Think of this as Volume 12, Number 3 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I've written since 1997. Enjoy.

Hard as it is for you to believe moments like this, when times are darkest, are those offering the greatest opportunity.

- Everything we value in California grew up during the Great Depression — its farm belt, its media, avionics and technology all date from the 1930s. Even Las Vegas.

- Apple and Microsoft grew up alongside the recession of the early 1980s.

- Google emerged from the dot-bomb at the start of this decade.

What can we learn from successes like these? The people behind them were passionate first about the product, then about the customer experience, and only later about the money. None of their creators listened to the pundits of their time. They focused on doing something they felt needed doing for its own sake.

We know what our country needs. What's lacking is the imagination and drive to make it happen. Or what seems to be lacking — I have no doubt that there are people, right now, out of sight of both this blog and the TV cameras — working on solutions.

You should be one of them.

So let's look at some of our most intractable problems, and then you look for ways to solve them:

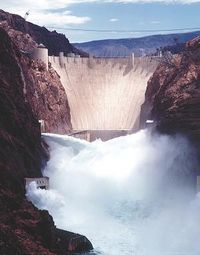

The low-hanging fruit here lies in saving energy, not creating it. But the big opportunities lie in creating it, delivering it, and storing it.

Solar power, wind power, and geothermal power have this problem in common. On a nice, sunny day you may make more than you can use. What do you do with it? Already we're seeing some wind projects fail because their capacity is considered excess to requirements at certain times.

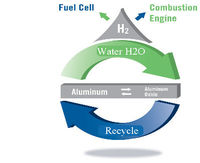

The obvious answer to this lies in the hydrogen cycle. Create hydrogen from water in order to store energy for later use by fuel cells. Should this be done in the form of H2 gas or NiH3 ammonia? Perhaps neither. What we really need is a stable structure for holding indefinitely and releasing at a variable rate hydrogen molecules.

We need new business models that will make the creation of solar and wind energy as profitable for consumers as they now find insulation and low flow toilets. Should this be done on an individual level, a neighborhood level, or a city level? You can answer that problem at a profit.

We need standards for the exchange of hydrogen and power. We require the infrastructure to make this happen, transparently. Some of these standards could emerge through the Internet, others through new types of chips and sensors. Work on all these things should begin now.

One more important point. When we make the movement and storage of hydrogen possible, we also make it possible to create water at the point where it is needed, rather than relying upon the caprices of nature. But systems for saving the "pollution" of fuel cells, for storing it and recycling it, and business models for making all that work also have to be created.

Our parents' aging model, which involved strict segregation, gated communities, and retirement centers far from our urban core, is dieing. We need a new one. (From the 2004 movie The Notebook.)

The most important task before us will be replacing people with computer systems. What I have called Always-On, chips and sensors and applications which live in the air, need to become a way of life.

Aging in place is a complex process. What works for people in their 50s may not work in their 60s, or 70s, or 80s. And a lot more of us than you think are going to make it into our 90s. We need to do this where my friend Edna House, now 95, is doing it. At home. This will require an immense expenditure on assistive technology, an unimaginable number of new inventions, and opportunities to make a whole lot of money.

Again the low-hanging fruit here lies in saving labor, in replacing doctor visits with data exams, and nursing visits with automated technologies.

In the last century mankind has destroyed the natural order and thrown evolution into reverse, everywhere. (That's a liger cub. Cute, but he should not be.)

I'm talking about more than global warming here. I'm talking about replacing the old balance of predation-and-prey with a new artificial order created and maintained by hunters. I'm talking about replacing animal populations that once lived in balance with invasive plants and animals that decimate whole ecologies.

This must change. Natural predation must return. But how do we do that in a world where man's presence is ubiquitous, and the comfort of any single human is considered sacred when compared with that of any animal, or any population of animals?

Answers to these questions have yet to be researched, let alone implemented. This is an enormous growth market.

We have ignored the vastness above our own atmosphere for nearly a half-century, ever since its value as a military marker dwindled to zero.

Getting back will require dramatically reducing the cost of transferring material out of the gravity well. It will also require cleaning up the mess we've already left.

There are answers, in space, to manufacturing and energy problems that seem intractable today, but we must get there in order to seek those answers. Today's rockets won't get the job done. We need something else. Whether it's a space elevator (shown) or some other mechanism, the need is obvious and the opportunity equally obvious.

These are just a few small examples of the great tasks which lie before us, and before our children. The time to begin the work is now, while the wreckage of the old order lies all around us.

My best advice is not specific here, but very general. Consider the swamp, not the alligators. Dream big, then dream bigger. Be brave. That's what the best of us, and our forefathers, did.

Your turn now.