NOTE: The following bit of fiction was written under a challenge from my friend Martin Bayne, whom I have watched over the last decade turn into a real good short story writer.

Martin's work combines the best of O.Henry and Rod Serling. His pieces are short, spare and usually have a surprise kick at the end. He has been in long term care for most of the last decade, and presently resides in an assisted living facility in Pennsylvania. But he's a grand gentleman.

Enjoy.

Youth is the gift everyone squanders. Repent that at leisure, when you fight every day for one clear moment. When it's on you, you don't notice it. You mainly see what you don't have.

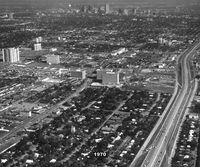

I didn't have money, nor fame, nor was I handsome. I drove a 1964 Chevy, the gift of a dead man through my wife's family. I drove it in Houston, which in 1979 was bathed in the glow of oil fires to the east and a real estate boom to the west. At the center of town some bank was building a 50-story building shaped like a dollar sign, clad in green glass. My old editor was working on the bank's annual report, but I was on my first job, as a new reporter for a weekly business paper.

Good times were rolling but not for me.

The invite lay snug in my suit jacket as I drove down the West Loop, pulled off onto the access road, and found my way into a new office-hotel complex overlooking “the river,” actually a creek bottom called a bayou. Trees shaded it from the street. Let other buildings show off by rising to the skies. This one did the same thing by hunkering down.

The parking lot smelled of new cement, but the spaces were narrow. I felt my way through, somehow avoiding the pillars, and thought what a good boy I am.

The suit fit badly on my pencil-thin frame. My beard looked scraggly, and it was obvious to everyone when I walked into the ballroom that I didn't fit in. But my credentials were in order, I had my business cards, they knew what I was about.

I scanned the room. There was a buffet table at its center, piled high with giant shrimp and cocktail sauce, along with a giant ice sculpture made of the company's initials. Most of those in the room wore fine clothes but looked anxious. They were as old as I am now or older. They drank in small, anxious clusters, looking around for the other money, avoiding my glance, doing a dance with their eyes to which I was not invited.

Which was fine by me.

I went to a second bar and took a second drink. A gin-and-tonic, I remember. Something sharp, with ice, highly alcoholic, with a lime wedge. It would do what I needed to have done.

Scanning the room again, feeling lonely and out of sorts, I saw a couple I recognized. He taught at my former college. He had once been powerful, I knew, but now he was semi-retired, or so I thought. Word was he was running for office, but the money wouldn't touch him here. It was another man's crowd.

So feeling sorry over the couple's isolation I sidled up to them. I introduced myself. They shook my hand. We drank. I moved away. They were still being avoided so I came back. They actually seemed pleased to know I was a reporter, so the man discoursed on economic policy. His view was bright, his mind was still sharp, and I was glad he was working at my old school. I was a loyal alum.

I walked to get a third drink, ate a plate of the shrimp, went to get another. I was feeling good, and the couple was still alone. The man said I reminded him of his son. Was he a reporter, I asked? No, his wife said, a drinker.

My apology was then made and accepted. I don't usually do this, I said, but I seldom see an open bar and I'll be hard at it tomorrow, I promise. She smiled as though she'd heard it before.

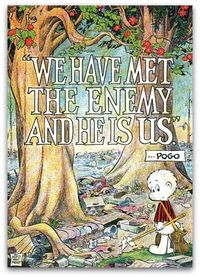

So I told them what troubled me. This boom is doomed, I said. It will all crumble sooner than you think. Oil prices will fall back to Earth, and everyone around us will go broke.

What will happen to the world I inherit, I asked. I felt hopeless, like I was in a car heading toward a cliff, and I felt the man beside me felt the same way.

I told him about a friend. She had recently bought a computer, an S-100 Cromemco it was called, a $20,000 investment that could run four terminals by phone. She was going into the business of transcribing court documents. She could pound out perfect copies of testimony, and charged $1 per page, 50 cents for each additional copy. They printed out next to her, and her employees would send their files along too, to be printed up over night while she slept.

The man seemed pleased, the woman impressed.

I told him about the crowds at ComputerLand. I said the future was in computers, not oil. I said Houston was doomed, this whole world. And I felt good about it.

The room was starting to empty. The cocktail parties of old men don't last that long. I was feeling a little wobbly legged, but youth can correct for that. The older couple was starting to leave, and I followed them out to the hall.

Good on you Dana. It took a while, but you managed a long awaited Bush spasm again!

Good on you Dana. It took a while, but you managed a long awaited Bush spasm again!