Following is the essay you can designate as Volume 10, Number 35 of

This Week’s Clue, based on the e-mail newsletter I have produced since

March, 1997. It would be the issue of September 3.

Enjoy.

The key to how technology has changed, and how politics

has changed, is the same as how our approach

to energy must change.

Technology is no longer defined by the few, but by the many. Computing power is no longer centralized, but decentralized. The greatest use of spectrum comes from unlicensed frequencies, not licensed ones. The best network is a dumb one, defined at the edge rather than the center. The big money in politics should come from the netroots, not the big contributors.

Open source. The Internet. WiFi. Howard Dean. Blogs. They’re all telling us the same thing.

Our approach to the War Against Oil is completely wrong.

We’re focused on defining point sources, on big plants. On corporate or government control. We should be focused on decentralized systems, defined at their edge. They’re more robust, they’re more defensible against attack by guerillas, but more important they work.

Yet the proprietary centralized model is the only one we read about. That’s because, in the oil era, this defined the only correct approach. Oil and coal aren’t everywhere. The process of cracking petroleum to produce useful fuels is dirty and dangerous. Tesla beat Edison.

With new times, new sources, and new problems should come new approaches.

Where does the new energy come from? It comes from the Sun, it comes

from the wind, it comes from the Earth. These sources are largely

untapped, and they exist nearly everywhere. There is far more wind

energy blowing through metropolitan Atlanta right now than there is at

the top of Brasstown Bald, Georgia’s highest mountain. And there is

just as much solar radiation shining on downtown Phoenix as there is an

equivalent amount of desert. While geothermal energy is more easily

reached in the western part of the U.S. than in the east, there is

still plenty when you drill deep enough.

The best way to tap this immense energy store is at the edge, not

the center. That means we need standards for solar panels, for

connectors, for connections to the network, and for residential

windmills. We also need to think of the electrical grid’s design as

being akin to that of the Internet, not to 19th century grid we use

now.

Then we need to let Moore’s Law do its thing.

Let’s start with solar panels and windmills. Think of the new

standards as the 802.11a standards of this new world. The first 802.11

standard, passed in 1997, defined 1 million bits/second of bandwidth

using unlicensed frequencies. The next standard, 802.11b, defined 10

Mbps. Today’s standard, 802.11n, moves data at 100 Mbps. Using the same

power. Using the same spectrum.

I don’t expect the same types of improvement in solar or wind,

because the way we produce power from solar panels is not so clearly

defined as silicon production is. Yes, you can make solar panels the

way you make silicon chips. But there are other methods as well. Each

has its advantages. We need competition here.

The result will be the same — multiple generations of equipment,

each better than the one before, each worth the price of the upgrade.

If, that is, the underlying technology is similar enough that you don’t

have to rip everything out in order to put something new in.

The same approach can work with wind. We need to define the size of

an unobtrusive, residential windmill. How high can it be, and how big

can the blades be? Once we have that definition down, let competition

reign. Tomorrow’s windmills will be better than today’s. They will turn

wind energy into electricity more efficiently than what we can today,

and they will capture more wind energy as well. If we define standards,

we can buy the upgrades on our pace.

The second problem is the grid.

Right now, our electrical system is run like a 1970s cable system.

It’s a one-way conduit. You can reduce the amount of electricity you

buy from the system, but you can’t sell juice back at the price paid.

The system just isn’t equipped to handle it, nor is it equipped to

account for it.

One reason the power companies don’t want to make this investment is

they wonder what happens as local supplies increase. Electricity isn’t

like other resources. It’s either available at the designated wattage

and power, or it’s not. And it has to be carefully measured, stepped-up

and stepped-down, to stay useful.

It’s a big job to go from delivering power to managing power

exchanges, and the electrical companies must wonder, what do you do

with the excess?

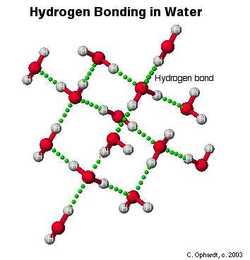

The answer to that question is hydrogen. Use excess electricity to

produce hydrogen for use in fuel cells. That supply will stimulate

demand in transportation, whether the fuel is used ultimately as

hydrogen, as ammonia, or as something else entirely. (We don’t know the

right answer to hydrogen storage-and-use in transportation. Supply is

needed to create demand for those solutions.) The waste from a hydrogen energy cycle, also remember, is the answer to our water problems.

As a result of reticence on the part of the grid monopolists

most of the electricity substitution you’re seeing is on the margins.

You don’t have to buy a watch battery if your watch has a tiny solar

cell. You can buy security lights for your walk which have their own

solar panels in them, storing energy by day which they release as light

at night. If you’re lost on a freeway at night and find an emergency

phone, that’s likely solar powered as well. We’re also seeing the

emergence of solar-powered signs.

None of this connects to the grid. The grid is stupid. The grid is

inefficient. The grid is where we need to be putting money. The owners

of the grid must be induced to pony-up for this, at the risk of being

broken up or given competition. Throwing tax credits at them will be

useless, just as throwing tax credits to phone companies for broadband

over the last 10 years was useless.

Winning the War Against Oil requires that we think in new

ways about energy, its production and its distribution. Fortunately we

have a model for such thinking.

You’re using it.

I agree that this is the right approach, but it will take a lot of regulation at many levels government.

At the federal level: Utility companies must be forced to adopt a single standard for a 2-way grid and adopt is by some reasonable date, let’s say 2020 (I’d like it to be sooner, but these things always take at least 10 years). Then there needs to be some sort of zoning over-ride that specifies types of personal power generation gear that must always be allowed. Having these three things is the only way to actually have a framework where anyone can install the type gear you envision driving the edge model.

At the state and local level:

PUC and franchise guidelines must mandate that electric utilities give equal consideration to buying personally produced power as they do with power produced from any other source. Basically, a unified rate structure is required. Otherwise, in many cases utilities will just refuse to buy power back from their customers or at least refuse to pay competitive rates.

I agree that this is the right approach, but it will take a lot of regulation at many levels government.

At the federal level: Utility companies must be forced to adopt a single standard for a 2-way grid and adopt is by some reasonable date, let’s say 2020 (I’d like it to be sooner, but these things always take at least 10 years). Then there needs to be some sort of zoning over-ride that specifies types of personal power generation gear that must always be allowed. Having these three things is the only way to actually have a framework where anyone can install the type gear you envision driving the edge model.

At the state and local level:

PUC and franchise guidelines must mandate that electric utilities give equal consideration to buying personally produced power as they do with power produced from any other source. Basically, a unified rate structure is required. Otherwise, in many cases utilities will just refuse to buy power back from their customers or at least refuse to pay competitive rates.