Think of this as Volume 18, Number 18 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

The NYSE was founded in 1792 under a buttonwood tree, and to most people it represents the very essence of money and trading.

ICE was founded in 1999, and has its offices off Powers Ferry Road at I-285, about 10 miles from my home and 2 miles from my wife's offices.

ICE is basically a transaction processor. The transactions they do make markets in currencies and commodities. They actually bought ICE for one of its derivatives markets, called Liffe.

The difference between the stocks you buy and what's offered in these markets comes down to one word: liquidity.

Take the most popular ICE contract on oil, for so-called “Brent North Sea” futures. It starts at 1,000 barrels. Market participants can hold as many as 3,000 of these contracts at one time, essentially controlling 3 million barrels of oil at once.

On May 2, ICE traded 567,070 of these contracts, and there was open interest of 1,492,608 contracts. That’s a lot of liquidity, 1.5 billion barrels worth, more than $150 billion, which can move about .75% in any one day.

Thus, if you buy a single contract, and hold it for a day, and you’re wrong on the market’s direction, that’s a move of over $75,000 – 1,000 barrels, at $107/barrel, moving just 75 cents.

There are only two reasons to play this game. Either you’re a participant in the market – a refinery trying to control its costs, a major producer looking to get a price – or you think of $75,000 as sofa cushion money.

Other markets created by groups like ICE, such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which makes a market in wheat futures, offer similar opportunities for gain and loss. They’re for serious players only, committed either through capital, supply, or need for what’s being traded.

I had a cousin in Texas once who speculated on commodity futures. He thought he had a handle on the fundamentals, and he probably did. But short-term moves, driven by emotion and market momentum, wiped out his risk capital, and more. Relatives bought his land, which had come down from grandparents, to keep it in the family.

But the lesson was learned. At least by us. And it should be learned by you as well.

Why am I writing this?

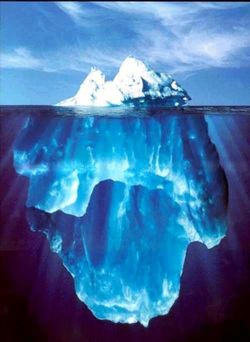

People with billions of dollars on the line may not be “manipulating” the price of your Amazon.Com shares. They may just be playing some other game – oil in the spring, natural gas when it’s cold, wheat during the summer – and leave the market you’re in high-and-dry, ready for a fall that has nothing to do with the real value of your asset.

Traders play fear with the VIX, they play the Russian Ruble, they even make money going long a 2-year treasury note, because they have enough leverage and capital to play in these markets. They have fat fingers, they have stop loss provisions that can get them out of bad positions quickly. These are professionals.

Many big institutions, like Baring Brothers, have been literally destroyed by rogue actions of single traders. The whole point of making companies "too big to fail" may be to handle these kinds of losses, and accomodate these kinds of trades.

Which means that, barring global regulation, the trades and bets are just going to get bigger until we all go over the falls again. Traders in these markets can be as emotional and stubborn as any Texas rancher or day trader shorting Amazon.Com.

So what’s an investor to do? Stick with what you know, don’t plunge into shark-infested waters, and don’t bet more than you can lose. Buy when the tide is out and sell when the big boys get ravenous for what you have.

Stay with stocks.