Despite a lot of rhetoric, and some government action, the forces of copyright absolutism remain in a long, slow retreat.

The alliance to kill webcasting, in which radio broadcasters married themselves to music companies, seems to be coming apart. CNN and The New York Times are retreating from the paid firewalls, waking up to the idea that lower influence and circulation can’t be made up in incremental revenue.

All these acts have a common theme, the economics of abundance. We don’t need CNN’s videos, or the Times’ writing, or the music companies, for that matter. The idea that sharing music increases CD sales, which was heretical a few years ago, is now proven true. If music isn’t heard inside its shrink wrap it doesn’t exist. Yet a purchased song can be heard hundreds of times without becoming stale in a collection.

The same is not true for video, of course. We have a better memory for movies than for the written word, and a lower tolerance of repetition than for music. Some of my favorite movies, like The Americanization of Emily, I’ve seen barely a half-dozen times, yet I can recite whole scenes from memory. Unless the price is super-cheap most people find that buying a DVD is a bad economic deal.

For the written word it’s even worse. The incremental value of

words, whether printed or displayed on a screen, is really no more than

the value you can get for advertising next to them. Books quickly

become worthless, magazines and newspapers quickly become recycling. I seldom read a book more than once.

It’s in finding material where economic value lies. That’s what all

the hot sites of the moment are about, finding Web pages, finding

music, finding movies. Whether we’re writing blog posts, trying to

figure out our own lives or just looking for a good time, it’s in

helping people find what we’re looking for where economic value lies.

These are the intermediaries, the folks who represent us, rather than

the stores or labels which represent the producers.

This is the real reason why the copyright industries are now lobbying for an eternal copyright. They don’t see big bucks in the short term, or even the medium term. The hope is that, by stifling innovation in the long term, by placing a tax on the future (no mash-ups of anything, pay the studio for using that picture of Stan Laurel) they can earn back in the long term what they know they can’t earn in the short term.

But that won’t work, any more than a strict patent regime where software companies spend half their money hiring lawyers to buy rights to what the coders have just written makes sense. You can impose all the taxes on the future you want. In the end the future won’t pay.

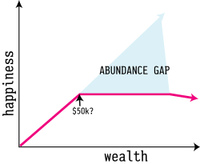

The central dilemma of our time remains, the economics of abundance married to the costs of scarcity.