The following is a work of fiction. Here is the Table of Contents, which is updated as new chapters are written.

The Duke of Oil is the third in a series of sci-fi novels of the type known as

alternate history. What’s different is that this series takes place in

our time, with characters familiar in your real life.

The first book in the series, The Chinese Century, was written late 2004. Its table of contents is here. The second, The American Diaspora, was written in 2005. The table of contents for that book is here.

A synopsis of the series is here.

As far as I was concerned Chris Gardner had already earned his salary.

We really just had some prototypes of Wong’s new solar panels. The connectors and other hardware came from a local hardware store, standard and cheap. Gardner added a GE hydrolyzer along with a collecting hose-and-tank for the oxygen produced by the process.

It looked like a kludge, but Gardner put the whole thing in two boxes, put the boxes into a truck with a logo, and made a few phone calls.

Two days later we’re in Qunu, in the Transkei, a tiny collection of buildings dominated by a large dirt-colored house, surrounded by two fences. We were a half-mile from that house, on the roof of a dun-colored building that acted as a local government office and civic center.

I was supposed to be supervising the engineers installing the system, which included running a hose from a water pipe and a pump to the roof. But the guys were having no problems so I slipped down the ladder and went inside.

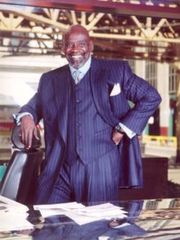

The village elder sat behind a cheap Chinese table, in a high-backed wooden chair. Gardner had abandoned the small chair on his opposite side, and was busy explaining the papers before the man, his hands waving in the air, casting a salesman’s spell. Gardner wore a linen jacket with a white dress shirt, no tie, matching slacks, and black shoes. The elder wore an open-necked white shirt.

"This is our model contract," Gardner said. "We want a model we can sell to thousands of other villages, throughout the counry.

“You pay no money down for the installation. You pay us in gas, in oxygen and hydrogen, which we’ll collect weekly for now but eventually collect automatically, perhaps through a pipeline, perhaps using balloons. The remaining electricity is yours to use, to sell, to act as back-up power, to run homes and businesses through your village utility.

"We estimate you can pay back the cost of this system in 24 months. After that, all the electricity it produces goes to you, along with the gas, and the water you collect from using the gas. If you use more of the electricity locally, it will cost more, and we’ll examine the figures at the end of the 24-month term to see where we stand. That’s the nature of a pilot program.

"It’s green power for you, free power to build your community."

"And for you?" the elder asked.

I saw Gardner smile. Questions are always an opportunity, he told me when he first took over. "The gas you’re producing has value. We can account for that value. We can make a market for the gas. No doubt it will be expensive for us to collect and market the gas early in the contract.

"We may build a pipeline. We may turn it into ammonia and transport it in tanker trucks. We may turn it into fertilizer we can sell. We may put it in balloons and fly it to Johannesburg. Eventually we want you to be able to re-sell it, right here, for use in fuel cells. The fuel cells will make water, the water can be used to make more gas, all based on the energy of the Sun. This will grow the market and increase demand for the panels as we produce more of them."

I saw the elder frown. Gardner sensed his chance, pulled a pen from his jacket, handed it to the elder. The elder grunted, looked up at Gardner, and signed. Smiles, a handshake.

I couldn’t have done it. During the exchange my palms were sweating, my heart was pounding. I knew we couldn’t just take the stuff away, and I also knew that we couldn’t make this work in just any Transkei village. We had to have this sale. Gardner’s high-wire act with the village elder just had to work.

The reason for that was living in the dirt-colored house a half-mile away. The old man living there was no ordinary old man. It was Nelson Mandela. I knew that, Gardner knew that, and the village elder knew that. He wouldn’t be doing this unless Mandela, and his people, had already seen what Gardner was offering and, in some way, endorsed it. In fact, Gardner had faxed the papers to Mandela himself, and briefed him via teleconference.

So yes, this was something of a kabuki. But that didn’t make it any less real. Had the elder held out for more, had he demanded something Gardner couldn’t deliver to other villages, his plan might have stopped right here, in this small office in Qunu.

Now it would start instead.

Gardner’s knowledge of process, of details, of salesmanship, and of theater awed me. I had covered men like this all my life, and it always amazed me, how they kept their nerve. Adrenaline tended to turn me into a sweaty puddle, but for these men it was like cocaine. It energized them, and I knew from experience it left them limp afterward. Tired, and wanting to do it again.

I stepped back into the hallway, let Gardner and the elder pass me by, without demanding any acknowledgement. A tent had been erected just outside the main door, one of those asnings kids’ soccer teams use to keep cool during games.

A bus pulled up on the other side of the awning, and an enormous collecion of reporters, with their gear, piled out of it. I peered past the horde, at the bus driver.

From behind the wheel, Richard Branson waved.