We root for criminals. We always have.

When baseball players take steroids, baseball writers don’t root for those players. When politicians lie, or steal, political writers will turn on them in a minute. Even an entertainment reporter will destroy Lindsay Lohan in a heartbeat.

But the financial press isn’t like that. For some reason, we identify with the criminal classes. When the cops come we stand on the street and demand they not arrest anyone. When the lawyers come to sue, or when the politicians come to pass laws aimed at halting the crime sprees, we act like it’s the criminals who are being put upon.

This has been the case ever since I started in this business, and there is a reason for it.

Business won’t stand for honest advocacy. A reporter who is an honest advocate for the proper role of business, for law and order, is not going to be in the financial reporting business for long. They demand sycophancy, even when it’s not in their best interest, even when it means having their own reputations ruined by someone else’s greed.

That is the way it is, I was told, 35 years ago now. And that is the way it still is.

That’s the way it was during the 2008 financial crisis. Business reporters didn’t call for the heads of the banksters. They still won’t. They are still appalled that the Justice Department says that, in the future, it will go after individuals for actions they do in the name of their corporations. It’s as if the handcuffs were coming down on our own wrists.

Finally, after Hillary Clinton saw a story about it in The New York Times and tweeted that she would do something about it, the financial media struck. Guess whose side they took – not just Fox Business but CNBC as well? Why Shkreli’s of course. He was breaking no law, and Clinton’s threat to change the law caused the prices of other biotech companies to fall almost 5% in one day – so it was all her fault.

Really? Really. If you were in a crowd and a pickpocket were in your midst, would you attack the police who came in to arrest him? Would you scream “police brutality?” Of course not. So long as the pickpocket wasn’t killed, so long as the police followed proper procedure, you’d be on their side.

But that doesn’t hold in the financial press.

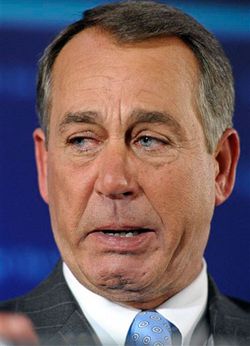

It is this attitude that gives businesspeople the idea that they can do anything, that they can act with impunity and that laws or norms don’t apply to them. Did the CEO of Bank of America say he wouldn’t take the chairman title, then turn around and take it? Guess whose side Jim Cramer took on that one? Roll 212.

To a great degree, then, I place the blame for what Volkswagen did squarely on the financial press. We let these bastards get away with it, time after time after time. So they did.

The first lecture I ever got in journalism school, over 38 years ago now, still stays with me. The late George Heitz, then with the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern, gave it. And the very first thing he did was yell at us. We had all come into the lecture hall, a theater-like room, and sat in it like students.

“You’re not an audience,” he thundered. “You’re witnesses. You run to the front, and you have your questions ready. You are not here to be entertained. You are here to witness!”

About six months later the department head, the late Elizabeth Yamashita, gave all of us in the Business Reporting class great news. “You’re all going to get jobs,” she said happily. And she was right.

She should have given us some George Heitz at the same time.

good one

good one