Think of this as Volume 17, Number 45 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

feel rejected. When you feel rejected, you predict disaster. When you

predict disaster, you dump everything for gold or Bitcoins. When you

dump everything for gold or bitcoins you feed a disaster. When you

feed a disaster you get a disaster, but not the kind you want.

There is a growing chorus predicting

imminent disaster for the U.S. economy. They see the dollar becoming

worthless, or stocks becoming worthless. They see the economy falling

into a black hole.

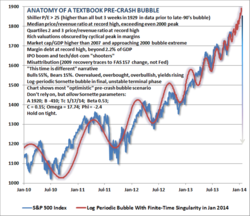

keeping the stock market rising. In fact, stocks are greatly overvalued, in relation to other asset classes. That's not a bug in our present

policy, but a feature.

What we have faced, since 2009, is

basically a strike by big money. Trillions of dollars are sitting in

vaults, unused. The purpose of global banking policy is to break the

strike.

Strikes are traditionally broken by

employers bringing in new employees, called strike-breakers. Bankers

are trying to break the money strike by creating new money, and

seeing that money get a return, to force money on strike to pay a

price for staying off the job.

This brings us to the basic question of

what's money. The apocalyptic crowd thinks that all money is money,

that all money is created equal. It's not. Only money that is

employed is money, only money that's working, in the market place,

trying to create value, is really money. The other money, whether

parked in a vault, in cash, or in Bitcoins, is just potential money.

Aladdin's Cave. What were all those jewels, all that gold, doing while it was in the

cave? They weren't money. It wasn't visible to the rest of society.

The Baghdad markets went on as before. They did value gold and jewels

very highly, because there was not much to trade. But the economy

kept rolling.

What happened after Aladdin returned to

Baghdad, with all those jewels and all that gold? At first, it was a

stimulus. But the economy quickly adjusted, and the value of gold and

jewels fell precipitously. A wise Aladdin might try to keep much of

his hoard out of the market, spending it slowly, as the economy

caught up. But it would still be the economy that defined money, and

the value of jewels or gold. And there would be constant downward

pressure on the value of jewels or gold, as traders would know a

great hoard was out there and might be sprung onto them at any time.

and gold in this case represent money on strike, money sitting in

corporate vaults, money that's not in the economy. The value of cash

is not depreciating, even as central banks pump more-and-more cash

into the economy, because much of that cash is going into assets, and

not going to work.

Stocks are just highly fungible assets.

They're not always “risk capital,” as CNBC insists. Not all money

in stocks is “going to work.”

That's because the treasurers who

control the biggest stocks don't need the money. They have more than

they need. They don't want to put people to work: they're part of the strike. So what do they do with it?

They have two choices:

- When a company like Apple holds

hundreds of billions of dollars in cash, it doesn't really need to

sell stock to keep going. It buys back stock. It may pay a

dividend. It's encouraged to, in essence, give the cash back and

keep it moving. But it doesn't. - Berkshire-Hathaway holds $40

billion of cash. It's such a big pile that Berkshire-Hathaway has

been buying whole companies, operating companies like Heinz.

Berkshire-Hathaway, the reporters claim, is putting its money to

work.

stock. It's the more common course. That action, repeated hundreds of

times, drives the limited amount of stock in circulation higher in

price. Berkshire-Hathaway's action, while more noble, has the same

effect. When it takes out whole companies, it too reduces the amount

of stock available to buy, and drives the price up.

High stock prices, in short, are a

product of underemployed money. If money were pulled out of vaults

and went to work, if it really went into new, risky ventures, the

relative value of stocks would go down.

doing? They're sticking money into the equivalent of mattresses,

buying things like Bitcoin. They're talking up gold. They're doing

anything but keeping their money employed. They're joining the

strike.

It's a mystery to these people how

currencies can remain valuable with central banks continuing to pump

out more money. Simple. Much of that money is joining the strike,

because the money is going to the wrong people. It's going to banks,

and going to rich people who already have money.

