Lenny Bruce. Richard Pryor. George Carlin.

The grand tradition of comedy states that the comic himself feels miserable inside, that the words are weapons, and that the energy required for brilliance on a stage exists only with the help of chemical stimulants.

Which chemical seems hardly to matter. For Pryor it was coke, for Carlin pot. For the earlier generation it was booze. Is it possible to be funny without constantly teetering on the edge of self-destruction?

It is. Bill Cosby. In retrospect perhaps even better than Carlin. But in other ways an ordinary man, with an ordinary life, filled with ordinary disasters, like the loss of his son. Such things happen to everyone, can happen to anyone at any time. A great man and a great comic, from the very beginning to this very day.

(Trivia note. Carlin’s original partner was another like that. Jack Burns. Later half of Burns and Schreiber. Still later the first head writer of The Muppet Show. Edited picture from KXOL. My apologies to Mr. Burns, but I promise the other half of the picture when you go. Rim-shot.)

In some ways we’re all teetering on the edge, aren’t we?

The comic I personally admire most is Jerry Seinfeld. Not because of his stuff.

Because I was privileged to watch him develop it, starting at Birch

Lane Elementary School, nearly a half-century ago now. He was a year

older than I was. I was among the many he would later term "school yard

funny," humorous in our way but not serious about it, not studious. I

do wish I’d been more studious about comedy, less serious about what

was happening around me. Maybe I’d be dead by now, too. (Rim-shot.)

Jerry Seinfeld is studious about it. Always has been. He studied the

greats, like Abbott & Costello, as a child, thanks to TV, and was

able to pull their stuff apart, then put it back together, in order

to come up with his own persona, which emerged fully formed as I was

graduating from college. (UPDATE: As always, it’s best to let Jerry himself explain Carlin’s genius.)

Maybe that’s the key. Maybe TV was Jerry’s drug, the secret sauce

that let him develop his own style in private, until it emerged

Athena-like. Imagine that. TV is good for you. If you’re funny.

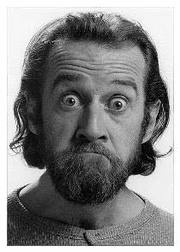

Earlier generations of comics didn’t have TV. Carlin certainly

didn’t. He had to build his own persona up in pieces, under constant

pressure from the market. It’s hard to imagine him in a suit and tie,

clean shaven, but that’s how he started, in the early 1960s, one of

hundreds of Bob Newhart clones wandering the country, trying to be

relaxed, secretly mad inside.

Carlin’s persona, like all the comics which preceded him, developed

under klieg lights, in the harsh glare of reality. What emerged,

finally, was the anger of the 1960s, in all its glory. Fast, heavily

verbal, intensely intellectual, but mostly angry. "Well, we’re all

Nixon’s niggers now," he said on an early album, and the crowd went

wild.

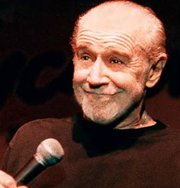

The crowd continued to go wild but Carlin remained a restless soul

until the end, constantly pushing the envelope, constantly seeking new

aspects of middle-class life to be outraged over. It was a wonderful

persona, a great act, but he paid the price — as so many of the greats

do. Feeling so intensely, struggling so hard while pretending he

wasn’t. It was a hard life, one that required extensive chemical

stimulation (he thought) to keep that edge.

He fell off the edge too soon. He died with the Nixon era he

satirized so well, and to me that’s the bigger tragedy, not the how or

the why but the when. Like Moses before the Hebrews got to the Promised

Land, he couldn’t go there with us.

We’ll keep the laugh light out.