NOTE: This article is part of the ‘Think Further’ series, sponsored by Alger Financial Management. For more ‘Think Further’ content and videos, click here.

It’s that future we’re going to create next.

Because the future we imagined in 1964 didn’t come to pass. Futurists of that year could not imagine iPhones. The communicators on “Star Trek” would be clunky by comparison.

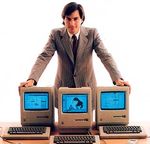

The futurists of 1964 couldn’t know about Gordon Moore and his famous Electronics article , with its drawing of “Handy Home Computers” sold alongside notions and cosmetics. That article came out a year later.

But the Internet of Things, which will bring us our self-driving cars, is being born first in industry, not the consumer marketplace. Making it happen is an integration task for experts. The IoT is already proving its value in jet engines and airliners, in factories and hospitals. It's happening without much consumer input.

The 3D printing revolution isn’t really a consumer revolution, either. HP’s recently-announced MultiJet Fusion printer is a $150,000 unit that can spray metal powders into desired forms, then fuse them.

The calling card is accuracy far beyond what is now imaginable.

The benefits of this expert-driven future are frightening to those raised

Political resistance is thus inevitable. People fear a loss of autonomy, never mind that self-driving cars could save over 30,000 lives each year, just in this country, because we assume safety in autonomy that is not there. For 50 years consumers have overridden each improvement in safety, like air bags, by driving faster, taking tighter turns, and becoming more distracted.

Arguments over global warming also sound ridiculous. It’s like arguing whether there are hats. It’s really an argument over autonomy, about our fear that we may lose control over technological change to experts.

But experts are people too. The changes we need next are too complicated for us to drive ourselves. The more promising future is all about system integration.

The SpaceX Dragon drives itself, the “uninterruptible” autopilots on Boeing aircraft stop terrorists, and features like automatic braking are emergency measures.

The world will change slowly as the system integration is completed. Drunks will only be allowed to “drive” self-driving cars. Then old people will get them, and automated taxis will take kids to school. Maybe the taxis will have little blue lights on them to warn people of the “dangerous” robots around them. Data will prove the robots to be much safer than we are, so insurance companies will make us succumb. Change will be, in part, a political process.

I’m now approaching the age he was at then. This computer I’m using is also an amazing tool, but it's one anyone can use. The file system is a mess, but the computer automatically adapts to it. I don’t expect to see the world of 2064, unless medicine advances even further than we now anticipate.

But I think the future will be electric, it will be amazing, it will be integrated, and that it will drive itself. My kids, and yours, will live longer, in greater comfort, and with greater control over the world than we can even imagine, thanks to just machines that make big decisions, programmed by fellows with compassion and vision.