I have now lived more than half my life in Atlanta. I was born in New York, but I am an Atlantan. My wife was born in Texas, but she is an Atlantan. My kids are native Atlantans.

I have now lived more than half my life in Atlanta. I was born in New York, but I am an Atlantan. My wife was born in Texas, but she is an Atlantan. My kids are native Atlantans.

Atlanta is both the most wonderful and exasperating city in America.

It is a town that claims to celebrate its history. But in fact it mostly Disney-fies its history. It fits everything into a false narrative, that of a great, humane urban place rising from the ashes of war, a progressive place, an up-and-coming and growing place.

Anything that seems to question this history gets forgotten. The outright racism of Henry Grady’s “New South” speech of 1881, summed up as “we still hate blacks but we’re ready to do business.”

The 1895 Cotton States Exposition and the re-segregation of the city that followed.

The 1906 race riot, perpetrated entirely by whites spurred on by lying editors competing for the governorship on the issue of who would move against black voting rights faster? Forgotten.

We love Alfred Uhry for his “Driving Miss Daisy,” a fantasy about overcoming racism, but his “Parade,” about the 1912 Leo Frank case (and lynching)? Down the memory hole.

The 1915 Atlanta bag mill strike, which broke the back of unionization in the south for generations? What strike? Give us “Gone With the Wind” instead, the David O. Selznick film which, while not “Birth of a Nation” didn’t have the courage to celebrate future Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel at its premiere?

And about that racial harmony. It was “sold,” starting in the early 1950s, through informal agreements between Mayor William Hartsfield and a coalition of preachers, led by C.T. Vivian and Martin Luther King. Sr. (his original name was Michael), aimed at selling the city to northern conglomerates as the “City Too Busy to Hate.” But racism didn’t die. The neighborhood I live in, Kirkwood, wasn’t so much “integrated” as taken over, the whites nearly all fleeing and the incoming blacks being ghettoized.

The key to what I call the Obama Thesis of Consensus, of course, is forgiveness, not blind forgiveness of the type we practice in Atlanta but eyes-open forgiveness, acknowledging the sins of the past and striving always to form a “more perfect” union. This is not the way Atlanta views history:

What greater form of patriotism is there than the belief that America is not yet finished, that we are strong enough to be self-critical, that each successive generation can look upon our imperfections and decide that it is in our power to remake this nation to more closely align with our highest ideals?

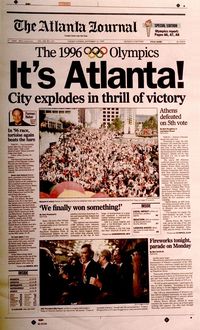

For Atlanta, it’s more important to say that we’re now 20 years removed from the 1996 Olympics, which began the “inward explosion” of the city I expected to see when I first moved here in 1983. (Oh, and was there a bombing then? We hadn't heard.)

Value today doesn’t come from offices, which are little more than glorified factories for software coders. It comes from research, from in-town institutions like Georgia Tech, Georgia State and Emory, from the interactions between those who practice discovery and those who fund and profit from it. The hottest real estate in today’s city are West Midtown, near Georgia Tech, the Old Fourth Ward next to Georgia State, and my own neighborhood of Kirkwood, two miles south of Emory. The rest of the region is still stuck in 2009, and will remain there until the abundance of renewable energy and the ease of self-driving cars makes distance attractive again.

Atlanta today is having a moment. We have the chance, right now, by expanding these zones of prosperity, to make Atlanta majority upper-middle class, rather than the majority-poor city it has been since “integration.” This would transform the politics of the region. Spreading the poor out among more jurisdictions would make the move of the Braves to Cobb County be seen for what it actually was, a last-gasp fleecing of crackers by a multi-billionaire in Colorado named John Malone, a last effort by a white power structure to turn Atlanta into Detroit, and burn every black man and woman (and liberal) to a cinder inside its crime-ridden precincts, as was done there.

That kind of crap has to be stamped out. The reality of the region has to start matching its rhetoric. If it does, Atlanta has a grand and glorious future ahead of it. I wonder how much of that I might live to see?