this as Volume 18, Number 8 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

To those with a Clue, these seeds are easy to see. It was easy for me to see the growing Internet bubble in the late 1990s, and soon after I launched a-clue.com I began warning of it, sometimes stridently, amazed that everyone around me on the Internet Commerce beat was ignoring it.

The same thing was true for the last recession. There were many voices shouting from the economic rooftops that there was a bubble in housing prices, that liar loans carried risks, and that the “insurance” being purchased against default wasn't worth the paper it was printed on. These voices were ignored as well.

There are two reasons for this.

Still, recessions happen. Once, during the 1980s, it was felt that recessions could no longer happen, because technology was bridging the gap between supply and demand. Net warehouse space devoting to holding goods for retailers peaked in the early 1980s, thanks to bar code readers and mass computerization. The lag between slowing sales and slowing production could thus be predicted, demand and supply could be evened out, and the cause of all recessions from World War II on ended.

What we've found since, of course, is that it's not that simple. War caused George H.W. Bush to press on the economic accelerator in the run-up to the first Gulf War, and once that was won imbalances were inevitable. The Internet economy couldn't just stop – it had to be brought to a halt. Banks felt powerless to stop making bad loans during the housing bubble, fearing a loss of market share.

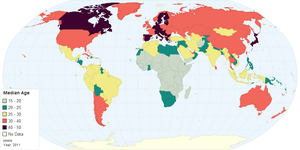

What's going to happen, probably around 2017, are two things. Renewable fuel costs will fall below the cost of oil production, causing a collapse in prices and enormous dislocation. At the same time, the present over-supply of labor will become a chronic labor shortage, as the world faces its aging and my generation retires en masse.

Both these trends are great in the long run, but in the short run they cause enormous economic dislocation, and it's from such dislocations that recessions are created.

But there are two limits to how much people will pay for any commodity, even energy. One limit is supply – when there is too much of something its price goes down. The other is demand – once demand is satisfied there is downward pressure on the price.

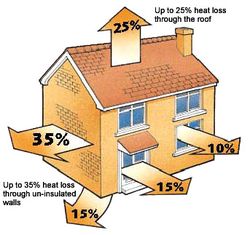

The Sun shines, the wind blows, the crops grow, and we live on a molten rock. Once we learn how to harvest renewable sources of energy, we keep harvesting them. The harvesters naturally depreciate, and the economics just get better-and-better. The insulation you installed in your attic five years ago works just as well today, and will work as well five years from now. The same is true for your more gas-efficient car, your new furnace, and that string of LED lights you bought to celebrate Christmas with.

What these innovations, and others happening every day, promise is a permanent thumb down on energy costs. If it's costing you, say, $70/barrel to dig bitumen out of Alberta and turn it into a slurry, combined with natural gas liquids, which you want to pump down to the Gulf Coast for refining into finished product, those numbers may not work after 2017. At minimum, the margins will become thin enough, and alternatives obvious enough, that the externalities of that production – the destruction of air and water it causes – will come to be factored in.

You will be out of business.

Once it's realized that the value of oil in the ground is not limitless, once the value of reserves are recalculated based on energy abundance, all economic hell is going to break loose. There will no longer be an incentive to control production. Hard choices will have to be made. All this will create a recession. Just as in the early 1980s.

Plus, these median ages are increasing. The population bomb has been defused, but in its place is a global population that is aging rapidly. We can see this most clearly in our own labor participation rate, which is now at a level not seen since 1978, when I first joined the labor force full-time.

That's why unemployment rates keep falling despite slow economic growth – we're all getting older. That's not going to change. At some point workers are going to recognize their increased bargaining power and react, creating wage pressures that automation won't be able to dispel.

But not all recessions are created equal. A crisis recession, like the one which hit in 2008, can represent the end of long-term trends that seem impossible to turn around – in this case energy limits. The same thing happened with manufacturing in the late 1960s, with consumer demand in the 1930s, and with industrial inputs in the 1890s. Economic crises created new abundance in all these eras, and it has done the same in our own.

What comes next will be a recession of opportunity, with enormous incentives for automation of all kinds, and with higher value for anyone willing and able to work. Pressure will build on the top of the economic pyramid – economic pressure rather than political pressure. Stock prices will fall, especially in energy companies and those that depend on large supplies of cheap labor.

But on the other side of that horizon lies a truly wonderful future for our children. There will be challenges. They have to save the planet from our generation's rapaciousness. But they will have the tools to do it.