Think of this as Volume 17, Number 8 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I've written since 1997. Enjoy.

finance, I have to find new heroes.

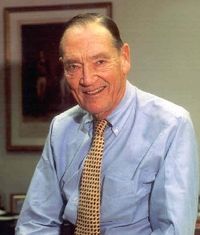

One of them is John C. "Jack" Bogle.

Jack Bogle is sort of the Richard

Stallman of the investing world. He stands on principle, he stands

for the customer, and he doesn't waver.

Unlike Stallman's, Bogle's principles

have made him wealthy. He founded Vanguard Funds. He's retired, but he can't keep himself out of the fray, preaching

the simple gospel that if you put a little away every week, and put

that money into the broad market, your fortunes will rise.

It's called investing.

have a relatively modest pile of what they call “capital,” as I

do now, don't like investing. They prefer gambling. They want to get

in on the next big thing, plunging big piles of cash on something

that will double and re-double and re-re-double in a very short time.

The fact that there are such

propositions encourages them. Every decade brings a new game to play.

When I was a kid, in the 1960s, it was conglomerates. Then in the

1970s the game moved to oil. In the 1980s it was leveraged buyouts,

actually reversing what the smart boys did in the 1960s. Then came

the tech boom of the 1990s, and the housing bubble of the 2000s.

In every case the pattern was the same.

There was a big run-up, there were star companies. Then there came a

crash, and while the best companies in each boom survived the bust,

they were never high-flyers again.

Bogle goes against all of this. Bogle

says you should put your money into the broad market, and keep it

there. Vanguard hired people who would invest this money broadly, and

while they would move money around from time to time, they didn't go

chasing after trends.

be specialty funds. Vanguard created a few. But most of the companies

who created them wanted to sell them. Like the investors they were

chasing, these fund managers wanted to get rich quick, and the way to

do that was to take big cuts of the invested capital. The cut taken

by some funds went as high as 5%, and the limited horizons of these

fund managers made them little better at their work than the

investors they were chasing. Bogle was aiming at returns of 5%, so if

you take 5% out your customer barely breaks even. Vanguard charged

about 1%.

The sharpies promised to take smaller

cuts with the a more recent invention, the Exchange Traded Fund or

ETF. The first such fund, the SPY or “Spider,” came along about

20 years ago and it was a pretty good deal. Like the best Vanguard

funds it bought along a wide front, mirroring the S&P 500. People

who bought it at its launch and are still holding it have seen gains

of 247%, and then there are the regular dividends, which if

reinvested in the fund mean you've done even better. Cash those

checks and even today you're looking at a yield of 2%, better than

with many bonds.

The advantage of an ETF is that you can

trade it just like a stock. You can see its price in the newspaper.

Any broker with access to the markets can take your order, and with

discounters like E*Trade and Charles Schwab (the latter is my own

bookie) offering trades at $10/each and less, it became an easy game

to understand and play. Many companies now offer ETFs – even

Vanguard.

That's the problem. Playing. Bogle, as

I said, advocates buying and holding. You put a little away with each

check, you put it in a broad front, and you go on with your business.

But ETFs encourage gambling, and “specialty” ETFs – based on

countries or market sectors – encourage this attitude even more.

hurt those with the Vanguard attitude just as it did everyone else.

Since Vanguard is relatively passive, its investors were badly

burned, but the point is so was everyone. Those who hung in there,

who didn't cash out and didn't look at their statements, are by now

pretty nearly whole again. But a lot of people couldn't afford that,

and a lot of people are turned off to all markets, including

Vanguard, as a result.

Getting back to the open source

analogy, it's as if open source were being blamed for all the sins of

the market. Because open source advocates base their actions on

belief, they are believers in the ethic of open source, they would be

more deeply impacted by such a scandal. They might come back to

computing more slowly than more cynical customers.

And that's pretty much what has

happened. Since the recovery began in 2009, it has been heavily

dominated by gamblers, rather than investors. Felix Salmon calls them

“hobbyist” investors, and the term is apt. They have what Jim

Cramer, my boss at TheStreet.com, calls “Mad Money,” cash that

might otherwise go into silly hobbies or horses. That's the image

these folks portray – they don't want you to think they're gambling

with their family's savings, and that big losses might hurt those

families deeply.

I benefitted from one of these

mistakes. A relative had to sell hard assets to make up for losses in

the market, and I got a bargain. I like the bargain, but I feel sad

for the relative nonetheless. He never should have gambled. He was a

good steward of the assets he had, and I doubt I can do as well with

them.

84, but he's still on TV, warning that trading ETFs the way you

gamble with stocks is bad business. ETFs are, in their way, better than mutual funds,

but the trading mentality they create with investors is extremely

unhealthy. While most managers play games with how and at what cost

they invest, Vanguard quietly goes about getting the best deal because it's working for its customers, not itself.

The rant on ETFs may wind up being John

Bogle's last lament. I will be very sad when he passes away. He's a

good man, and we need more good men, especially in the arena of

finance, where most believe in the law of the jungle, markets that

are red in tooth and claw. “Nature is cruel,” as Temple Grandin

said. “We don't have to be.”

My best advice to investors is not to

listen to me. I'm a journalist. I'm looking for stories. Instead,

take John Bogle's advice. Put a little away every week, in a mutual

fund company like Vanguard that's looking out for its clients, or in

a mutual life insurance company like The Guardian, which has also

justified its reputation over time. Do business who are working for

you, and don't gamble with your family's future.

Bogle is my hero!

I’ve invested only in S&P 500 funds since 1985 or so when I first got the chance. I was 45 when we retired. I thank Bogle for the best investment advice I ever heard. Bogle likes the idea of only look at your portfolio once a year so you can adjust to have the percentage in bonds the same as your age. Look more often and you only self-inflect stress.

The opposite of Bogle is the snake-oil salesman Cramer. Google some YouTube of Jon Stewart – Cramer. Jon paints him correctly.

Bogle is my hero!

I’ve invested only in S&P 500 funds since 1985 or so when I first got the chance. I was 45 when we retired. I thank Bogle for the best investment advice I ever heard. Bogle likes the idea of only look at your portfolio once a year so you can adjust to have the percentage in bonds the same as your age. Look more often and you only self-inflect stress.

The opposite of Bogle is the snake-oil salesman Cramer. Google some YouTube of Jon Stewart – Cramer. Jon paints him correctly.