Think of this as Volume 18, Number 23 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

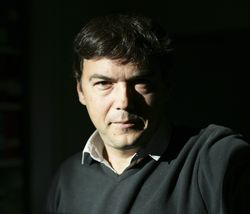

A lot has been written about Thomas Piketty's “Capital in the 21st Century.”

A lot has been written about Thomas Piketty's “Capital in the 21st Century.”

The bulk of it either objects to Piketty's conclusions or comes from people who haven't read the book.

I have read the book. It's as good as they say. But the point isn't in its conclusions. The point is in its methodology. It's how Piketty drew his conclusions that makes this the most important economic text of the century so far.

Quite simply, Piketty used data. Piketty gathered economic statistics going back over 200 years, during the course of a 20 year study. He analyzed this data using powerful computers that now sit on a desktop and may not have existed in 1990.

Some of its data is of poor quality, especially what comes from the 19th century. But it's the best data we have. And those who would challenge his conclusions should start by gathering more data. He'd like that.

Some of its data is of poor quality, especially what comes from the 19th century. But it's the best data we have. And those who would challenge his conclusions should start by gathering more data. He'd like that.

Piketty's analysis is possible only because of today's cheap, powerful computer hardware. When this kind of analysis moves to the cloud, the number of insights available should multiply exponentially.

Another point. Some of Piketty's data is of high quality, especially that based on income tax receipts in developed countries, starting with the passage of the 16th Amendment in the U.S. a century ago. Income tax receipts, it turns out, deliver a wealth of data about the wealth of nations.

Piketty's book thus creates a great new objection to proposals for a so-called “Fair Tax,” which would replace income taxes with sales levies. Eliminating the income tax eliminates the data. It renders policy makers blind. That may be the intention of the plan's sponsors, and those sponsors now need to answer for this effect.

But I digress.

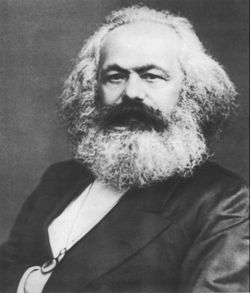

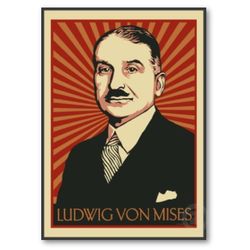

Before the present time, economics was entirely theoretical. Marx didn't base his theories on data, and neither did the Austrian School. They created models out of crude observations and said, “this explains it.” But models can't really explain data in the absense of data.

Piketty sticks the final fork in both Marx and von Mises. Such arguments, no matter where they lead, are pure bullshit in a world defined by hard data.

Piketty is the first economist to try and model entire economies using data. You can argue that he “cherry picked” his data but you are then under an obligation to bring your own data to the party. The usual way of “fisking” someone whose arguments you oppose won't work.

But if you attack those conclusions without seeking out your own data you're not arguing economics any more. You're either playing on Piketty's field – depending on his data to argue against his conclusions is a losing game – or you're rejecting the use of data entirely. You're arguing against the science he has brought to the field.

When I was studying political science in the 1970s, the field was in the first throes of its own battle with data. The data in question was the survey. Questions would be asked of various sets of people, and statistical analysis was then used to draw conclusions from the results. Instead of talking about politics, political scientists found themselves arguing over the validity of various surveys. They were in a new field and many didn't like it.

But in the end what makes the difference between the liberal arts and the sciences is data. Before Piketty economics was an art, an art based mainly in math but an art nevertheless. What Piketty's book has done is demand that, in the future, economics be based on science, and scientific method.

In fact, Piketty's response to his critics was given in a language economists and political scientists still don't comprehend. “My historical data series can be improved and will be improved in the future,” he said. In other words, if you want to argue with me, argue from data, not polemically.

There is a second challenge to conservatives in Piketty's conclusions, one I've yet to see a comprehensive response to.

That is, the greatest force for economic equality turns out to be war.

Those who support economic inequality, it turns out, should be pushing for peace, and those who wish an end to it should be pushing for war. This is opposite to the politics of our moment. Conservatives tend to support a strong defense, high military budgets, and action against political enemies from Venezuela to the Middle East to the Ukraine. It's liberals who support lower military spending and who want to limit America's intervention in the affairs of the world.

War, it turns out, is good for something. Just nothing that conservatives support. And peace, it turns out, produces economic results that liberals loathe.

The answer to these questions, in my view, is simple. Get more data. Open source the data, so economists of all stripes have cheap access to it. Make people argue from data, and you will transform economics.

Piketty's book is the first step toward a new “science” of economics.

There’s no reason I can see that it would have to be spending on war–because it’s plainly the spending that’s operative here. And who spends on war? Governments. Could some other object of massive government spending have produced the same results with regard to economic equality? I don’t see why not.

There’s no reason I can see that it would have to be spending on war–because it’s plainly the spending that’s operative here. And who spends on war? Governments. Could some other object of massive government spending have produced the same results with regard to economic equality? I don’t see why not.

@jeff I’d have to hear what other massive spending would be suggested until I could comment on it’s efficiency towards equalizing… but beyond massive spending, I have to disagree with you and suggest that the absolute wars mentioned in the article equalize economies in untold and not fully measured (data) ways. Simply (and sadly without data backup), when you have war at the scale of the two World Wars, you level the playing field, both figuratively and literally. Entire economies, cities, regions, etc. get reset to 0. Buildings get demolished, families get destroyed, long standing businesses are wiped from this earth. One has to admit, a big part of why America came out ahead after WWII, was that unlike Europe, Japan, Russia, we came out relatively unscathed and with a new modernized mass manufacturing industry ready for the next decades.

Now, I would love to see a different type of equalizer that balances things without bringing them as close to zero as possible… I just haven’t heard of one in my historical perusing yet.

@jeff I’d have to hear what other massive spending would be suggested until I could comment on it’s efficiency towards equalizing… but beyond massive spending, I have to disagree with you and suggest that the absolute wars mentioned in the article equalize economies in untold and not fully measured (data) ways. Simply (and sadly without data backup), when you have war at the scale of the two World Wars, you level the playing field, both figuratively and literally. Entire economies, cities, regions, etc. get reset to 0. Buildings get demolished, families get destroyed, long standing businesses are wiped from this earth. One has to admit, a big part of why America came out ahead after WWII, was that unlike Europe, Japan, Russia, we came out relatively unscathed and with a new modernized mass manufacturing industry ready for the next decades.

Now, I would love to see a different type of equalizer that balances things without bringing them as close to zero as possible… I just haven’t heard of one in my historical perusing yet.