(The kid on the right in this picture is me, with my dad, who passed in 1999, at the wedding of my younger sister. Just wanted to see him again.)

The online world makes liberty binary, we argued. It’s on or it’s off. Economic growth demands that it be on, so it’s going to be on. We became among the earliest cyber-libertarians.

But human nature is not binary. It’s analog. There are degrees of good and evil in all of us. And the Internet, as part of the human world, must respond to that. It’s a misunderstanding of this fact that is at the heart of cyber-libertarian dismay with (even hatred of) the Obama Administration.

The fact is that we’ve entered an era of Cyber War. The Internet has become the focus of the key struggle of our age, between modernity and medievalism. Groups like ISIS and Al Qaeda know that the best-and-fastest way to go after the U.S. and its allies is through the Internet. North Korea has demonstrated this beyond a doubt.

I want absolute privacy. So do you. I want the government to assume I’m a good guy, and I am. The American attitude is we’re all law-abiding citizens, until we crack and start shooting the government should leave me and my guns alone. That also holds when my name is Tim McVeigh or Cherif Kouachi. To take it in another direction, it holds when my name is Jimmy Savile or Ariel Castro. Or Bill Cosby? Where and how do we draw the line – at what stage of intent, and of criminality, do we tear away the veil of data that protects what we regard as “privacy” and leave our actions open to police interpretation?

What if you’re going to attack the electronics of planes in flight, or take down the electrical grid, or destroy the banking system? The Internet, in theory, now makes all these kinds of crimes possible. It’s not just finding out the name Ben Affleck uses to check into hotels that is at stake here. Planes have WiFi, grids are monitored through online assets, and banks are nothing but transaction processing machines. Governments must, to protect their citizens, have the ability to prevent disasters. That means they must be able to tell the difference between you and the monsters who might kill your family.

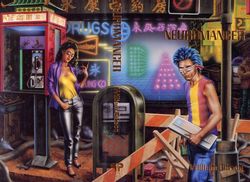

The tools with which we seek to access, and manipulate, this data are also changing. We’re moving away from the era of keyboards (unfortunately), even beyond video. Visualizing, manipulating, and moving within the haystack will take far more sophisticated tools, tools on the order of the Oculus Rift.

This is why the headline says we’re entering a Gibson age, as in William Gibson. Today, Gibson’s early books, like Neuromancer and Count Zero, read as nostalgia far more than science fiction. The cyberspace world described in them has nothing to do with what we see each day. Where is the Web? Where is the Google? Gibson became so impatient with that dichotomy that he switched from futurism to stories set in the current day, like Pattern Recognition. Even books set in the past, like The Difference Engine.

But this is the world we’re moving toward. The Administration supports the stand-by authority to access data, and to act when the evidence seems clear, knowing that clear is a relative thing. Cyber-libertarians call this a deliberate violation of the Constitution, some even call it an impeachable offense. But it’s an offense that any President would commit, based on their oath of office, and I see nothing in the record of actions by this Administration to show any motive beyond that. I can’t say that of the last Administration, and may not be able to say that of the next one.

But power is binary, too. Someone will always have it. Maintaining visibility into how they use it, and the power to change who has it, is where the rubber meets the road. Democracy is the guarantor of liberty, not laws, and not men. And it’s analog, not digital.