Think of this as Volume 11, Number 24 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I’ve written since 1997. Enjoy.

Thanks in part to best-sellers like Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland, and in part to their own self-referential nature, TeeVee blowhards are falling all over one another to compare this year with 1968, the year of the last American crisis.

I started playing around with this two years ago as The 1966 Game, and while it’s fun it’s really very bad historical analysis. It does nothing but look backward. It teaches us nothing about what’s coming.

While it’s true we’re in a crisis period, the nature of today’s crisis is quite different from that of 40 years ago. The 1960s were a social crisis, in which the previous era’s foreign policy assumptions were validated and became the new political divide.

The current crisis is economic. Those old assumptions have fallen apart. They led us into Iraq. We the People no longer believe them. All this constant harping on 1968 does is justify those assumptions anew, trying to make John McCain the New Nixon, Barack Obama the late Bobby Kennedy.

It’s stupid. It’s brain dead.

Every generational crisis in American history has been different. Every emerging Thesis has been different. But there is one such crisis to which valid analogies can be made.

1896.

The 1896 Crisis was the only one in which the majority party going in was the majority party coming out (maybe that will get the bloviators interested). But more important it was about economic organization and America’s place in the world.

The 1890s created America as a single national market, with national brands, an industrial organization, and an imperialistic sense of itself. At the heart of solving the crisis was the Spanish-American War of 1898, which not only gave us Teddy Roosevelt (the crisis’ central figure) but also gave us our first true foreign possessions. We even fought a colonial war, in the Philippines, to keep that empire alive, and created Panama out of Columbia to extend that empire.

The current crisis is in some ways a mirror image of the 1890s. In others it is its polar opposite. The trends, thanks to technology (which also drove the 1890s) are leading us in a new direction:

- The Internet is the new railroad.

- Knowledge is the new resource.

- Sustainability is the new industry.

- Consensus is the new imperative.

Let’s take a look at these trends, one at a time, and see what they portend:

The Internet is the new railroad.

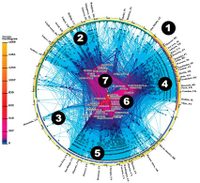

(Diagram of Internet server locations from Discover Magazine.)

The railroads of the 1890s (eventually supplanted by the Interstate Highway System) tied the country together, and made one nation out of many regions. Today’s Internet is the tie that now binds us, but it binds us as one world, not just one nation.

Today’s Internet is about the same age as the national rail network was in 1896. Like the rail network it has been built over roughly a generation. It changes the way we must organize ourselves in a thousand different ways, many of which we’re still blind to.

One change is in the media. The Internet is our new medium of choice. TV was immediacy. The Internet is a firehose of immediacy. TV just had to be turned on. The Internet must be navigated. And unlike all the other media which came before it the Internet can embody every stage of the marketing process — from identifying customers through customer service. It can also embody much of our management and production processes.

The Internet has begun what might be called the de-industrialization era. The Internet enables mass customization, one-to-one connections between consumers and producers, not just for the first time but worldwide.

What does all this imply? That the nation which uses the Internet best, and delivers the Internet best, is in the best position to make economic (as well as social) progress.

Knowledge is the new resource.

Richard Florida (left) in his Creative Class books (the latest, Flight of the Creative Class, is a must-read) was among the first social scientists to grok this simple fact.

Research universities are our new factories. Minds are their raw materials. These minds create the industries of the future, and those industries wind up centered near the universities.

Silicon Valley and Stanford were the model for this. But most growing American cities now have their own equivalent. Rice in Houston, Harvard and MIT in Boston, the Research Triangle in North Carolina, Emory in Atlanta, UT in Austin. Basic research becomes applied research becomes products becomes businesses and industries. America’s dominance in the 1990s (and its potential in the 2010s and beyond) is bound inextricably to these research institutions and the products they dream up.

So why are we subsidizing heavy industry? Why are we obsessing over oil? We should be, we must be, about the business of replacing mass production with customization, and oil with renewable hydrogen. What we need are hundreds of new Stanfords, new Rices, new Emories and new Dukes. We need to extend elite education into the mass market, and in-depth knowledge into as many minds as can take it, using the Internet.

Out with the military industrial complex. In with the research educational complex.

Sustainability is the new industry.

Whether we’re at peak oil or not is irrelevant. Our national independence and economic independence demand we win the War Against Oil, that we replace hydrocarbons with hydrogen.

Many of the raw materials we most need are buried in the new mines of the 21st century. In the 20th we called them landfills. Minerals, metals, plastics, natural gas — it’s all there, ready to be exploited. All it needs is a price which will make exploitation pay. That’s the key benefit of today’s crisis — it is creating those prices.

The great political divide of the coming years will be right here, between those who see sustainability as an economic imperative, a national security imperative, and those who think we can live in the past by exploiting new forms of hydrocarbons — oil sands, coal, etc. etc. When you exploit hydrocarbons you’re part of a dysfunctional worldwide market, one controlled by whoever holds resources. Only when you break from that past do you gain economic independence, and exportable technology.

That’s why need to go green. Not for the Earth. For America. And this motivation guarantees we’ll go there.

Consensus is the new imperative.

Consensus in this case means more than a general national agreement on the direction we need to take. That’s easy to get, but very difficult to sustain for more than a few years.

What we need to reach for is a global consensus. This is what the internationalization of business, and the rise of the NICs (Brazil, India, China, etc.) is really pointing us toward. America can’t force the world’s hand. We can lead, but only in concert with others.

The way to lead in this new era is to find where we agree with other nations and work outward from there. We should concentrate first on drawing lines where national governments cannot and must not be allowed to go — genocide is a good start. Governments which commit genocide against their own people lose their own legitimacy, and the leaders of those governments lose the right to power, even to liberty. Zimbabwe, Darfur and Burma are, in fact, more important to our future than Iraq and Afghanistan, because they offer opportunities to create and (more important) enforce this most basic consensus.

That’s why we need trials against today’s criminals, starting with George W. Bush. They are our ante in the new international game. You can’t condemn Mugabe for murder if you can’t condemn Bush for Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. You can’t try the one if you won’t try the other.

Economic arrangements must be equal and reciprocal. Free trade can only exist on an equal basis between countries with equivalent industrial and political systems. A free trade agreement between a consuming country and a producing country is mere mercantilism. It is national feudalism.

This last section, as you see, is fairly aspirational, general, almost unformed. That’s deliberate. Because that’s the future. That’s where we need to be going.

Concluding Thoughts

Electing a leader with a Clue, like Barack Obama, does not solve the present crisis. It only begins the search for solutions.

Until we get to Obama, however, we can’t begin to address questions like those I have posed. We can barely ask them. The key to our children’s survival in the 21st century lies in finding answers to them.

That is the task we leave them. My generation has made a hash of this world, and the start of healing must be an acknowledgment of that fact, a willingness to accept that fact as part of the new consensus. Along with a willingness to follow.

This is Robin (right) and John’s world now. The Crisis of 2008 says, more than any single event, that the era of the Baby Boom is over. Just as the Civil War era ended in the crisis of the 1890s, in the rise of Industrial America, a single national market, a global power, so this crisis is ending the Baby Boom era, the era of the second Civil War.

A new day is dawning. I wonder how much of it I’ll see? I don’t know. I’m just looking forward to the sunrise. As you should be.

http://www.ourfuture.org/blog-entry/1968

http://www.ourfuture.org/blog-entry/1968