Think of this as Volume 12, Number 12 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I've written since 1997. Enjoy.

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | M – Th 11p / 10c | |||

| Jim Cramer Unedited Interview Pt. 1 | ||||

|

||||

Who does a journalist serve?

Readers.

The question gains greater urgency in the wake of Jon Stewart's take-down of CNBC because he was asking the right question.

When I write here I serve myself. I may make a pretense out of serving a reader, but I have learned in the last years that, for me, writing about the world is a compulsion. I have done it for nearly 50 years, and given that I'm 54 you get the idea.

Writing is how I make order of the world, and when I'm writing I'm my own reader. I do try to read all these posts out loud before hitting publish. I do it for tone, to catch mistakes, and because (frankly) I'm a fan of my own stuff. I'm glad you are, too, but I wonder if I'd stop if no one read me here. Doubtful.

In writing for money – and I've been doing that for over 35 years now – the rules are different. There I serve the reader.

The difference between journalism and regular writing is that a journalist defines their audience. As I have written many times, especially recently, "journalism is organizing and advocating a place, an industry or lifestyle." It helps to be part of what you're writing about but it's not a necessity. Instead just try to walk a while in the readers' shoes. Ask yourself, what do they think? How do they see the world? What do they want to know? And go from there.

In defining all this a publisher and editor are vital intermediaries. The editor defines the reader for you. The publisher defines the market, which is more important. The market consists of the readers, and all those who wish to get the reader's attention. Not just advertisers, either, but sources, players, whoever makes the community you serve tick.

If you serve a city, for instance, the mayor is important to the publisher. They are of interest to the editor and they are the subject of the journalist. They may be a source, but they may also be a story subject, the target, or just an interest to consider. The editor considers the mayor's interest in the context of the readers' viewpoint, while the publisher takes the wider view — what can the mayor do for us, or to us — is it in our long-term business interest to be with him or her or against?

It's here we get to the nub of the matter. A publisher may decide to serve the mayor, as being in the publication's business interest. The editor must treat with the mayor, as an important person in the community. The journalist must take a step back from the mayor and try to see him (or her) only from the reader's point of view, because in journalism that is who the journalist serves.

Let's take this back to the business beat, which is where I've done most of my work.

The industry or business community you cover is both the source of your stories, your advertiser, and your reader. The journalist must seek to uncover only the reader's interest, and view businesspeople as sources or targets of the work. Nothing more.

That's what CNBC forgot, what the business press as a whole willfully ignores, and has ignored ever since I started in the business. Instead, too many of us identify with our sources, and take narrow advertising interests to be those of the reader. They are, often. But not always.

Maybe it's easier to visualize if we look at sports.

In covering sports, you're mainly covering a lifestyle. The reader is easy to see, the "fan." All sportswriters are fans of the athletes and sports they write about. We're kids in a candy store. But we know, even while we're using our heroes for sources, that there must be a distance. They're not the reader. The fan is. When the athlete screws up, either on the field or off, we have an obligation to readers not to cover it up, but to go after our heroes. Most do.

Sports stands in a curious relationship to the whole world of journalism. All sports are a business, a highly-proprietary business which feels it has the right to give, or deny, all outlets the right to cover what they do. They often restrict even the scores of games, seeing it as an asset to be licensed. "Any pictures, descriptions or accounts of this game, without the express permission of Major League Baseball, are strictly prohibited." They take that seriously.

Against that must be balanced the fact that, without coverage, sports don't exist. If a game occurs and no one sees it, or cares about it, it was just a game. A "sporting event," on the other hand, requires paying customers and ample press coverage — before, during and after. As daily newspapers die off, many sports franchises feel a sense of crisis, because without general coverage their audience is limited to those who self-identify with the team. The casual fan, the non-fan, has no connection without general interest "news" about the team reaching every segment of the community.

Thus there is balance. Journalists must be allowed to represent readers, because without readers there are no fans. And no business. No sport.

Now let's go back to business news.

Most business "news" occurs with or without news coverage. Business is the source of funds for journalism, for sports, for everything. Without the money there is nothing else.

Thus business always has more power over journalists, editors and publishers than anything else we write about.

Still, there is a "reader" interest that is distinguished from that of the businesses we cover and advertise, and most journalists understand it. Within an industry the reader wants fair dealing. Within a community they want growth and a level playing field. Even within finance, there's a reader interest. Investors want to know the game is not rigged against them.

It is this interest business journalism has generally failed to serve. Instead, enamored of business as a source of advertising, or a source of "celebrity" type copy, we've served the sources and advertisers, not the readers.

The vast majority of business publishing is 100% dependent on the businesses it covers advertising with us, and usually that makes us dependent on a relative handful of businesses — the largest, the most dominant, those most likely to screw the readers.

In the computer press, we're talking about Microsoft in the U.S., although in Japan other companies play the same role. Microsoft essentially created the computer press, and when it lost interest in advertising there it killed the computer press.

That's a simple business transaction, easy to understand. But over the last few decades, with the rise of cable television, this changed in the world of finance.

Simply put traders became worth their weight in gold as celebrities. Not as advertisers, but as "players," in the same way athletes are valued as players. And financial journalists, to their shame, forgot that the players are not the game. Instead of considering the best interest of the sport, as sportswriters do routinely, they considered the interests of the celebrities they were interviewing to be the same as the system they were covering.

To be fair, government did too. Starting during the Clinton years, but especially during the Bush years, the business of business ran without a "commissioner," someone aware of a higher interest, someone who could put the hammer down, through an expedient as simple as calling in a reporter to give them a story off the record. Bud Selig was the George Bush of baseball. He claimed to support the interests of the game, but it was only his own interest he cared about.

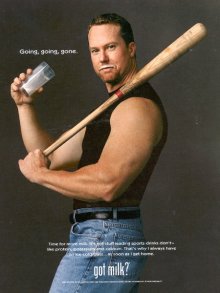

Now compare the behavior of sports journalists over the last decade to those of business journalists. Sports Illustrated and ESPN covered the steroids scandals, and suspicions of those scandals, from the very beginning. They pushed constantly for reform, warned constantly of the consequences. Fans knew. We knew. Heads don't grow that big by themselves. Athletes don't look like that in their 40s.

But business journalists? Not a word. Nary a peep. A few reporters did look into aspects of the "big shitpile" story, but very few, and editors did not push their stories, nor did publishers advertise them. Instead they were obsessed with the celebrity of the players. Money became a spectator sport.

That's what Jon Stewart was complaining about and he was right to do so. As it was in the time of the medieval kings, only the court jester could speak the truth.

The great shame is that the journalists could still think of themselves as kings. Which too many do.

The answer to these scandals in business reporting is, as Stewart suggested, to return to the readers' interest. The readers are not the Wall Street sharpies. It's the small investors on Main Street, the grandmothers we preached "long term investing" to, who are now out half their assets (or more), while these ass-clowns continue defying the public weal.

At least baseball finally got rid of Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds. We in the business press need to undertake the same campaign against our equivalents. Because the journalist's responsibility is not to the advertiser, or the source.

It's the reader you work for. And if you forget that you don't deserve readers. Or viewers.