In the last generation it was oil. Before that, manufacturing. Before that, utilities. Before that, banking. Ever since we ceased to be an agrarian nation, with the outbreak of the Civil War, American politics have been driven by the scene of a rising industry, a ruling industry, and a falling one.

Consider my own time, the era of the Nixon Thesis, 1969-2009. The manufacturing industry was falling, as Detroit was hollowed out. The oil industry was ruling, as Houston and Dallas gave us Presidents and wars over resources. The technology industry was rising, with kids my own age named Gates and Jobs becoming multi-billionaires, and with the Web being spun.

After leaving ZDNet in 2010, my first task was to cover renewable energy, which is the application of technology to power. Oil is based on the idea that you find stuff you can burn, deep underground, you bring it to the surface and you burn it to create power.

Solar and wind have a different set of economics. You create a machine to harvest energy that already exists, all around us. That device remains in place, harvesting energy, for years, decades even. The capital cost of the machine is recovered over time, and the energy produced after it’s paid for is, in essence, free.

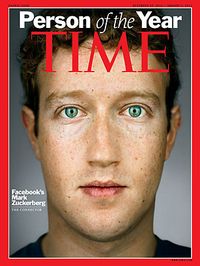

I call this piece the Facebook primary mainly because its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, is now just 30. Even if he wanted to become President next year, he’s too young. But he doesn’t want to be. What he wants to be, what he’s going to become, is the most powerful political arbiter of his time.

That’s because Facebook has gone from literally zero to $220 billion in less than a decade, using the resources built by Google and others to deliver enormous value to buyers and sellers in the new digital marketplace. Facebook, and companies like it, are the future. Facebook is now worth more than Chevron, more than BP, more than General Motors and Ford combined.

By the time the 2016 election rolls around, Mark Zuckerberg will be worth as much as a Koch brother. Larry Page will be worth as much as a Koch Brother. Bill Gates is already worth more than both Koch brothers. Behind them are literally dozens of others, millionaires and billionaires, strivers and entrepreneurs. Elon Musk is worth $12 billion. There are lots more where they come from.

What does Mark Zuckerberg want from politicians? He wants policies that favor the “knowledge economy,” that create win-win relationships. He wants, in other words, consensus, which is at the heart of the Obama Thesis. What does Larry Page want? Mainly, political balance. We know what Bill Gates wants, a more caring world. In general, Silicon Valley is filled with cyber-libertarians, people focused on growth and change, on the application of science and knowledge.

What does that mean for our politics? Right now, it means general approval for the policies of Barack Obama, with some exceptions. The cyber-libertarians don’t like the NSA, they don’t like the idea of “regulating the Internet,” they accept climate science, they vaccinate their kids but don’t want to be told they have to. Because, freedom.

But I don’t think it will be, because of self-interest. As Zuckerberg notes, the Valley is based on creating win-win relationships. It’s not about access to resources, which is what it was about during the Nixon years. It’s more about free trade in ideas and virtual goods. In that way it’s similar to the ethos of the FDR Era, what I have in the past called the “Thesis of Unity.” or even the earlier Progressive Era, where utilities accepted regulation so that manufacturers could be assured of a steady price on the inputs they needed to grow.

The change represented by the 2007 Google meeting is a permanent change. Don’t let any headlines dissuade you from understanding this reality. Power has shifted, from Texas to California, and it’s not moving back in your lifetime.