Think of this as Volume 14, Number 47 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I've written since 1997. Enjoy.

When I first started studying our political history here and looked for patterns, almost five years ago now, it was with the assumption that political change leads society's changes.

When I first started studying our political history here and looked for patterns, almost five years ago now, it was with the assumption that political change leads society's changes.

What I have found is just the opposite. Politics lags, badly. It always lags.

The political subtext of the TV show "Mad Men" involves politics. The agency is contacted by the 1960 Nixon campaign, but the campaign eventually backs away. As time goes by the protagonist, Don Draper, increasingly identifies himself with the Nixon story of the "self made man." In next year's final season, my guess is he'll be falling and flailing, but the political habits of his future life will be set in stone. And the Nixon order will finally come in.

The Nixon Thesis, in other words, wasn't created by his 1968 victory, nor by Spiro Agnew's 1969 speeches. It was set in motion by previous events. Society leads politics.

But which society changes are we talking about? Not the kind you think.

Political changes are driven by economic change, not social change. A new political thesis (and the people around me are heartily sick of that term) actually results from economic changes.

-

In the 1960s, the rise of the transistor and the profitability of content industries.

In the 1960s, the rise of the transistor and the profitability of content industries. - In the 1920s, the rise of a consumer culture and a middle class.

- In the 1890s, the need by farmers and manufacturers for steady prices on new infrastructure like railroads and electricity.

- In the 1850s, the rise of manufacturing, machines doing work formerly done by people.

Notice that all these industrial changes predated a political crisis. They also were not what politicians or the media were commenting on. Each crisis was also launched by old industries capturing the political system — slaveholders, railroads, financiers, manufacturers.

In our time, oilmen.

The real leading indicator is not public opinion, and not the changing media mix. It is, in fact, the economy, stupid.

What has happened in the last decade is just as profound a change as what Gordon Moore foresaw in 1964. And equally obvious.

This has created an economics of scarcity. Each time the economy seems on the verge of growing, the price of resources in the marketplace rises. It's a monopsony — the market has created a single point of sale, the spot price of oil, which rises at the first sign of increased demand, soaking up society's profits.

In any era of scarcity conservative forces hold a political advantage. People see change as bad, they hold on to what they know and have. Wealth flows upward, because it's increasingly rare, and fear rules the day.

Scarcity is what triggers political change. Americans resist scarcity and limits instinctively. The very idea of America stands against it. If there is any political genius to the American mind, it is this demand for abundance.

We have also seen, in the last decade, a slow rise in technologies aimed at harvesting energy and returning us to an economics of abundance.

-

Some, like geothermal, come out of the old oil business. You dig a well, you pump water into it, and as hot water is forced upward you extract its heat to make electricity.

- Some, like wind energy, come out of the manufacturing business. A modern windmill is an industrial good with a predictable cost and predictable payback. The capacity of a wind farm grows arithmetically.

- Others, like solar energy, come out of the technology business. The solar cells of 2008 were far more productive than those of 2006, and those being produced today are more efficient still. These improvements go across a number of dimensions — life span, cost, effectiveness.

The great economic promise of our time lies in harvesting the energy all around us with devices, especially devices whose economics (like those of solar cells) can obey Moore's Law.

But here's the real hope. Moore's Law, and its promise, can be found in more than the ever-increasing cost effectiveness of solar cells. They also emerge from technology itself.

Consider.

The real canary in the coal mine for our economy is the price of Intel stock. After increasing 10-fold during the Internet boom, it remains mired near its post-bust levels, about $20 per share. Demand has not kept pace with chip supply. Our imaginations — what can we do with more storage, more processing, more network capacity — have not kept pace with what the industry can provide us.

We have been failing the test of abundance.

The economic challenges of our time can overcome this. We have the computing power to design products at the atomic level, and in energy harvesting we have a challenge big enough to soak up that power. Distributed computing through the Internet can now handle an enormous number-crunching job with ease. The limit is our imagination.

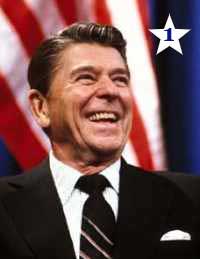

It's in calling on our people to use their imaginations and the abundance we have to create more abundance that politicians can be useful. Every new political thesis has optimism at its core, a belief that the future can be better. Even the Nixon Thesis, as anyone who saw its validation in Ronald Reagan will attest.

But neo-Reaganism, unlike Reaganism itself, is not optimistic. It is too wedded to the idea of finding and crushing enemies to be that. We have gone the Bush Road too long for it ever to regain its luster. The ambulance crashed, and setting it on the same path won't stop it from hitting the wall of rising resource prices.

We need something new, from ourselves, from our economy, and from our politics. We need an agenda, an economics, and a politics based on abundance, on the promise of the positive change I can see all around us.

Whoever delivers that wins the future. Because that's what our economy is going to give us.