A lot of people like to say these days that America is no longer a democracy. True, absent a crisis, and it has always been true. Most of the time, most people don’t care. Democracy, for most of us, is a gun we keep locked in the drawer.

A lot of people like to say these days that America is no longer a democracy. True, absent a crisis, and it has always been true. Most of the time, most people don’t care. Democracy, for most of us, is a gun we keep locked in the drawer.

And that is actually fine. If you’re not motivated to vote, you’re voting for the ways things are, you’re voting “yes” on whatever those who do vote wind up voting for. If you don’t vote, then bitch-and-moan that “we’re not a democracy” and “my vote doesn’t count,” you’re an idiot. Because it’s the opportunity to vote that matters.

But there is an area where in the last several decades we have lost democracy, and seem to have lost any hope of getting it back. That’s in corporations.

Until 1985, all corporations listed on the New York Stock Exchange had to give one vote on corporate decisions to each share of stock. If I owned 100 shares I got 100 votes. Not much when there are 1 billion shares, but it offered investors a way to put a brake on the stupidity or greed of a company’s founders.

Until 1985, all corporations listed on the New York Stock Exchange had to give one vote on corporate decisions to each share of stock. If I owned 100 shares I got 100 votes. Not much when there are 1 billion shares, but it offered investors a way to put a brake on the stupidity or greed of a company’s founders.

This has largely disappeared in our time, especially among tech companies, which for the next generation will hold the kind of power over our politics and society that oil companies did in the last generation.

What started as a way to protect family-run companies from the greed of Wall Street’s Gordon Geckos has become, over the last decade, a form of corporate feudalism. The looting of companies like Adelphia in the last decade was ignored.

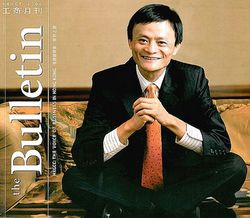

Instead, dual share structures have become the norm, especially in the tech world, where CEOs like to have fat cash piles and don’t want to fend off nasty shareholders who might want a taste. Facebook has a dual-share structure. So does Google. No one can do a damned thing about Rupert Murdoch because News.Corp had a dual-share structure, and he controlled the shares that counted. We know how this story ends because The New York Times has had a dual share structure for ages. The whole company can crash and burn, all the employees can lose their jobs and pensions, but no one can do anything about it.

When the head of a company is a unique entrepreneur, someone whose vision needs to be heeded in order for the company to succeed, there is some merit in this. But what happens when the founder dies, or retires, or simply loses the plot? What will Fox look like when the Murdoch kids get to do what they want with it? What will Google look like?

The whole purpose of democracy is to put a brake on ambition, and to put a time limit on power. That is what makes America great. We don’t tolerate Kings. We certainly don’t tolerate Dynasties.

But in the corporate world, for some reason, we do.

Public companies should be controlled by the public. If you want to control your own company, keep it private, or just don’t sell a majority of the stock. Dual share structures let people violate this principle. Worse, it lets them do this in perpetuity.

We know from history that this doesn’t work. Absolute power corrupts absolutely, and dynastic power can do this over many generations. Why should Google be run like North Korea? Because, in time, it will turn into North Korea, that’s why.

What’s worse is that the dual share structure doesn’t just hurt democracy, it doesn’t just hurt society, it hurts the companies with the dual share structures themselves. Activist investors can’t change the management at Zynga, or at Groupon, or at Yelp, or at LinkedIn. The founders have written themselves, and their heirs, into complete, eternal control of those companies. They can loot them at will, and a shareholder’s only recourse is to simply not own the stock.

If companies refuse to act, and if exchanges need to act, and if regulators refuse to act against dual share structures, then the only route open to shareholders who want a break is democracy itself. Those who argue that corporate control of our democracy is eternal, that resistance to it is futile, need to be proven wrong.

History says they eventually are. Slavery was abolished despite the best efforts of the Framers. But it shouldn’t require a Civil War to unshackle the shareholders. Corporate democracy may become the great issue of my children’s time.