Think of this as Volume 17, Number 20 of A-Clue.com, the online newsletter I've written since 1997. Enjoy.

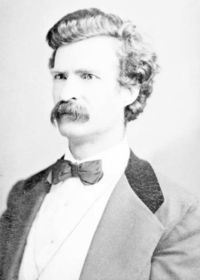

Mark Twain's been gone for over a

Mark Twain's been gone for over a

century now, but his work still leaves a mark.

He was considered America's premier

writer for much of his life, and remains our most famous. He worked

from the unusual position of humor, but produced some of the most

profound classics of the American page.

It's well-known that he liked

technology. He wrote “Huckleberry Finn” on a typewriter, which

was technology in the 1870s. He lost a fortune on a typesetting

machine, which was the minicomputer of the 1880s. He ran his own

publishing house and pioneered the selling of books by subscription.

And he wasn't shy about any of it, which is a lesson more writers

should take to heart.

But what I didn't realize until reading

his autobiography recently was just how much of a technophile he really was.

Because Twain didn't write the way I

Because Twain didn't write the way I

do, or the way most people do. He wasn't really a writer at all. He

was a speaker. He was an entertainer. He was closer to Bill Cosby

than to William Faulkner. The most efficient way for him to write, he

found, was just to say it out loud.

Imagine that.

In Jerry Seinfeld's film “Comedian” we get a good view of what Cosby is like, and what Twain himself was.

Seinfeld and his crew go out to visit the man, who is working in New

Jersey, and come back to their own set to talk about it.

At the time Seinfeld was trying to

build a new 90 minute act following the end of his TV show. It's a

struggle. We see it. It's all written down, it's all well-rehearsed,

and it's typical of how a modern comedian works. Then he sees Cosby.

“He's doing two shows a day, 90 minutes each set, and each one is

completely different,” Jerry says, and the awe is real.

Bill Cosby can just sit on a chair, on

a stage, start talking, and somehow it comes out clean, polished,

complete. There are no long pauses, he doesn't have to reach into his

memory for the next line. He just tells stories, about his life,

about what interests him, and it's gold. All of it.

Twain was like that. From the 1860s he

went on stages around the world and basically riffed for an hour or

two, to tremendous applause. His writing was a cramped, low-tech way

of making his work permanent. I wonder if, had he grown up in our

time, he would have written anything at all.

He wrote by speaking. What came out of

his mouth was amazingly fluent, complete, and graceful. He knew it.

He had an ego, and praise just inflated it. He tried to capture that

in his autobiography by dictating it. Imagine what he could have done

with some tools, like a tape recorder. Imagine what he could have

done on YouTube.

course, and the great Groucho Marx, is that he also brought his pain

to everything he did. It all had heart, like Billy Crystal's best

stuff. In his "Midnight Train to Moscow" Crystal makes a Russian audience laugh for a full hour, then tells a

story about how his great-grandmother supposedly came to America by

telling her family she was going to Kiev by train. He ends it by

getting on a train and seeing that scene, with his daughter playing

the ancestor. Tears your heart out.

Twain, of course, had a lot to be torn

up about. His wife and daughters pre-deceased him. He lost the

fortune on the typesetter. He wasn't nearly as a good a businessman

as he thought – he had this nasty streak of honesty in him.

He felt this pain – all of it – and

it comes out in the autobiography. He knew he wasn't reliable witness

to his own life, and knows no man really is, although most pretend to

be. He struggled with the project for decades, and what finally

emerged from the transcriptions is a man struggling to turn reality

into art.

But the point is that Twain was alive

to all the technology trends of his time. He wasn't cloistered in

some office or library. He was in the world, a participant, and was

constantly pushing the technology envelope to help him deliver more

of himself to his fans.

We all need to be more like that.

Especially our writers.

One caveat on reading the book. The first 200 pages are really only for the academic bibliophile and those retentive types concerned with the provenance of the sources. GO directly to page 200 or so and dive in…you won’t regret it.

One caveat on reading the book. The first 200 pages are really only for the academic bibliophile and those retentive types concerned with the provenance of the sources. GO directly to page 200 or so and dive in…you won’t regret it.