The following is a work of fiction. Here is the Table of Contents, which is updated as new chapters are written.

It is the third in a series of sci-fi novels of the type known as

alternate history. What’s different is that this series takes place in

our time, with characters familiar in your real life.

The first book in the series, The Chinese Century, was written late 2004. Its table of contents is here. The second, The American Diaspora, was written in 2005. The table of contents for that book is here.

It’s boring.

It’s all meetings. Meetings about marketing. Meetings about finance. Meetings about hiring. Meetings about where to site a production facility. Meetings with local politicians near the site we chose. Meetings with local politicians at every site we didn’t choose. Meetings about science. Meetings about public relations. Meetings about accounting. Meetings about meetings.

No time for reading. No time for writing. No time for family. No time at all.

My secretary gets me a Blackberry and locks me into the alarm function. I think it’s going off every 5 minutes. Sometimes it is.

The drumbeat is constant. No more time for a nice morning workout. Wake up at 6. Go full-out until 10 that night. Then go through the paperwork. It’s absolutely unrelenting. In a year I’ll look like Sydney Greenstreet.

Worse, I don’t know if I’m helping. I can criticize what others are doing. Bounce things off me and I can bounce them back. But strategize? Budget? Project? I can look at a financial report that has been handed to me, turn to the last page and guess what’s going on. But now I have to watch one getting built, and it is driving me crazy.

I would love to talk to Mark Cuban about this. I would love to talk to Branson. I can’t get near either one – they’re either out of town or booked more solidly than I am.

You know what is really strange? I’m not the person in charge of my own life any more. That’s the secretary’s job. She came directly off Branson’s staff, and she’s very, very good. But she’s also horribly, horribly controlling.

So when the alarm goes off at 2:15 one day, and I rush between my "public" office to my "private" one after inelegantly taking my leave of a delegation from Soweto, I barely have time to glance at the Blackberry and read the name, "Chris Gardner."

It means nothing to me.

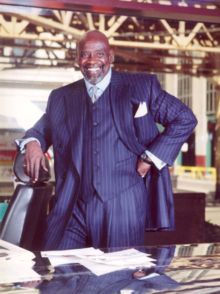

The black man whose hand I shake is tall, mature, well-tailored, elegant in every way. His soft voice has a natural American accent, and I soon learn he’s from Chicago, that he came here three years ago, inspired by Nelson Mandela to create jobs for South Africans after selling his own little investment bank.

"So how’s that going?" I ask.

Not so well, he says. And he then proceeds to sketch out a story, about South Africa’s over-dependence on minerals, about the difficulties in training young men, about the impossibility of recruiting young women. He describes the social structure of ghettoes, about how little education is required to change those structures. He talks about religion, he talks about God. He talks about Mandela, whom I’ve seen but never conversed with, and I’m carried away by his vision. He is charismatic like no one I know, besides Branson.

The buzzer in my pocket sounds. Reluctantly I pull out the Blackberry. I’ve missed two other appointments. I don’t believe it.

"Come with me," I say impetuously, a little imploringly.

Gardner and I return across the wall to see my 2:30. I introduce Gardner as an associate. He apologizes for me, shakes hands all around, speaks for just 15 seconds, and the group leaves, satisfied. He mutters to my secretary, who brings a second group through, right past the first one.

In five minutes we’re alone again.

Then Gardner talks about himself. He talks about his rise at Dean Witter, about his son Chris Jr., now at Witswaterand. He talks about the unpaid internship he did in 1982, about sleeping with his son in subways, about the lessons it taught him, and about the responsibility he feels in his life.

"You should be a movie," I joke.

He laughs. "We were close, before the 2004 election," he says quietly. "Will Smith had taken an option. We were talking about who might direct. Then the new production code came in and everything collapsed.

"I would like to see a movie like that. But only if it’s done world-class. That’s what South Africa needs, world-class companies, world-class culture. America may fall but others will rise. Africa will rise."

I believe him. This is what leadership looks like. I’ve just been playing at it.

"What was the subject of our meeting to be?" I ask finally.

"Branson sent me. He said you could use some help."

I smile. "Yes. Chris, would you like my job?"

His smile then is like the Sun coming up. With his pat on my back I feel the weight of the world lifting off my shoulders.

Tonight Jenni and will celebrate. I have fired myself, and I couldn’t be happier.