Think of this as Volume 11, Number 47 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I’ve written since 1997. Enjoy.

In looking at health care reform I am reminded of an old New Yorker cartoon by Stanley Harris (right).

A scientist stands before a blackboard filled with equations, but with a giant gap in the middle. "Then," he has written, "a miracle occurs."

We’re very much in that position regarding health care reform. Advocates across the political spectrum insist that by automating the industry we can save tens of billions of dollars. Both John McCain and Barack Obama had this in their platforms.

Yet no one in the industry believes it possible.

Over the last 13 years many, many industries have succumbed under the World Wide Web. Where we once went to travel agents we now go to airlines’ Web sites, or (for complex trips) a site like Expedia.com. Where we once went to book stores and record stores we routinely go to Amazon and similar sites. Instead of the library we ask The Google.

Almost as soon as the Web was spun, the rush was on to create special tags to deal with the problems of vertical industries. That’s what XML is. It’s an agreement between market participants as to what customized HTML-like tags will mean, in the context of their business. So we have special XML subsets for the advertising industry and for many others.

But not for medicine.

When I went to the annual HIMSS show in Orlando last spring I felt transported back in time. It looked like a 20-year old Comdex. Each major vendor – Cerner, McKesson, Microsoft — had the equivalent of their own operating system. Each product vendor — and an MRI machine in this case is just a fancy printer — required multiple sets of drivers to move files into any one of these systems. And since you could not be certain that the equipment you bought would include drivers for the computer system you might want to buy, doctors and hospitals remained in statis. Because paper worked.

To break this bottleneck requires a set of standards as universal as paper, defining all sorts of medical conditions and procedures, across all vendor systems and equipment types, so that the whole can interoperate.

Easy to say. Very, very tough to do.

There are groups that are trying to create such standards. Health Level 7 is the most prominent. They require agreement on what to call procedures, on how to define medical processes, an enormous, ever-changing schema that is flexible enough to accommodate the change we know is coming to medicine as our knowledge advances.

It is an enormous undertaking.

Acceptance of this grand scheme is at the heart of Electronic Medical Record (EMR) systems (there are over 200 of them) sold to professionals and Personal Health Record (PHR) systems like Google Health and Microsoft Healthvault, which patients will control.

On top of the former are layered a host of regulations like the HIPAA law, which aims mainly to protect us from abuse by our "health vendors," and it’s partly in implementing laws like this that EMR vendors have created the proprietary tweaks that make it so hard to create PHRs under patient control.

Note here that HIPAA does not really provide security, just bureaucratic control. And security, or the lack of it, is both the biggest fear and the biggest impediment to computerizing. The fear is real.

Now, having described the intractability of this problem, let me offer your Clue.

The problem can be solved.

The answer lies in the technologies I have been covering most of my adult life — the Internet and open source.

The latter springs from the former. The Internet is, at its heart, a set of universal technical agreements that allows data to flow without money or cost being a consideration, and to be translated for use by open, universal, royalty-free standards. Open source uses this medium to eliminate distribution costs, cut marketing to the bone, and create new solutions that can be used and extended by anyone.

Many people at my current shop like to argue about the nature of open source. Is it a business model? A development model? A breath mint? How do you get money out of it? And if you can’t get money out of it, what is its real value?

At its heart open source is merely a set of contracts operating under the premises of the Internet. Open, standard, transparent, fair. Equal rights and equal responsibilities. You can define this premise in different ways, and so we have a variety of open source contracts — BSD, GPL, and all their variants. But at the heart of each is this simple set of concepts. Technology should be freely available. Anyone should be able to examine it, and extend it.

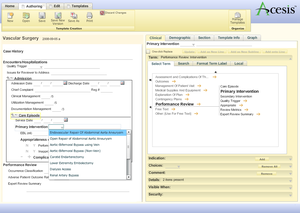

Today I spoke with a man named Kevin Chesney. His company, Acesis, is trying to automate something that has not yet been automated — the peer review of hospital cases.

In order to do this Chesney and his team solved the problem. They employed open source technologies — Adobe Flex for presentations, Java Spring for middleware, SQL databases at the bottom of the stack, and XML to connect it all.

This, along with HL7, can be become the heart of what I call the Health Internet.

The Health Internet will be a royalty-free way of transferring even the most complex medical data among all stakeholders in the medical process — government, insurers, banks, hospitals, doctors, patients. Vendors will translate their present systems to these standards, and their competition will in part be based on how well they meet them, how complex the resulting files might be, how complete.

The Health Internet, through open and royalty-free standards like Java and XML, will expand in reach and sophistication as vendors adapt their current offerings to it, just as the Internet, HTML, and open source have expanded as their standards have become the basis of competition in other markets.

To make this happen policy makers have to put down a marker. They have to demand that vendors act in concert, and that the Health Internet come into being. They can do this just as they acted to create the current Internet, funding the necessary links and supporting the standards bodies defining it.

