Think of this as Volume 17, Number 32 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

journalism student at Northwestern University, 35 years ago now, I

engaged in debates with my teachers about the coming of the online

world.

They were upset about it. I was

optimistic. I insisted the news business could adapt to a cheaper

means of delivering more product, and the result would be more jobs

for journalists. They insisted the world was coming to an end.

We were both right.

I deliberately sought a career in the

new media, and from the time I joined Newsbytes, in 1985, I looked

for new means through which to get news to people and make a living.

I tried an online newsletter as early as 1989. My Interactive Age

Daily was the first online publication to launch alongside a print

counterpart, in 1994. I treated what became A-Clue.com, from which

this blog post descends, as an online newsletter starting in 1997.

before it was spun. I wrote about a web pre-cursor, the computer

bulletin board, in a 1991 book. I covered what became tablets in

another book, in 1992. I wasn't an entrepreneur – I'm not organized

enough to run a business, nor am I detailed enough. But I could see

the future and moved as rapidly as I could in its direction.

As it turned out, the problem with

newspapers' transiting to an online medium had nothing to do with my

own prescriptions, nor with anything those in the business now claim.

I said that papers should focus on maintaining their reach within the

places, industries or lifestyles they covered. Newspaper people

claimed that “link bait” sites like the Huffington Post were

stealing their ideas, and their readers.

The answer was simpler, and it should

have been obvious to me as a student. The newspaper industry had

become insular and bureaucratic, pretending to be a “profession”

rather than what it really was, a trade and a business.

a newsman, in 1978, was to play the bureaucratic game. You had to

become a political infighter, cultivating internal allies, and

finding a way to keep rivals from gaining a toehold. This meant that

a good reporter without political skills, turned ever-inward toward

protecting his or her bureaucratic rear, was bound to get shit-canned

in favor of mediocrities who knew how to play the internal game.

The result was rot, a steady brain

drain that left the industry focused only on its own comforts, rather

than the desires of readers or the needs of advertisers.

The worst thing the newspaper industry

did was to put people who loved the newsroom in charge of the

business. This was Donald Graham's fatal flaw. He cared more for his

employees than he did for his business. Everyone talks about how he

loved the newsroom, about how he came up through the ranks as a

reporter, from the editorial side. No one realized that, in a time of

rapid change, this insular approach was completely wrong.

Publishers don't share the ethics of

journalists. They have business ethics, which is they get away with

whatever they can. Theirs are the names on the great journalism

schools – Pulitzer, Medill, Annenberg. They're businessmen. They

seek market niches and exploit them ruthlessly. As Mario Batali said

in “The New Yorker” years ago, “our job is to sell food for

more than we pay for it.”

well. Jim Cramer, who founded TheStreet.Com in the last century –

an eon away in Internet time – told a friend once that his best

move was to walk away from the company's management, hiring Elizabeth

DeMarse to turn his company around. This left him free to do what he did

best, entertain the people online and on TV. I wish I'd had a Liz

DeMarse.

Cramer, like Graham, was spending too much time working in his business, not enough on his business. Cramer had the wisdom to realize this and do something about it.

It's DeMarse who will get her name on

the journalism schools of the future, not Cramer. But in all the

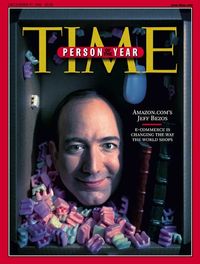

boo-hooing over the fate of Graham's Washington Post, which was

finally sold (for more than it was worth) to someone who actually

knows something about business, the chattering classes refuse to

consider that they may be the problem, not the solution.

pennies on the dollar, but being sold at last to people outside the

industry, we'll get to see what's what and who's who in local

journalism again.

The fact is we now have working

business models for online journalism. Let me repeat that – we have

working business models for online journalism. We even have an

editorial career path.

You start by picking your beat,

studying it closely, and blogging about it. On your own. It's free.

You don't get a job anymore by beating down editors' doors. You get

it the way I did, by doing the work. I did a magazine story in

Houston in 1978 that my editors' boss showed him after my third

attempt to gain a foothold on the staff, telling the editor “see if

you can hire this guy.” (The editor told me later he hid my resume

under a stack of papers, nodded sagely, and said he'd see what he

could do.)

The job equivalent of hanging out at

the police station or courthouse is to do “link bait” stories.

That's how you get your writing chops, it's how you get up your

typing speed, it's how you learn to think on your feet, and these are

the skills that count in this new medium. Some of those skills come

from TV, especially the ability to improvise, and some come from the

whole business of writing for a living. Others – the ability and

willingness to use others' work as fodder for your own – are

generic to this medium.

this way, a budding online journalist has to learn to use social

tools to publicize work, avoiding flame wars and building their own

reputation, not just that of the employer. It's only after this is

accomplished that you'll get the time and space to pursue long-form

stories. These do sell, they sell well, but they're not the whole

online paper, anywhere, and never have been. It's only after proving

yourself on features, not just as a reporter who can husband time by

leaving the office only after the Web has failed, but as a

storyteller, that you should get a shot at stardom.

In the absence of people who've come up

through the ranks in this way, we're settling on in-house “experts”

for entertainment, people who've been part of the beat. Whether it's

sports stars on ESPN, or investment bankers on CNBC, or politicians

on CNN, today's talking heads and digirati are only stand-ins for the

kind of people we need in the future. You can become that person by

devoting yourself to your personal brand, to your own beat, and to

learning the skills you need, one by one, to take over from these

asshats.

Publishers, by contrast, focus on other

things. They don't care about the newsroom, and they only

the product insofar as it hits the target, winning share and loyalty

within the place, industry or lifestyle they serve. And that is the

job – serving the industry, the lifestyle, or the place where the

publication lives. Never forget that. Intrinsic targeting, targeting

ads based on algorithms using data about readers, hasn't worked and

won't work. Extrinsic targeting, targeting ads based on the place,

industry or lifestyle the site in question is covering, and that the

reader is caring about at the moment they're reading, is still what

counts, even in the 21st century.

Your job, as a publisher, remains what

it was in the 19th century. Define a market, aggregate

both the buyers and sellers, and stimulate financial transactions

between them. Publishing is a market-making proposition, and those

who create the best marketplaces win. Every time.

These are still the early innings of

the online publishing game. The collapse of newspapers is a gift from

above, not a plague. It opens up vast new opportunities for people

who have learned their business, publishers and editors both.

I wish I were 35 years younger.