The Holy Grail of solar cell researchers, a cell that can be printed by something akin to the ink-jet printer by my desk, is within sight.

The Holy Grail of solar cell researchers, a cell that can be printed by something akin to the ink-jet printer by my desk, is within sight.

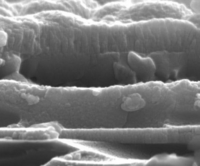

Oregon State University researchers (go Beavers) say they have created CIGS cells with 5% efficiency using an inkjet process. They also sent out this nifty picture (right) of a cross-section of the cell, taken at a micron level.

Their paper, in Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, estimates they can get efficiency up to 12% over time. Naturally a patent has already been applied for.

Most of the publicity surrounding this finding emphasizes the ink-jet printer angle. But there's something more important that must be said about it.

Before we get too excited, let's recognize that there is as-yet no corporate entity involved here, and that further research must be done. We're probably at least five years from a commercial product, at which point there may be other technology entrants.

Still, this illustrates how different solar technology is from computing. With PCs we understood the planar process would dominate by 1971, and we knew what technical hurdles had to be crossed in order to make Moore's Law work. While polysilicon, which is made through a chip-like process, is currently what we think of when we think solar power, a hard, flat panel of solar production on a roof-top, the OSU work is further proof (if any were needed) that's not necessarily the way things will go.

I did a piece for Seeking Alpha on Building Integrated Photo Voltaics (BIPV) recently, and what I found is there's a lot of interesting stuff out there, but there is as-yet no distribution channel for it to reach the market. A printed solar cell, like those contemplated in this research, would have to find its own distribution channel.

But over time, I predict, our view of what and where solar technology exists is going to change. We are going to get solar cells that you print. We already have them. Konarka makes systems based around plastics. The largest American solar cell maker, First Solar, isn't using silicon either, but Cadmium Telluride — their success is based on their ability to scale manufacturing.

So the materials we'll need to produce the dominant solar cell technology is in flux. The nature of the technology is in flux. What solar systems will look like 10 years down the road is definitely up for grabs.

And this is all good news. The more ways we have to harvest solar energy, the more of it we'll harness. We will be able to harness it in our walls, on our electronic devices, as well as on our roofs. My guess is that within 10 years the technology will become cheap enough that cities will be leasing their highway rights-of-way so that companies can erect canopies over them, lined with solar cells, eliminating the "heat sinks" we presently have around major cities.

The world, in other words, is going to change. The face we don't know exactly how that will take place is no reason for being discouraged. It's reason to be excited.

Water Heater by Solar Energy

The solar water heaters can be used for private and commercial. These include solar collectors and storage tanks. There are basically two types of solar water, including active and passive systems. The system is not an active pumping system and control…