Following is the essay you can designate as Volume 10, Number 36 of

This Week’s Clue, based on the e-mail newsletter I have produced since

March, 1997. It would be the issue of September 10.

Enjoy.

The Internet is naturally resilient.

When a direct path to a bit’s destination is blocked, it automatically goes around the blockage. This is a critical design feature. It may be the most under-appreciated aspect of the whole network.

Dave Isenberg calls this the "stupid network" because it’s controlled at the edge, not the center. This makes censorship difficult. But it does more than that. It makes the whole network efficient, even more efficient as it grows.

Unlike the traditional telephone network design which preceded it, where whole cities might become dependent on a single switch, a single point of failure, the stupid network scales. It becomes more resilient as it grows, not less resilient.

The same principle has been applied to politics in this decade.

Four years ago I was a small part of the Howard Dean campaign. I criticized that campaign of failing to "scale the intimacy"

as its membership passed the 1 million mark. At the time I was thinking

only of how much better a Community Network Service like Drupal would be than a blogging system like Movable Type.

History shows I was right. Simply by scaling in this way, the Democratic Party was transformed over the next few years.

The campaign of Barack Obama tried to answer my criticism this year

by building out a host of services, all scaled to fit the enormous

traffic a national campaign would generate. During the spring this

worked. Now it’s not working as well. Growth in Obama’s networks has stalled.

I don’t think this is all down to Obama’s message. I think it comes

down to a key design decision the Obama campaign made months ago, which

was to bring all its messaging in-house.

The campaign was seeking greater control of its message. Critics may

say this made the Obama site an echo chamber, less fun to go to. But I

think the fault lies deeper. I think it’s architectural.

By contrast to the Obama campaign the liberal blogosphere as a whole

continues to rocket ahead, because it is highly resilient. The liberal

blogosphere consists of thousands of sites. Some are as popular as

cable stations. Others are as niche as newsletters. Some cover the

nation, others a state, still others a single town. Most of the biggest

are now group efforts, often built around an almost-unspoken theme.

Fame. Feminism. Policy. Process.

The biggest challenge for this growing blogosphere lies in keeping

stories flowing from the bottom-up. One way to do this, I find, is

through a 50-state strategy. Liberal blogs in each state

read local blogs within those states, link to them, build them up, and

these stories in turn are passed upward to the national sites. This

enables local bloggers to be heard, to be validated so they will

continue to work. It also makes the liberal blogosphere more resilient.

I contrast this with the way the conservative blogosphere works.

Stories there flow from the top-down, either from campaigns or national

sites down into the grassroots, which act as local echo chambers. At a

recent conference conservatives promised to "get it" about this

process, but there is no evidence this is in their DNA. The result is

that the conservative blogosphere is brittle.

I see this all the time at Voic.Us, the news site I have worked on for the last two years.

- In Virginia,

struggles which were important to conservatives like Prince William

County’s war on illegal aliens, or the alleged harassment of a group of

bloggers by a Democratic operative, went unnoticed in the wider world. - In North Carolina,

efforts which were important to liberals, like the battle against an

Outlying Landing Field in the east or a new diesel-fired power plant

near Asheville, were picked up and amplified by state blogs. They

became statewide issues. And the Democrats won both fights.

Political network design, in other words, is not just a technical

issue. It is very much a human issue, an organizational issue, a

management issue. A resilient movement which moves stories up the tree

is going to beat a brittle movement which either pushes stories from

the top or keeps things closed at the center.

This is a vital point in regards the War Against Terror.

Over at Global Guerillas, John Robb says that a resilient design

is the best way to beat terrorism. He calls for a resilient society and

resilient enterprises, one in which every citizen is ready in case of

emergency, in which every business is as self-sufficient as possible,

and in which the infrastructure is designed with resilience in mind.

This is also a vital issue as we approach The War Against Oil.

Our present electrical network is not resilient at all. It is a

one-way network in which electricity is produced entirely in large

plants, far from the cities, then moved over high-power lines to

transformers, where it’s stepped down for use. In my neighborhood I

still must have my meter read every month by a guy who walks the

streets with a pad of paper.

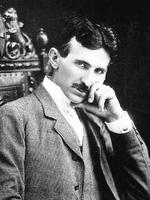

This made a lot of sense in the 19th century. Nicola Tesla’s ideas

about A/C current, which made the present electrical network design

possible, triumphed over

Thomas Edison’s ideas concerning a D/C network. While Edison built a

power plant in J.P. Morgan’s basement, Tesla was able to have scaled

power plants deliver clean, reliable power to entire cities.

This made a lot of sense in the 19th century. It makes less sense

today. Yet we’re still thinking in ways Tesla would be familiar with,

not Edison.

Even the grandest alternative energy visions have distant power

plants producing vast quantities of energy which must be transported,

by truck, by pipeline, or by wire, to the cities. Right now we lose

half of every kilowatt we transfer in this way — due to the resistance

in the "conducting" wires of the grid. It is possible to increase the

capacity of every power plant by simply improving the wires, and some

of that work is already being done.

But there is something else we can do.

We can produce our own power. We can put solar panels on our homes,

lots of them. We can put windmills on our lawns, lots of them. Each of

us won’t make a lot of power, but there will be times — when it’s

windy, when the Sun shines brightly, when we’re off at work — when

we’ll be producing more than we need.

How can we use this power? The answer, as Al Gore has noted, is for

the electrical grid to take that power, to bank it, to pay for it, and

to re-sell it. He calls it an "ElectricNet," but it’s really just a two-way electrical network, with some intelligence built into it.

More important, it’s resilient.

Even more important, it encourages utilities to find ways to "bank"

excess power, in the form of hydrogen. When you’re taking in more power

than you need in a particular area, you use hydrolysis on water to turn

some of that power into hydrogen and oxygen gas. Put these together and

you have rocket fuel. Combine the hydrogen with nitrogen and you have

ammonia, or fertilizer. Bottle the hydrogen, stick it in a fuel cell,

and you’re running cars or trucks without gas, with water as the

"pollution." Save the water, and your water supply is now produced

closer to your water demand.

Resilience.

A resilient electrical network can not only buy power from

consumers, businesses, and landlords, it can contract with

entrepreneurs for other types of power. It is no longer dependent on

the utility for supply.

Geothermal power, for instance, should be produced in the

countryside, and there’s a lot more of it closer to the surface in the

U.S. west than the U.S. east. But a resilient electrical network which

can bank this power in the form of hydrogen would allow entrepreneurs

to tap this power efficiently.

The same design concept which makes the Internet powerful, which

makes the liberal blogosphere powerful, can be harnessed to win the War

Against Terror as well as the War Against Oil.

And that’s the direction we need to head toward.