I was out last week, saying goodbye to

a Great Man. .

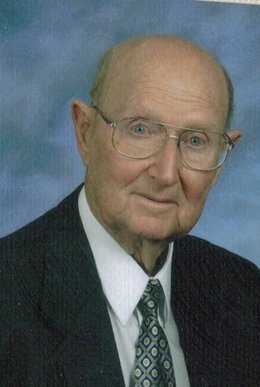

Bennie F. Steinhauser (right) was my

father-in-law. We drove 2,100 miles over 5 days for his funeral.

He could be intimidating,

without trying to be. When I first met him, in the mid-1970s, he was at the

height of his power. He was a veteran school superintendent. He lived

in a great house he’d designed himself. He was constantly moving

among his ranches and his factory. He presided over Sunday suppers

for an enormous extended family that included third cousins.

I was there to steal his

baby.

He didn’t much take to me.

I was a scruffy, bearded college student whose sole ambition was to

work at a newspaper. His baby, whom I called Jenni, was an honor

student, a space science major, maybe a future Astronaut. She was

beautiful, talented, and brilliant. Still is.

So I could never bring

myself call him Bennie, even after he asked. It was always Mr.

Steinhauser. Maybe, had I had known the other Bennie F. Steinhausers,

the ones in his autobiography “Never Alone” (which I insisted on

not writing), I might have felt closer.

-

I didn’t know the

child who rode to school on a horse, 6 miles each way, whose first

language was German, the practical joker who tutored the football

players and became the first in his family to graduate high school. -

I didn’t know the

handsome young man who courted the niece of his landlady, who worked

at a five-and-dime, and who published his wedding vows in the

newspaper of December 7, 1941. -

I didn’t know the

soldier, the interpreter and aide, who packed a bicycle into a

filing cabinet so he could pedal around occupied Germany, and whose

combat experience consisted of keeping a fellow G.I. from raping a

12-year old. Decked him with one swing. -

I didn’t know the

young go-getter who ran stores for S.S. Kress, or who went to

college at night, to build a better life for his young family. -

I didn’t know the man

who rose, in just a few years, from classroom teacher to head of

Texas’ 4th largest school district, and its 2nd-poorest. -

I didn’t know the

politician who won aid for that district, for mostly-Hispanic

children, based on their need and proximity to an Air Force base,

who named his first schools for big politicians like Harry S.

Truman, and got them to show up. -

I didn’t know the

kind-hearted man who finally asked his kids what they wanted a

school to be named, then threatened to “name it after Bing Crosby”

until Bob Hope called back with a date for its dedication. (Hope

called it his greatest honor, and meant it.) Whenhis school boardhe resigned his first job, after 13 years, it was front-page news, and he had an

canned him

identical job minutes away within afew months.fairly short time. Unlike 99.99% of other school superintendents, he never had to move for work.

All I knew in 1975 was

what Bennie F. Steinhauser had become, a human dynamo, the

paterfamilias, the education leader, the man everyone looked up to.

Of course I had a secret

weapon. I knew his secret, his single flaw, his dark shame.

Jenni told it to me.

He wasn’t home. “He went

out before I woke up and got home after I went to sleep,” she

complained. A place would be set for him at dinner, he would promise

to be there, but something would come up. A Great Man’s work is never

done. A full day of crises, often meetings into the night. Or a

crisis at his plant, South Texas Perlite, where he cooked an obscure

mineral until it popped like popcorn, yielding an insulator for roofs

or an aerator for potting soil. Or a family member would have

trouble, or a friend, and Bennie never asked “why me,” he just

acted. If you want something done, ask a busy person.

His wisdom, judgment, tact

and honesty were legendary. If he had old-fashioned values they were

good values, Texas values.

Jenni’s vacations were

hurried affairs, like a long car ride to Alaska. Tossing snowballs in

summer, following the lumber trucks up the Alcan Highway. Seeing new

people, trying new things. For those days he was Daddy. Until a few

days from the end, in South Dakota, when a phone call came, anhe flew away. The rest of the trip passed in silence. (NOTE: Jenni’s mom says his leave-taking was planned.)

emergency. He

So Jenni was mad when I

first knew her. But it passed. She grew up.

And he changed.

His retirement years were

a wonder to behold. They were perfect.

He traveled to every

continent. He became present for everything he’d missed before. He

supported his retired teachers, became an elder in his church, grew

closer than ever to his little brother Otto, often traveling

together, Bennie and Ruth, Otto and Helen. When our daughter Robin

was coming he flew up from San Antonio, and at age 67 he spent

several days building two closets in our bedroom, by hand, sleeping

in the sawdust. When she was born all four of them came up together

in a van, to hold her, to sit at our table, and buy us fried chicken.

He became, in short,

present. For Jenni. For me. For Robin, and for our son John. Present

in fact, as well as in spirit, and financially, too. He gave us the

down payment for this house. He paid Jenni’s tuition. He did similar

things for his other two children, in their times of need, and for

his grandchildren, and his great-grands.

His last trip was to

China, with his son Franklin, who now goes by Ben. They walked the

Great Wall, and climbed the steps of Tibetan temples, the son huffing

in the rarefied air, Bennie joyfully running ahead, a child of 80. He

even built a “doll house” for Ruth on a ranch they owned, just a

half-mile from the refurbished cabin he’d been born in, and grew up

in. Even at 85 he was planting trees, and worrying over their fate.

