Think of this as Volume 18, Number 35 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

We are accustomed to thinking of wars as being fought with guns. That’s how all 20th century wars were fought.

We are accustomed to thinking of wars as being fought with guns. That’s how all 20th century wars were fought.

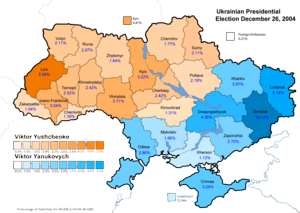

But the Ukraine and Syria show us something different. The wars of the 21st century are economic.

Right now, the European Community and Russia are in a competition to see whose economy can sink less, and which side can suffer the economic fall more. That will define what happens to the Ukraine.

What soldiers do, on either side, matters less than the willingness of politicians to support them, and that depends on popular willingness to suffer some economic loss. Vladimir Putin is betting that Russians will suffer a 10% hit to their income better than western Europeans will take a 2% hit.

Europe, meanwhile, is arguing over how to take that hit. Will the European Central Bank resort to extraordinary measures to avoid the hit, risking bank balance sheets, or will it let recession return? Already, there are indications that some Dutch banks are squirreling away cash to evade the bank’s current moves, which include negative interest on deposits. If it becomes every bank for itself, that’s a win for Putin.

On the other side, Russia’s oligarchs are taking a big hit to their wealth stoically, so far. If the West wants to increase that pressure they might tell billionaires like Alisher Usmanov, who co-owns Arsenal, and Mikhail Prokhorov, who owns the Brooklyn Nets, that they must choose between their western assets and their eastern loyalty. If they choose the western assets, Putin loses.

What is happening today in Ukraine is a kinder, gentler version of what happened 150 years ago. Putin is betting that his people will take more pain than the people of Europe will. But will they take 10 times more? If Europeans suffer a slight recession, they will scream at their political leaders, but Russia will go into depression. Is Putin ready for food lines? Russians claim they are, but after 25 years of full supermarkets, are they really?

That’s one way an economic war works. If you don’t care about your living standards, of course, ISIS (or ISIL, as the Obama Administration calls it) offers another model. The Syrian-Iraqi “caliphate” may have gotten its start-up capital from elsewhere, but its working capital today comes from oil assets it has seized and human beings it has held for ransom. These buy the guns that keep the war going.

Everything evolves. Technology evolves, economics evolves and war evolves. The willingness of people to suffer privation has always backed what happens on battlefields.

In a 21st century war it is the battlefield.