Think of this as Volume 18, Number 14 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

When the business day begins, thousands of well-off people turn on their TVs to Squawk on the Street or Opening Bell, its Fox Business equivalent.

When the business day begins, thousands of well-off people turn on their TVs to Squawk on the Street or Opening Bell, its Fox Business equivalent.

They think they're learning how to get rich. They're thinking they're learning what money is doing.

They're wrong.

What they're seeing is a TV studio surrounded by displays for what is, in the end, just the very tip of the financial market iceberg.

Trading does not really happen on the New York Stock Exchange – TV happens there. And the stock market represents only a very small portion of the financial market.

You're not even seeing what happens in the corporate world. In this decade, private capital takes far more of the profit out of corporations than traders ever get to see. Private capital starts up companies, and their capital grows them. Most often, the companies resulting from this process are sold on to large, public companies, like Google or Facebook. The public never even gets a taste of what's being created.

You're not even seeing what happens in the corporate world. In this decade, private capital takes far more of the profit out of corporations than traders ever get to see. Private capital starts up companies, and their capital grows them. Most often, the companies resulting from this process are sold on to large, public companies, like Google or Facebook. The public never even gets a taste of what's being created.

It's worse. Down deep in the bowels of the market, where the less-attractive stocks play, private capital is constantly busy buying up public companies, dressing them up, merging them or de-leveraging them, and passing them onto the public as gilt-edge opportunities. Companies like CBS Outdoor, one of the latest to go public, are like that – they're private equity crap that's put on a plate and called fois gras.

Even the market for stocks is just a tiny piece of a much larger market. Commodities are the thing these days. Everything is a commodity, from the loan you took to buy your house, to the dollars you use for your mortgage payment, to the materials which went into the house and the house itself.

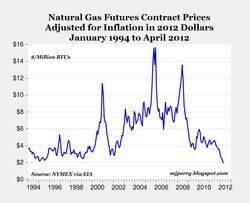

Commodities are hot because, unlike stocks, commodities can be leveraged, they trade very actively, they can give you a fat return or wipe you out in the time it takes a fat finger to press a key.

Now remember that most future contracts are leveraged, by their nature. A trader may just put out a few thousand dollars to control a much larger collection of contracts. Thus, small changes in the price of the underlying commodity – more precisely the expected price of the commodity at some date in the future – is delivering big gains or losses.

It's not even traders who are doing the trading. Mostly, it's algorithms. Software defines price ranges, it defines when to get into or out of a trade, and the people are either watching screens to make sure the software works or doing customer service.

You may have just a few thousand dollars invested in a trade, but you're playing on margin, so a change of just a few cents in the expected price of natural gas can make your fortune or wipe you out. Think about it this way. The minimum contract is 5 times your annual natural gas bill, and hardly anyone is playing with the minimum. These are big boys playing with multi-billion dollar chip piles.

Before you start thinking I don't like such games, please understand that these markets have a legitimate purpose, and are far more important to the functioning of our economy than the New York Stock Exchange.

Schools or transit systems can use futures contracts to lock in a sustainable price for an important commodity. At the same time producers are getting the best, fairest price for what they have to sell. In the end, things do get sold, at a price that's the product of dozens of trading days. Having a well-capitalized market means those who need commodities can know their costs with confidence, and can plan in advance.

There are futures markets for all kinds of commodities, even the currencies used to buy such commodities. Currencies themselves are just commodities. The reason Bitcoin makes no sense right now is not because it's theoretically stupid, or not backed by government. It's the fact that it's so thinly traded you can't set a reliable price for it – it's purely a speculative instrument.

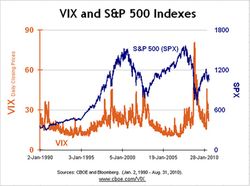

The world's big financial institutions aren't mainly engaged in trading stocks and bonds. They're not mainly interested in making or collecting loans. They're trading these kinds of futures instruments, sometimes for clients or (more dangerously) for their own accounts.

Again, the trading is legitimate. Having your costs locked-in allows for planning. Getting the best price allows for planning. Laying-off other bets through futures is a form of insurance, and insurance is a very good thing (even though as I've said mainly times you're betting on disaster when you buy it, and betting against it when you sell it).

The financial game is a very good thing. But unless it's played honestly, unless double-dealers go to jail, ordinary people won't trust it and won't trust the system it has created.

The cost of recovery has been to paper over trust in our financial system, and to restrict the gains it creates to a very, very small number of people and institutions with the money to play the leverage game. Can you really say that, faced with a choice between the 33% unemployment of 1933 and what actually happened, you would have done differently than the President did?

I can't.

But if we're to restore confidence in the great financial edifice, we need the equivalent of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Tell the truth, tell all of it, and gain immunity for what you did. Refuse, and all the weapons of the law will be used to hunt you down and punish you. Really punish you, not just by taking some of your money but all of it, and that of your family, as well as throwing you in jail to rot for the rest of your life.