Think of this as Volume 17, Number 50 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

I asked it for a simple reason. This is the world we're living in. When I first became a computer journalist people like science fiction author Jerry Pournelle were among the few predicting such a thing could happen, and he was such a speculative writer few people took him seriously.

But he was absolutely right, down to the year – the year 2000.

Now that it's happened, what happens to education? What should we be teaching, and how should we be teaching it?

Last week I offered two basic answers – teach people to read what's online and understand it.

Today I want to look at three more.

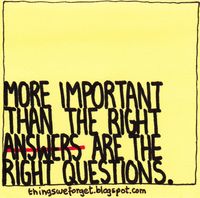

Asking The Right Questions

These are often different things, and whenever you use a search engine like Google you find that out again. You can type a question, any question, and get a million different answers. But if that question is really a good one, chances are you won't find the right answer on that first results page.

Google isn't the only interface. Interfaces will change. The way our kids try to act upon the vast database before us is going to change, again and again and again. They need to be equipped with the skill of getting the answers they want, not just the answers they're given.

The right question, it turns out, isn't one question. It's a set of questions, which go around the subject you're studying and build a story. It's inside that story that you'll find the answer. That's something I've learned from doing thousands of interviews, and using the Internet to do thousands of stories, over many years now.

Is anyone teaching this skill today? No. Some university programs are approaching it, in various ways, depending on the discipline, but this is a general talent that every educated person needs to have. Just as it was once important to know how to use a library, it's just as important now to use the Internet well, to ask it sets of questions, and get the story you need out of it.

Then, cycling back to last week's Clue, you need to learn how to write it. Clear, concise, expository writing, the kind I've been trying to do all my life, is a key Internet skill.

Whether you're ultimately telling your story through words, sounds, pictures, or video, it's always going to start with words of some kind. It always starts with a story. So as important as it is to learn how to ask good questions, you also need to learn how to express the answers in a powerful way, to tell a story.

Curating

I'm a polymath – miles wide and an inch deep. We need experts who have deep knowledge of small subsets. That's something anyone can seek to do and seek to be.

Curation is a difficult subject, and not one I've mastered. I will frequently curate for a story by collecting links as bookmarks, but those get lost when I go on to the next story. For years I would collect files on stories, put those files into drawers, and then find myself throwing out those drawers a year or so later, only to have to re-learn some of those facts again.

Of course, I was lucky for two reasons. The Internet left those drawers open, and searchable, over time. More important, the woman I married turned out to be a great curator. She has been a success at her job, in part, by being a curator, someone who could find out what was said about something a year or even five years ago. Some of it she pulls out of her head, but more of it she pulls from well-organized files.

She does the same thing at home, and I don't exactly know how she does it, except that she spends a lot of time on it. She organizes our money, so our accountants can do the taxes quickly. She organizes our stuff, so I can pull out the manual for something we bought in 2006. She's just organized.

How do you teach organization, of files, or of your own computer, soon to be your own cloud? How do you make sure that you can pull the answers you want from what you collect?

Then how do you do that mentally? How do you organize a collection of notes, not into a story, but into a whole book? How do you do that?

Teach me. And teach that to your children. Because they're going to need it, no matter how good the unstructured search process becomes. You can become indispensible in any field simply by curating it, you can build a career even in the 21st century by being the world's leading expert at something and making yourself available when someone needs that expertise.

Contributing

What we're teaching, instead, is thou shalt nots. We're telling kids to be just as afraid of the online world as they are of the offline world. This is stupid beyond stupid. How are they going to learn anything outside themselves if they can't talk to strangers? Strangers may just be friends you haven't met yet.

It's the lack of skill in adding to the Internet, and the lack of adequate teaching of Netiquette, that has led to the rise of Snapchat. Not that there's anything wrong with Snapchat, if you have a private message you don't want saved. But kids are using it to keep themselves, and the rest of the world, stupid.

The whole process of building an online reputation, of engaging properly with other people and ignoring the trolls, isn't taught in schools. Teachers are completely at sea on this question, because it's not something they've learned themselves. It's something which, in a way, we're all learning together, both the young and the old.

Through 30 years spent online, I've gained some minor understanding of it. I always use my real name when I'm online, and since I'm the only one who has it I feel pretty comfortable defending it. But I'm a journalist. I'm meant to live in the public eye. I was taught from the start of my working life to live as though I were on TV all the time, because in some ways I would be. My reputation would be out there, my credibility account would be visible, I was taught, and so I have tried to act – not always successfully.

Treating others with respect, treating yourself and your desires with respect, forgiving yourself and others, as you would have them forgive you, are skills that can only be learned over a lifetime. But they can also be taught, and need to be, along with all the other lessons of Netiquette that need to be part of every child's education.

This has been a long Clue, but it's just a Clue. It's not the whole story. The whole story is still being written, and rewritten, by you, and by millions of others. How will our children make their way in such a world?

Teach them as well as you can, and then let them try. They won't disappoint. As Mark Twain wrote, "Dream other dreams, and better."

Another excellent article Dana… you continually search for and find jems!

Stephen Hoyt

Quebec, Canada

Another excellent article Dana… you continually search for and find jems!

Stephen Hoyt

Quebec, Canada