Think of this as Volume 18, Number 39 of the newsletter I have written weekly since March, 1997. Enjoy.

It’s not “the big one.” But it is a foretaste of what is to come, at some point in the next six years, as we harness more of the wind that blows, the Sun that shines, the energy from our molten rock and the cheapest form of renewable energy there is, efficiency.

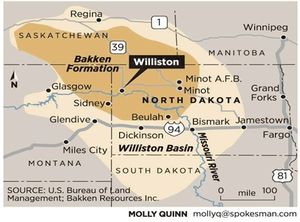

We know this is not “the big one” because this premature oil shock is the product of our own oil and gas industry. The U.S. refines about 9 million barrels per day and has three new oil production basins, which barely existed five years ago, each producing 1 million or more per day of those needed barrels.

You might even call this the Sarah Palin Oil Shock. It's not a compliment to the half-term Alaska governor. This shock is the product of a “drill baby drill” mentality from relatively small producers that has overrun the industry's willingness to invest in the infrastructure that brings it to market.

Politicians who love the oil business blame environmentalists for the delay in pipeline construction, pointing to the Keystone XL line that would run from Canada to Texas. But Keystone is actually irrelevant to the discussion. It was never designed for the Bakken. It was designed for Canada, where “tar sands” (now called “oil sands” by the industry) are strip-mined, ground, and mixed with natural gas liquids to create a bitumen slurry that can be refined after a fashion. This product carries its own discount: it’s not really oil. The economics are different. You know the stuff is there, you know how much it costs to create. The only question is whether you’ll be able to produce it profitably.

The problem in North Dakota is illustrated by the problems of a company called WTI, a unit of MDU Resources. They wanted to cut a natural gas pipeline across the state to reduce flaring, in which gas is literally burned-off at the wellhead (as bad as carbon dioxide is, methane is 50 times worse as a greenhouse gas). They announced an “open season” early this year, asking that producers commit supply to cover the pipeline’s useful life. The open season was due to end in May. As of this writing the pipeline was still not being built.

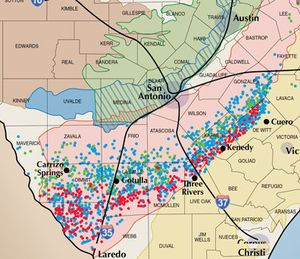

The same infrastructure weakness is now striking an even richer oil play, in West Texas’ Permian Basin. There just aren’t enough pipelines to get the oil out to refineries, according to the Energy Information Administration. This has created a “spread” between WTI and Permian prices, created in Midland, of up to $12.50/barrel, when the additional costs of transport are factored in

Partly as a result, a small oil producer in the Permian called Athlon agreed last week to be taken out by a Canadian gas company, Encana, for less than the target price oil analysts had placed on it just two weeks before. Encana, meanwhile, was buying in order to rush as quickly as it could away from natural gas, which has been in glut since 2011 – it had previously spun-out, then sold, a bunch of Canadian gas leases in order to get the cash for its oil play.

Remember what I said about natural gas? At $4/mcf, U.S. production is presently at one-third the world price. Kinder Morgan is exporting some of it to Mexico, helping take coal completely out of the energy equation there, and Cheniere says its LNG export plant will go online in 2016. But the recipients of all that gas are now having second thoughts. They’re not certain they can get the $15/mcf they’ll need to take LNG profitably.

The short term result of all this is great for America. It means that oil prices remain near the low end of the range they’ve been in since the recovery got going in 2010, which is $90-100/barrel. This is the case despite the wars roiling the international oil patch.

Russia, the world’s largest producer, continues its cold war with Ukraine. Saudi Arabia, the second largest, is engaged in the struggle against ISIS. Libya, once among the largest, is off the map entirely, and Nigeria, another large producer, could be taken out by the Ebola virus. Venezuela, once South America’s production giant, is in economic freefall and can’t raise production because its government won’t do business with the U.S., which has the oilfield technology it needs. Mexico has come to the table on that, but it’s not like you can turn production around on a dime – it takes years.

Meanwhile, renewable supplies keep rising. Demand for oil and electricity leveled off five years ago. Thanks to efficiency, they’re not rising. Solar and wind power are great at any price in the Third World, which oil bulls were depending on to take up the demand slack.

At this point, every windmill that goes up, every solar panel on every roof, is taking a small bite out of base demand. The economics, again, are different. The windmills built in 2012 are still producing, and the inefficient solar panels put up in 2009 should keep producing for decades. Costs on these products keeps going down every year. Efficiency on these energy sources rises every year. Smog is doing to China what all the political advocacy couldn’t do – pushing the government to demand new energy solutions.

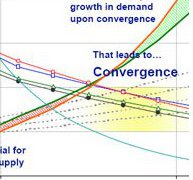

If we could force producers to pay a price for carbon, we’d be at crossover already. The fact that the oil barons have pushed back successfully, in England and America and Australia, is terribly sad. But economics doesn’t care for politics, and trends don’t take a holiday. Renewable costs are continuing to fall, oil costs are stable and rising. True crossover is just a few years away, the point where truly unsubsidized solar and wind – even when battery back-up is added – starts falling below the cost of new oil and gas production.

That’s when the real reverse oil shock happens. What we’re seeing now is a mere amuse bouche. How bad it gets for the U.S. economy depends entirely on whether young voters are so lazy, jaded, and cynical that they give the oil barons government control in November and in 2016.

But in the end it doesn’t matter. It’s just a question of time. Coal is dead, natural gas is dying, and oil itself is not feeling at all well. Energy abundance is coming. Al Gore’s kids may end up as rich as the Koch Brothers or the Cox sisters. Won’t that be funny?

Dana

It’s quite interesting, how the “green” lobby denigrates oil, quotes certain studies, uses colorful charts and speaks of the coming dire consequences of the overuse of fossil fuels, but never mentions nor refutes S. Fred Singer and Dennis T. Avery re; their well-written and well-researched book; Unstoppable (Every 1,500 Years) Global Warming.

I say facts are facts and assumptions will always be assumptions.

Stephen Hoyt

Gatineau, Qc

Canada

Dana

It’s quite interesting, how the “green” lobby denigrates oil, quotes certain studies, uses colorful charts and speaks of the coming dire consequences of the overuse of fossil fuels, but never mentions nor refutes S. Fred Singer and Dennis T. Avery re; their well-written and well-researched book; Unstoppable (Every 1,500 Years) Global Warming.

I say facts are facts and assumptions will always be assumptions.

Stephen Hoyt

Gatineau, Qc

Canada