In terms of this technology transformation, we're about where PCs and the Internet were at time time in 1970. Back then, you'll remember, Intel was just starting work on what would become the 4004 chip and a researcher had just sent-and-received the first online message.

Skepticism abounded. Computers were seen as giant machines useful only in accounting and scientific applications. New "minicomputers" from companies like Digital Equipment Corp. were starting to drive prices down. But the main interfaces remained the punch card and the print out.

We're at the same stage today with energy technology. Skeptics abound. Working, cost-effective systems seem thin on the ground.

Windmills work, the technology is stable, but they cost big money to erect, they do require maintenance, and each new windmill increases our supply of wind energy by one unit. Geothermal units work best where a source of Earth heat is relatively too close to the surface (to minimize drilling and energy loss from lifting the hot water) but the underlying rock structure is stable. We have not yet learned how to tap volcanoes.

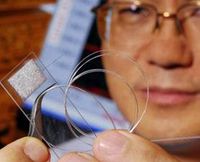

There are three dimensions toward improving solar — cost, efficiency, reliability. Some interesting work is going on with organic compounds, but there's a reliability problem there. More interesting work is going on using carbon nanotubes to increase efficiency, the problem there being scaling manufacturing. A third avenue of research involves using very short optical cables, coated with zinc oxide, which can produce energy with a very small footprint. The problem here is efficiency — right now a bundle of fibers the size of a ponytail will power a light bulb.

Now, here's why the skeptics are wrong. All the stories and links I delivered in the previous paragraph cover work being done within 10 miles of my Atlanta home. Atlanta is just one city. We're talking here mainly of one university, Georgia Tech, and its spin-offs. Atlanta is not the center of solar research — there are literally dozens of such centers around the country, and more elsewhere in the world.

All these researchers communicate with colleagues. All of them have access to enormous processing power on their desks. All of them can take complex calculations to the cloud. All of them have labs filled with eager, young graduate students. We're building the future on the backs of the immediate past, on top of microprocessors and networks that were just a gleam in the eye of cutting-edge researchers and virtual start-up companies just 40 years ago.

And then it accelerated. And accelerated again, and again, and again. Money began pouring into the space as it proved profitable, and the world was gradually transformed. Accounting that once required armies of drones can now be done on a desktop. Coordination that once required dozens of plane rides and conferences can now be done instantly, from researchers' desks.

The same thing is going to start happening with regards to device energy. There have been wrong turns and there will be more. A lot more basic research remains to be done than was required in 1970 to create today's Internet. But the Internet lets us do that research, and share those results among experts or the world with the speed of light.

Within the liftime of my children today's energy shortage will become a super-abundance of energy. If you don't believe me, fine. I know this is the future because I've seen it, again and again, in the past.

It's the best story of our time and I'm proud to be on the ground floor.