When we think of Gerald Ford today, we think of the late former President with fondness.

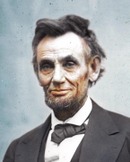

We don’t think of what he was in 1967. (That’s him to the right. Notice who is applauding him.)

In 1967 Ford was the House Minority Leader. He was a good foot soldier for the cause, albeit a bit stolid. Few people by that time remembered the Michigan center or the male model. He was the gentleman from Grand Rapids, as solid a Republican seat as you could have, comfortable in his own skin and comfortable in Washington, D.C. (This is not an easy trick.)

With the 1966 election in their rear-view mirror, conservatives felt they had, if not a real majority, at least a working majority on a host of issues. By combining the votes of southern Democrats with their own Republican troops, movement conservatives felt, they could at least stop Democratic advances, the War on Poverty, the Great Society, the Civil Rights laws.

But they couldn’t. Somehow. Liberal justices like Thurgood Marshall were confirmed. Deficit-laden budgets offering both guns and butter were passed with ease. Ford, conservatives felt, was one of the chief enablers.

He was. By 1967 he had been in the House for nearly 20 years. He had been a member of the majority for just two of those years, under Speaker Joe Martin. Martin’s majority was killed in the anti-McCarthy election of 1954, and Ford learned a lesson from that. Don’t challenge Democrats directly. Lean against their assumptions. Moderate them. Be the anti-thesis. It worked for Eisenhower, and Ford became loyal to Eisenhower’s vice president, Richard Nixon.

So who’s Gerald Ford now?

Like Ford, Rahm Emanuel is an anti-thesis politician.

While Ford leaned against the Roosevelt Thesis, learning from the 1954 debacle not to question the myths and values of the New Deal, Emanuel grew up under the Nixon Thesis, learning from the 1994 Republican Revolution not to lean too hard against it.

And while Ford was distant from his party’s defeat, a low-ranking House member, Emanuel had a front-row seat as a domestic adviser to President Clinton.

Clinton, like Eisenhower, had much of his idealism emasculated by his mid-term defeat. Both Clinton and Eisenhower spent the rest of their time in office seeking only to moderate the assumptions of their time. Both hoped to gain credit for this moderation, and both were surprised when their Vice Presidents were defeated. When you lean against a set of political myths and values your victories, paradoxically, help validate them.

Emanuel himself was only elected to Congress in 2002, yet quickly rose to a leadership position due to his partisan nature and his fund-raising ability. But partisanship, in the sense of loyalty to a party, is not the same as partisanship, loyalty to a set of principles.

Rahm Emanual, like Gerald Ford, is a party partisan, not a partisan on behalf of principle.

And this is what Netroots Democrats find so annoying about Emanuel, just as movement conservatives 40 years ago were angry with Ford. He is perfectly willing to sell out on issues if he thinks it will advance his party’s cause in Washington and New York, where he believes real power lies.

Trouble is, at a time of crisis, New York and Washington are not where power lies. In times of crisis power rests with the people, those who are changing their minds, and those whose minds have already changed. The time of a crisis is filled with potential political energy, and what appears true in New York or Washington is merely the wind that doesn’t blow.

Emanuel, like Ford, is leaning into a wind that no longer blows. Ford got lucky. He tied himself to a crook and wound up with a life of glory and fame.

Don’t bet on Hillary’s impeachment, Rahm.

check out that cool new ford book ford and the american dream by clifton lambreth its a great read

check out that cool new ford book ford and the american dream by clifton lambreth its a great read