The best way to break the money strike

isn't for government to issue money. It's for government to put money

to work, for government to spend money, putting people to work who will then spend the money. But the Armageddon caucus has used politics to close

off this solution, crying “debt debt debt,” forcing unprecedented

amounts of austerity on global economies as a result.

That's not entirely bad in the long

run, but in the long run we're all dead. It's ridiculous in the short

run.

Back in the early 1970s, Richard Nixon

said “we're all Keynsians now.” It was assumed that fiscal

policy, manipulating public debt up when the economy was poor, down

when it was doing well, was the only way to run a country. They were

challenged by Milton Friedman's monetarists, who saw the money

supply, run by central bankers, as the key to growth. They believed

solely in monetary policy.

Austrian economics, which holds that depressions are good, that they

teach a lesson, and that fiscal policy is a horrible tool for

managing economic growth. This is what those preaching Armageddon

believe in, believing in Hayek as firmly as workers 100 years ago

believed in Marx. This has left us with just one tool, monetary

policy, pumping out enough money to end the money strike, and it's

not a great solution. It's just the only one we have.

Spending money, putting money to work

in the form of public works or driving economic change, would end the

money strike. Borrowing the money that is unemployed and forcing it

back to work would, in time, break the money strike and cause stock

prices to fall. So would forcing up costs by raising minimum wages.

This would take money out of the hands of the strikers and put it

into the hands of people who will spend it.

The Armageddon caucus doesn't see how

their very actions are keeping the stock market bubble rising. They

think that, if enough money goes on strike, the stock market fever

will break. They think there's some arbitrary value at which stock

prices have to “crash.” But bankers won't let the money strike

succeed. They will keep pumping out new money, feeding cash into the

economic car.

Which brings me to the final irony in

all this. It's policies defined as “liberal” that will break the

back of the money strike, and drive the stock market down. Borrowing

and spending, the use of fiscal policy, a policy opposite to the one

the Armageddon caucus favors, will break the money strike and pop the

stock market bubble.

a lot in common with the 1970s. This time, our politics, has much in

common with it. The 2010s are a fun-house mirror held up to the 70s,

a sort of bizarro version of it. Back then people thought you could

spend your way to heaven, and of course you couldn't. Today people

think that monetary manipulation is the way to heaven, and of course

it isn't.

What works is balance. What works is

the use of both monetary and fiscal policy, in tandem, to reduce the

impact of speculation and keep economies rolling, to empty Aladdin's

cave without crashing the value of jewels and gold.

But our economic debates are equipped

today with ideological blinders, ignoring the complexity of reality.

And against this stupidity the gods themselves contend in vain.

At this point, with some much cash idle and such a low tax-to-GDP ratio, even a modest tax specifically on hoarded cash would eliminate the deficit, provide a continuing revenue stream against the debt and stimulate real economic activity. And that common-sense idea would have a zero-percent chance in this Congress.

Unrelated, but heard this on the Bloomberg, I think from Scarlet Fu: peak shale. Scared the crap out of another news talker.

At this point, with some much cash idle and such a low tax-to-GDP ratio, even a modest tax specifically on hoarded cash would eliminate the deficit, provide a continuing revenue stream against the debt and stimulate real economic activity. And that common-sense idea would have a zero-percent chance in this Congress.

Unrelated, but heard this on the Bloomberg, I think from Scarlet Fu: peak shale. Scared the crap out of another news talker.

I’ve heard this talk of “peak shale” too. Just another tool to try and keep the price up.

A tax on hoarded cash might be a good thing to have, but you can’t tax cash that’s not in the country, and that’s where it is. It would be like England putting a tax on money English people hold in America. Wouldn’t work. Thus the idea of an incentive, a full or partial “amnesty” for bringing money back, has been floated.

I’ve heard this talk of “peak shale” too. Just another tool to try and keep the price up.

A tax on hoarded cash might be a good thing to have, but you can’t tax cash that’s not in the country, and that’s where it is. It would be like England putting a tax on money English people hold in America. Wouldn’t work. Thus the idea of an incentive, a full or partial “amnesty” for bringing money back, has been floated.