How does a $700 billion injection of your money act as a laxative on the Big Shitpile, and why is this a good deal for you?

If done right, you the taxpayer make a killing. Everyone is selling. You are buying. Remember "It’s a Wonderful Life," the bank run scene (above)? The famous line from Jimmy Stewart’s George Bailey. "Potter isn’t selling. Potter’s buying. He’s picking up some bargains."

Well in this version you’re Potter.

You walk into the market and offer to buy these CDOs, now priced at zero, at some price set by an auction.

Then you take those securities apart. You can do this. You’re the government. Bankers can’t do this. Only you can do this.

You crack open these little piggy banks and look at what’s inside. The reason these securities are worth nothing is no one knows what is inside. Some of these are loans that have foreclosed already. You set those aside. Most are mortgages which are still current.

Now you take a bunch of the best loans, some fixed-rate mortgages, all current, with an average interest rate of, say, 6%. You put them into a new security and you sell them. These are good loans, paying 6%. They’re worth a lot of money.

Then you look at the rest. Maybe you’ve got some adjustable rate mortgages where the holder is unsure if they can make the payments. You go to those holders and offer them a new deal, a new fixed rate mortgage through the government, at a rate somewhere between the souped-up rate they are currently having trouble with and that good 6% rate you just sold. Package these together, figure there might be some defaults, but because of the higher interest rate you can still get a good price for them.

Then you have the crap. As many as one in ten of these loans may have to be foreclosed on — I’m actually being pessimistic here. OK, you foreclose. And you sell that real estate to bankers.

Now you’ve raised a bunch of cash from selling these good notes, so you go back into the market and buy more bad notes. Private bankers see what you’re doing and they enter the market as well. Gradually the backlog of mortgage-backed securities clears.

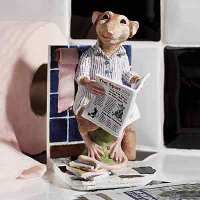

(This is the last unboxed King Rat in stock, just 15 pounds. Hurry before it’s gone!)

There’s a bigger, deeper problem. There are derivatives created out

of the old paper. You want to buy some of this paper to create a market

for it, to help set a price. Maybe you overpay on some of it. But the

paper begins to move. Gradually you get a better idea of what these

notes are worth, based on your work pulling apart the underlying

mortgage securities, and you’re able to pay a more accurate price. The

private market sees your work and they start buying.

This is how laxatives work. They go after the obstruction from the

outside-in, gradually liquefying it so it clears. You spend a lot of

time on the bathroom throne, but when you come out you feel better. (Do what King Rat has done — bring a newspaper.)

But we can’t start this process until we get a big enough pot of patient money together to buy up a bunch of mortgage-backed securities and take

them apart in this way, leaving us with a new collection of assets to

sell. The capital necessary for this operation is too much for any bank

or brokerage to handle. Only you, the taxpayer, have it, because you

can print it, in the form of 3 month treasury bills which are now

paying less than 1%, because they’re safe, government-backed

investments.

I can’t tell you exactly what the bottom line is here. We don’t know

exactly how bad the obstruction is. We don’t know how much we have to

put in to get the obstruction to clear through the market. It’s true

that the Treasury Department basically pulled that $700 billion figure

out of its ass.

But when you’re dealing with constipation, that’s what you do.