It’s moved.

Seth Stevens-Davidovitz, a Google scientist who moved to The New York Times to do “data journalism,” did the research but, because of how he wrote his story , it was not really appreciated.

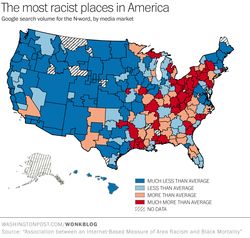

His method was to use Google Insights and search for racially-charged terms, like the one the President offered Marc Maron last week. He used data from 2004 to 2007, before the President won election, in order to take him out of the equation. Then he looked at where the queries came from, comparing their frequency across metropolitan areas.

Instead, there is now a “Cracker Belt” in America. It runs up the Appalachians, through Ohio and Pennsylvania, and into western New York. Southern New Jersey and Ohio are now, on balance, more racially charged than Georgia. Yet these are areas with relatively low black populations. West Virginia, which is at the center of the “Cracker Belt,” is only 3.2% black. One of the most racist areas in America is the Upper Peninsula of Michigan extending toward Duluth, Minnesota, which is just 2.3% black.

What’s going on?

But outright racism, in our time, is now centered in places where racial diversity barely exists. Which means it’s coming from some other source. It’s coming from the political climate, and it’s coming from the media. Which means, to me, that its origins are economic.

This is actually good news. It means that racism today is far less intractable than it seems, because it is less rational. In fact, racism today is mixed-up in a host of white “identity” issues – guns, abortion, gay marriage – based on economic issues, like the fall of coal and of manufacturing. (Note that Duluth is at the center of the old “iron range,” a center of mining.) Racism, in other words, is now a byproduct of financial and spiritual poverty, of insecurity that the media and politicians are quick to take advantage of, driven as they are by wealthy owners seeking distraction.

Most Cracker Belt economies are now built on tourism. That’s a low-wage service economy. The most racist part of New England is Rhode Island, whose economy now is mainly based on people from elsewhere in the region coming in for fishing, sailing and swimming. Just about all Cracker Belt economies are economically depressed. The good jobs have gone away, and what remains are service jobs. The fact that the services are serving white folks doesn’t mean the resentment against it isn’t real. Dad may have been an engineer or a factory worker, you’re slinging hash or flipping burgers, and you’re mad as hell about it.

In other words, racism today is being engineered. And if racism is being engineered, it can be reverse-engineered. This is what makes the Bernie Sanders campaign important.

There is no longer much doubt that Hillary Clinton took advantage of engineered racism in her 2008 campaign. She beat the President soundly across the Cracker Belt, in places like West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky. A lot of folks figure this makes those places naturally conservative, but what they are is disadvantaged, and an economic campaign, from a white candidate, focused on that disadvantage could catch fire.

A campaign of economic discontent, aimed mainly at white voters, could do more to shake up the status quo in places like West Virginia and Ohio than anything else that might happen, in what looks right now like a boring election year. It might even cause the blinders of racism to fall from some eyes, and cause low-wage workers to see wealth as the enemy rather than race.

What might happen then?