Think of this as Volume 14, Number 26 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I've written since 1997. Enjoy.

Elections, by themselves, don't solve crises. They begin them. They set a political force against serious momentum, bent on transforming the country by tearing at its foundation. The success of the new movement is never guaranteed.

The problems of the time appear intractable. The uphill fight seems endless. Then, just when it's needed, an event occurs that allows the thesis to move forward, that shifts momentum just enough so that the thesis leader gains confidence and moves as he knows he must.

- During the Civil War, this was the Battle of Antietam. (Above, from Matthew Brady.) It was a bloody, narrow victory, which mostly turned on luck, when Confederate orders were captured. But it was enough to move Lincoln toward proclaiming the Emancipation Proclamation, which while it nominally freed slaves only in areas in rebellion, transformed the war from a struggle over commerce to one over human liberty.

- For the progressive era it was the Spanish-American War. It boosted nationalism, made Theodore Roosevelt a hero, and made America a world power, so he could stamp the age with a progressive thesis of slow, steady reform meant to maintain social peace and order.

- For FDR the crisis really came in 1935, when the National Recovery Act was declared unconstitutional. Much of its work had already been done, but the rejection gave Roosevelt an enemy he could focus on, rally people against, so the alphabet soup he created against the Depression might have a chance to change public attitudes.

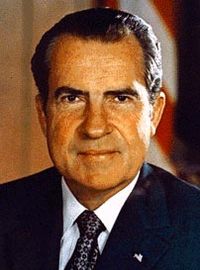

- For Nixon the crisis was Cambodia. He sacrificed an entire people for domestic political advantage and it worked. The war, and the war against the war, united conservatives and also gave Nixon the image he needed to open China, which in the end may have been his most important legacy.

In all these cases there was one crisis, and one event, threatening the national future. There was one action that served to give the new thesis momentum.

This crisis is not like that. The Bush era didn't leave us with just one legacy, but a host of crises just waiting to explode. The financial crisis. Two wars. Deregulation, and a feeling among businesses they could act with impunity, that the cops would never come.

But at the heart of all is a more existential question, the immediate past demanding to rule the unknowable future.

Just as the assumptions of the Civil War period set the stage for the 1896 crisis, and the slow pace of progressive change made Roosevelt necessary, and the hubris of America's governing power made Nixon necessary, so Nixon-ism holds the seeds of our present difficulties.

It's not what we think that divides us, in other words. It's how we think. Read the comments here if you don't believe me, on items like In Extremism No Liberty or Kill the Liberals. Notice the projection, the assumption of ill will, among the conservative commentators. And notice how, when called on it, they call me names (and how, sometimes, I forget myself and respond in kind). It's not an argument, it's The Argument Clinic.

You can't have a discussion about anything without ground rules, without an assumption of goodwill. You can't have a real democracy if both sides can't live in the same moral universe, if one side insists on its own facts, if every proposal draws contradiction because of where it comes from.

Of course that's not how it's covered, because journalism always internalizes the previous thesis, and doesn't admit the new one until after the crisis has passed. So everything is covered as "he said" and "she said," as though there was real debate over the facts of evolution, or climate change, simply because two sides are screaming at one another.

What can be the Battle of Antietam in this case?

Today's alliance is as uneasy as that one was. The truth today is as it was then — rich man's war, poor man's fight.

Either a portion of the elite must be persuaded by events they can do business with Democrats, and that they can't with the Tea Party, or elements of the Tea Party must become discouraged by events into understanding where their economic interests actually lie.

While Lincoln was usually losing his battles in 1862 even while winning the war, President Obama seems to be winning his battles while losing it. Global policymakers are marching away from Keynes and toward Hoover, the foreign war that might have galvanized patriotism is going badly, and the continuing BP spill leaves everyone with a feeling of hopelessness, of "no we can't" rather than "yes we can."

Despair is the real enemy. In an existential conflict it's not about victories or defeat, but our attitudes toward them, that count. Antietam merely beat back a foreign invasion. The Spanish-American War was a potemkin conflict, its claim of liberty masking he real cause of empire. The economy remained depressed throughout the 1930s, and the Vietnam War eventually was lost.

Yet these events set theses in motion that lasted a generation because they changed attitudes permanently. Antietam unified the North, the Spanish-American War made Americans feel important, the New Deal gave people a sense of shared effort and shared sacrifice, while Vietnam unified Republicans.

What happens is less important than how we're made to feel about it. The cause, the call, the ideals, must be clear. And any event that creates hope must be seized upon.