This is not an easy hack. Medical computing is highly complex, far more complex than any single vendor can conceive of.

But the force of consensus can bring it together, if we’re committed to it. Think of it as the Internet Thesis of Consensus in action.

Call me crazy – stupid, naive, whatever – but it seems to me that medical records, like any others, hold essentially the three kinds of data that every other database record on the planet also holds:

words, numbers and pictures.

Or, if you want to split hairs, generalize pictures to the broader term ‘media.’ That way the pictures can move and even sing the national anthem if you want (Okay. I’m being irreverent. They can record a heart murmur.)

Seems to me the file formats to handle these data types have been around since the Lewinsky administration: .doc, .xls, .jpg, .mov, .pdf. If it weren’t so late in the day I’d even spot you an .aiff, a .gif and a .swf.

When a technician (or a doctor) digitizes a film of your foot, why must the resulting image file have some sort of proprietary format – aside from the fact that no single entity gets to develop a proprietary format and earn royalties on its use?

Then, why do we (the collective we; I’m an ad broad) have to assemble the data fields into a proprietary record format? Filemaker and Access make pretty good databases, too, I’m told.

And don’t say HIPAA unless your doc’s office staff is – for that reason – transcribing hard-copy patient charts into Swahili before they go into those massive vertical floor-to-ceiling cabinets that hold all the patient records. (And, when I think of all the duplicate intake forms, filled out in longhand, plus the wasted keystrokes those file cabinets are holding, it practically makes me want to weep in frustration to see the person-hours it would take to build a patient-records base that enormous. (And that nobody can find anything in!)

If it were me, I’m not sure I grok our fascination with open-source. Seems to that in this economy, off-the shelf would be a better way to go.

Call me crazy – stupid, naive, whatever – but it seems to me that medical records, like any others, hold essentially the three kinds of data that every other database record on the planet also holds:

words, numbers and pictures.

Or, if you want to split hairs, generalize pictures to the broader term ‘media.’ That way the pictures can move and even sing the national anthem if you want (Okay. I’m being irreverent. They can record a heart murmur.)

Seems to me the file formats to handle these data types have been around since the Lewinsky administration: .doc, .xls, .jpg, .mov, .pdf. If it weren’t so late in the day I’d even spot you an .aiff, a .gif and a .swf.

When a technician (or a doctor) digitizes a film of your foot, why must the resulting image file have some sort of proprietary format – aside from the fact that no single entity gets to develop a proprietary format and earn royalties on its use?

Then, why do we (the collective we; I’m an ad broad) have to assemble the data fields into a proprietary record format? Filemaker and Access make pretty good databases, too, I’m told.

And don’t say HIPAA unless your doc’s office staff is – for that reason – transcribing hard-copy patient charts into Swahili before they go into those massive vertical floor-to-ceiling cabinets that hold all the patient records. (And, when I think of all the duplicate intake forms, filled out in longhand, plus the wasted keystrokes those file cabinets are holding, it practically makes me want to weep in frustration to see the person-hours it would take to build a patient-records base that enormous. (And that nobody can find anything in!)

If it were me, I’m not sure I grok our fascination with open-source. Seems to that in this economy, off-the shelf would be a better way to go.

I find it interesting that Mary Baum derides both the proprietary and open source in the same comment.

Open source and non-proprietary standards go hand-in-hand and promote adoption and consensus, while proprietery formats and closed source limit adoptibility and hide things from the user and those who might want to interact with your software.

HL2, X12, and EDIFACT are existing standard data formats that have been around for a while, and exchange of these is regularly electronic at some level. Even when paper forms are used, these are usually scanned via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) into a computer.

But those are mainly used for interaction between parties, not storage and processes within the provider and payer. We need standard formats and processes inside the health enterprise, not just between them, for totally-electronic health care “paperwork” to be a reality.

Proprietary, closed source methods have been the status quo there for a couple decades, and witness how well that’s served us. We need change, in the form of open source, standards, and consensus.

I find it interesting that Mary Baum derides both the proprietary and open source in the same comment.

Open source and non-proprietary standards go hand-in-hand and promote adoption and consensus, while proprietery formats and closed source limit adoptibility and hide things from the user and those who might want to interact with your software.

HL2, X12, and EDIFACT are existing standard data formats that have been around for a while, and exchange of these is regularly electronic at some level. Even when paper forms are used, these are usually scanned via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) into a computer.

But those are mainly used for interaction between parties, not storage and processes within the provider and payer. We need standard formats and processes inside the health enterprise, not just between them, for totally-electronic health care “paperwork” to be a reality.

Proprietary, closed source methods have been the status quo there for a couple decades, and witness how well that’s served us. We need change, in the form of open source, standards, and consensus.

Thanks for sharing the health on internet. Which makes tips to get information on health care system.

Thanks for sharing the health on internet. Which makes tips to get information on health care system.

Thanks for sharing the information. Very good information. really helpful for our life.

Thanks for sharing the information. Very good information. really helpful for our life.