Think of this as Volume 18, Number 13 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

In the case of America, which has been a united nation for most of 225 years now, it can rhyme multiple times.

The Crisis of 1896, which resulted in the Progressive Era, rhymed in many ways with the first political crisis in our history, the dispute between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson resulting in the 1800 Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican victory over Hamilton's Federalists.

The dispute in both cases was one of basic finance. Hamilton wanted a strong central government, and a national bank, in order to grow manufacturing and assure that the new United States could defend itself. Jefferson sought a “republican” government, a full democracy in which all men could be treated equally because they were equal.

Equally poor.

Reading Jefferson's own words from the 1790s, it's clear that what he objected to in Hamilton was less the means to his end than the end itself. That end was prosperity. Hamilton wanted America to become rich, and worked to create institutions aimed at doing that. Jefferson cared less about money than about rights. He believed money corrupted, that it was responsible for the injustices he'd seen in France.

Jefferson feared Hamilton was aping Great Britain, whose great banks had created a rich empire, mostly benefitting its great men. In this he was right.

When the germs of this crisis repeated themselves in the 1890s, Democrats took the side of Jefferson and Republicans that of Hamilton. Democrats focused on rights and equality, Republicans on economic progress from which reform might be built, leveling the playing field a bit, and creating the kind of social mobility needed to maintain support for the system.

The current crisis is a test of both our economic system, which Hamilton did so much to create, and the political assumptions birthed by Jefferson. Whenever you see someone talk about “limited government,” they are hearkening back to Jefferson. We need to remember that while Jefferson sought limited government, he also sought a limited society, and a limited economy. It's wonderful rhetoric, but it can be absolutely awful economic policy.

The same thing is happening throughout society. Luke Russert is a Washington reporter because his dad was. Ronan Farrow is a star because his mom was. Barry Bonds is the son of Bobby. There are countless other examples.

Sometimes, the sons or daughters of great men and women can equal or top their parents. John Quincy Adams did. I would argue that John Huston was a bigger figure in Hollywood history than his father Walter, the actor. But did George W. Bush? You'd have to be an idiot to think so.

Problem is, America today is filled with idiots. It's filled with people who haven't actually read books like Jefferson vs. Hamilton, people whose “history” and “precepts” are merely what they were spoon-fed by a media run by the ultra-wealthy, on behalf of the ultra-wealthy.

The Confederacy was a threat, not just to the Union, but to democracy itself, because a minority was controlling the country. The Progressive Era was, like the present age, about the limits wealth must face to maintain a free and democratic polity. The New Deal was followed immediately by the false choices of Fascism and Communism. Vietnam was about maintaining order against a generation that seemed devoted to disorder.

The current crisis has things in common with all these previous crises. Like the Civil War, it's concentrated in one region, the South, or more precisely our rural precincts, the same crowd that rose with William Jennings Bryan as Populists. As with the New Deal era, and the Vietnam era, there is a real question about whether democracy can survive in the face of both outright opposition to it and cynicism born of profound, honestly-derived disappointments.

But it always comes back to democracy, the right of the majority to rule, the requirement that minority rights be respected, the needs of the whole vs. the needs of the individual, a system that can balance all these things and constantly re-adjust that balance in the face of time.

As with earlier crises, the result of a single election doesn't tell the tale.

The answer lies inside our Crisis Leader, but it also lies beyond him. It is absolutely normal that, five years after a crisis comes, we're getting pretty damned tired of the crisis, and anxious to move on.

By 1866 Andrew Johnson was President. By 1902 Theodore Roosevelt was President. By 1938 Franklin D. Roosevelt was at the low ebb of his popularity, and in 1974 Richard Nixon resigned after being impeached by the Hosue.

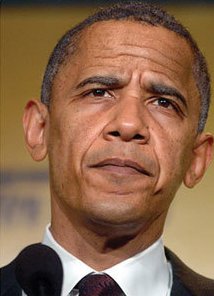

So it's not surprising that Barack Hussein Obama is unpopular, that he's widely ridiculed, and that the specifics of his policy-making have drawn not just opposition, but widespread public wrath.

But it's vital, at times like this, to understand that Obama is just the vessel of democracy. He's not the answer. We're the answer. We chose him in a time of crisis for good reasons, because our system of self-government, the legacy of Jefferson, and our economic system, the legacy of Hamilton, were under imminent threat.

During an era of crisis you need to keep your eyes on the prize. Not utopia, but hope, and real change.