When the end came, as it

does to all men, he went through all the stages of grief. Only the

immediate family knew of the cancer, the pain of the chemo, how the

cancer came back again-and-again. He was far too young to die.

Finally, around Christmas,

he reached acceptance. He told Ben he had to get out of the hospital,

that he had to get home. “They’re working on the papers,” his son

said. “Papers, I’ll sign the papers. Let me sign them.”

All there was before him

was a Styrofoam food container. So he signed it, in a strong, clear

hand. Bennie F. Steinhauser.

Yet still, he still one

thing to do, one favor to ask of God. He couldn’t die in a hospital.

He couldn’t die alone. Never alone.

So he came home, for the

last time, on December 27, 2007. It was his wedding anniversary, his

66th wedding anniversary. All those relatives who could

be found gathered around him. One by one they went in to talk.

You don’t say goodbye at

such times. You say I love you.

We were in California. For

once, I had decided, we would visit my mother, and my

sister, and my brother. Sorry to say Jenni was alone, at my

sister’s, the next day, when the call came. The end was coming. They

held the phone to his ear. “I love you Daddy,” she said. He was

gone within minutes, and when I returned from errands a few minutes

after that, I took one look at her face and I knew.

So we got home, then drove

to Texas for the Great Man’s funeral. Well, his celebration, for what

else can you call it when a man lives for 88 years, has all the

success and adventure and love a man could ever ask for, when he’s

run his whole race with honor, when he has found peace and seen God.

Jenni wondered if anyone

would show up for the service. At his age, most of his friends should

be dead. But I looked into the parking lot 15 minutes before kick-off

and it was like the last scene in “Field of Dreams.”

People will come.

People came. Hundreds of

people. Some in wheelchairs, some on walkers, some struggling

mightily up the single step to his casket. I sat next to my wife and

was given the tributes. He was my 8th grade teacher. He

gave me my first job. He was my best friend. He saved my life. On and

on it flowed. The pews were filled.

The next day, yesterday,

we buried him in his hometown of Flatonia, in a cemetery close to the

freeway, the river-like sound of life rushing by, near the turn you

take for the Shiner brewery, in a corner plot, where people can visit

easily.

I’m told there’s a place

there for me, too. But instead of going there I will try to become

worthy of him. I will remain true to his daughter, remain present for

his grandchildren, and do all I can to be honest, to work hard, in

honor of his memory.

Perhaps, one day in

heaven, I will see him again. I will shake his hand. I will look him

in the eye. And at last I will call him Bennie.

For clarification purposes only…..

It was his Granddaughter and her thirteen year old son, his Great Grandson, who were at the hospital on December 27th. In fact, it was his Great Grandson that continued to reassure him, throughout the six hour ordeal that he would make it home to ‘GiGi’ for their anniversary. Since our arrival that morning we continued to assure him that the papers were being taken care of and that soon he would get to leave. It was at this time that Grandfather grabbed the Styrofoam box that had previously contained nachos and wrote the most legible signature. Grandfather then put the pen down and said, “I signed the release forms, Let’s Go!” We visited him almost daily and it was apparent that the longer he was in the hospital the more agitated he got. My sons and I, as well as others visited him frequently. As the days passed so did his strength. In the end he had one thing on his mind and in his heart… He wanted to get home and be with the ones who loved him. Jenni may not of been home, yet her presence is always in the house that he built for his family, therefore he wanted to be home with his family, especially Grandmother, and the memories.

In terms of the phone call from Jenni, let’s just say that in her heart she knew that his time was near. As GiGi, my mother and I held his hands and reassured him of our love – Jenni calls. I answer the phone and explain the dire circumstances, I then hang up and call her back on a cordless phone. Jenni knew that his time was near, for she knew exactly when to call. Jenni was able to tell her Daddy goodbye for the last time before he died.

For clarification purposes only…..

It was his Granddaughter and her thirteen year old son, his Great Grandson, who were at the hospital on December 27th. In fact, it was his Great Grandson that continued to reassure him, throughout the six hour ordeal that he would make it home to ‘GiGi’ for their anniversary. Since our arrival that morning we continued to assure him that the papers were being taken care of and that soon he would get to leave. It was at this time that Grandfather grabbed the Styrofoam box that had previously contained nachos and wrote the most legible signature. Grandfather then put the pen down and said, “I signed the release forms, Let’s Go!” We visited him almost daily and it was apparent that the longer he was in the hospital the more agitated he got. My sons and I, as well as others visited him frequently. As the days passed so did his strength. In the end he had one thing on his mind and in his heart… He wanted to get home and be with the ones who loved him. Jenni may not of been home, yet her presence is always in the house that he built for his family, therefore he wanted to be home with his family, especially Grandmother, and the memories.

In terms of the phone call from Jenni, let’s just say that in her heart she knew that his time was near. As GiGi, my mother and I held his hands and reassured him of our love – Jenni calls. I answer the phone and explain the dire circumstances, I then hang up and call her back on a cordless phone. Jenni knew that his time was near, for she knew exactly when to call. Jenni was able to tell her Daddy goodbye for the last time before he died.

Thanks for adding that. Jenni found a few minor points that I got wrong, but let me keep things as they were for dramatic effect.

Our memories of friends, family, of everyone are individual and precious.

Love to you, to Richard, to Ryan and Clint.

Thanks for adding that. Jenni found a few minor points that I got wrong, but let me keep things as they were for dramatic effect.

Our memories of friends, family, of everyone are individual and precious.

Love to you, to Richard, to Ryan and Clint.