Think of this as Volume 17, Number 52 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

While in New York recently I got a powerful insight into what the next year will bring.

I decided to visit the site of the World Trade Center, “Ground Zero,” or “The Pit,” as it's been variously called.

Construction is transforming it. The new One World Trade Center, with its huge antenna, has been topped out. A shorter building, called Four World Trade Center, is going up nearby. The buildings that survived 9-11 are being redone under the name Brookfield Place .

Right now, a visit remains like going to a grave site. There are tickets, and tours, of the site where the Towers once stood, now transformed into a memorial. But there is also scaffolding everywhere, and it obscures the view of what's actually happening, the beautiful process of rebuilding.

Next year, that scaffolding comes down. Next year, New York can begin the important process of forgetting.

We all talk about remembering the past, of memorializing it, but it's also important to forget it and move on. You can't mourn forever.

Some time next year, New York will finally start to move on, and so will the rest of us. Instead of the empty, elevated courtyard of the old site, the new site is at street level. The new World Trade Center isn't separated from the rest of the city, as the old one was, but is integrated into it.

Moses transformed the city, turning neighborhoods into “projects,” cutting through others with freeways, always obsessed with “the flow” of traffic, with the getting-to as opposed to the destination.

I never went to the Towers in life. As a child I'd read something, I think in The New York Times, I think by Ada Louise Huxtable, complaining that the design approved for those buildings could “pancake” if a hot-enough fire hit the upper floors, which is precisely what happened when two jet airliners were crashed into them on that horrible day. They fell into their own basements, as in a controlled demolition, rather than coming down on adjacent neighborhoods and killing even more people.

This is the point we're at in the larger cycle. For 2014, we're playing the 1974 game, the 1938 game, the 1902 game, or the 1866 game, depending on which crisis you're comparing ours to. Each was a year of forgetting the past and moving into an uncertain, different future, with a new set of political principles in place and a new governing majority.

Following each generational crisis, a new political dynamic sets like concrete, a new set of myths and values are created to define power. The speed with which this happens can vary. It's happening more slowly in our time because our transition has been relatively peaceful, unless you count the low-scale civil war being waged by the NRA against everyone else.

-

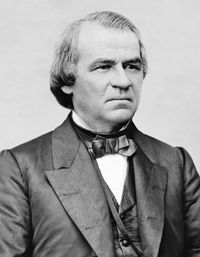

By 1866, the Civil War was over and Reconstruction had begun. There was still a battle being fought in Washington, which would culminate in the impeachment of Andrew Johnson (right), but the actual fighting was over, and the course of Republican domination, and Democratic retrenchment in the face of “waving the bloody shirt” against reform, was set.

-

By 1902, the Progressive Movement was well underway. Theodore Roosevelt was President, he had the wind at his back in the wake of McKinley's assassination, and the reform of the era known as “Ragtime” was in the air.

-

By 1938, Franklin Roosevelt had been President for as long as anyone could remember. The Great Depression was receding into the background, the Small Depression was sinking in, but attention had turned to the larger crisis of World War II, the challenges of Fascism and Communism to the existence of democracy and of capitalistm itself.

-

By 1974, we were in the middle of impeaching Nixon. The Vietnam War was winding down, the headlines dominated not by the Far East but by the Middle East. The Oil Crisis had begun, “stagflation” was the word of the year, and the suburbs were preparing to rise in the revolt that would eventually bring Reaganism to complete the work Nixonism began.

In 2014, it appears that the crisis isn't even over. Washington-based hacks all predict Republican gains. They see the President as weak, Congress as hated, and assume that the voters will back conservative “reform,” a return to Reaganism, to Bushism, and the policies lying beyond them.

They don't know jack.

It is beginning to dawn on people that if everyone shows up, Democrats win, a view reinforced by Democratic victories in Virginia. The Republican response is not only anti-Democratic, but profoundly anti-democratic, and the harder it's pushed, the harder will become the response of the new majority, which is only growing with time, as voters who switched for Nixon in the late 1960s die off, and as those born since 1990 grow in number, pushing politics to the left.

That's the macro-view, the 30,000 foot view, the verdict of history on our time. From ground level, many reporters still can't see it, since most came of age, and came to the city, during the Clinton era or the Bush era, when the wind blew the other way.

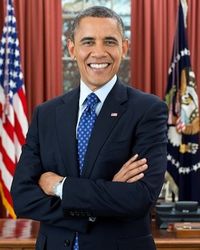

But the President knows which way the wind blows. That's why he gave such a moving address on what he called “Economic Mobility” (and critics quickly dubbed “inequality”) on December 4.

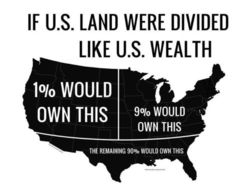

We’ve got to move beyond the false notion that this is an issue exclusively of minority concern. And we have to reject a politics that suggests any effort to address it in a meaningful way somehow pits the interests of a deserving middle class against those of an undeserving poor in search of handouts.”

I don't think you can have a better summation of the Obama Thesis than that. Those who support only the interests of the 1% are outside the consensus.

Each new generation's thesis begins with a key challenge. To our nation, in Lincoln's Day. To economic progress, in McKinley's day. To democracy, in Franklin Roosevelt's day. To order, in Nixon's day.

This is our challenge, maximizing the value of our human capital, which in the Age of the Internet is the kind of capital that counts most.

None of this will be settled in 2014, but as time passes we learn to forget the past and focus on the future. This is what our children will begin their life's struggle for. Only when we're united, only when all our human capital is engaged, can we have any hope of heading off the destruction of all life, caused by man's past successes, that is heading our way.