(What follows is a work of fiction. I wrote it early this year, in about a week, after a weekend vacation to Asheville, touring artists' markets. Hope you like it.)

____

A cup or goblet, made of clay, and fired with a simple limestone-colored glaze. I saw it in a storeroom, by the workshop of an artist who was now working, instead, on cartoonish wiener dogs hipsters could hang on a wall.

The price was a snip, $19. I asked what inspired her to make it. She didn’t answer. All she said was, “It’s on sale,” as she wrapped it in newspaper.

I thought no more about it. I was giving my wife our hundredth honeymoon, a weekend in the North Carolina Mountains. There were other artists to visit, and the Google Map on my phone was buzzing in its cradle. We had to move on.

I was on my second or third cup of coffee, sitting at my desk and wondering what I might write about, when the doorbell rang. It was the Witnesses, again. Our neighborhood is loaded with Witnesses, mostly lovely older black people who wander the street in conservative suits and dresses, even on the hottest summer days. I’ve become friendlier with these folks as the years have passed. Not that I’m religious, I’m not. But I have come to find their belief in belief comforting, and I’ve also grown closer to them in age.

On the porch stood a woman of about 50 in a white dress that offset a pattern of what could have been blood or jelly spatters. She was fanning herself without shame when I answered. Usually witnesses walk to my door slowly, knowing that most doors get slammed in their faces, prepared for it and holding on to one another for support with invisible chords of faith.

But this woman was having none of that. “Where is it?” she asked breathlessly.

“Where is what?”

“The grail. Where is the grail?” She was breathless, anxious. I motioned her into my air conditioning and, to my surprise, she took me up on my offer, looking around her feverishly.

“How did you find out about it?” I asked with surpassing calm as I walked toward the cupboard and pulled the small yellowish goblet from its place.

Rather than answer my question, the woman fell straight to her knees in my living room. I rushed over, fearing she’d had an attack of some kind. “Is it?” is all she said. Then, a few breathless moments later, “Is it real?”

“May I hold it?” she asked plaintively.

“Why certainly,” I said. “But you may want to stand up, for balance. You wouldn’t want to drop it.” I was still joking, she wasn’t. She jumped up like an athlete and I handed the grail to her.

“It’s a simple thing, really,” I said as she cradled it like a baby. “I thought I might write about it,” I added, motioning around the office, where my PC was already on, and again holding the coffee mug as a badge of office.

“My Lord,” the woman said, slowly. Then she took another breath. “My sweet Lord.” She held up the grail to the light of the morning sun. Then she turned it, looking up the stem, where the price tag had been the day before. She smiled, tears came to her eyes, and I smiled toward her because it was all I could think of to do.

“Look,” she said, holding the grail out to me. I took it from her trembling hands and looked as she had, from the bottom, past where the price tag had been, toward the center of the cup. I couldn’t see all the way up the stem. It looked black in there.

“Like there’s a hole,” I said. “I hadn’t noticed the stem was hollow before.” When I turned the goblet over, I could clearly see that the cup was finished, complete. Besides, if there had been a real hole I would have seen light coming out the other side.

“The Holy Grail,” the woman said, this time through tears. “I have touched it. I have held it. Hallelujah, praise Jesus.” And there she was on her knees again.

“It’s just a cup, a goblet” I said, no longer laughing but truly alarmed. “I found it at an artist’s shop. Yes, a goblet can be called a grail. It is grail-shaped. But…”

I couldn’t get out another word. “And Peter denied him, three times,” she said.

“The name is Dana.”

“Three times,” she said, holding three fingers in front of my face. “You shall deny me three times.” Her head moved up and down, slowly, her eyes bore into me, then she turned around with a flounce of her long skirt and walked out.

“OK, then” I thought as I sipped my coffee. I put the grail, goblet, cup back in its cabinet and went back to work.

–

The next day dawned sunny and bright. The wife had gone to work early again, and so had the kids. I slept in until almost 8, then decided to take my coffee to the front porch before dressing for another day of writing.

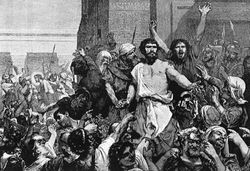

My eyes were looking at the patterns on our wood floor as I opened the door. I was blowing on the coffee, wearing my summer weight robe, which might look attractive were I an attractive man, and not a late middle-age mess. I heard a roar like the rush of wind in front of me, and looked up to see a huge throng of people all over my lawn. They filled the street, and the neighbors’ lawns too. They looked at me, and I looked at them, blinking.

“Grail Man. Grail Man. GRAIL MAN!” They thundered it, like I was an Atlanta Brave who had just homered to win a play-off game.

“Howdy,” is all I knew to say, and I waved. I pointed to my cup. “Coffee,” I said. “I haven’t had my coffee yet.”

“Let us see the Grail” said the woman in the front. Christ, I thought, you’re young enough to be my granddaughter. “You have the Grail. Let us see it!”

“Can I get a sip of coffee first?” I asked her, ignoring the others because they were too much to take in first thing in the morning. “Can I at least put on some pants?” I added.

“Show us the Grail! SHOW US THE GRAIL!” shouted the crowd in response.

I held my right hand, the one that had been waving, down, a signal they should quiet a little. The neighbors would be heading to work in a little while, and I had no idea how they would get their cars out of their driveways. This was ridiculous.

“Can you come in and get it?” I asked the woman in front. She appeared to be about 20, and her hair reached below her shoulders. Above the skirt she was wearing a John 3:16 t-shirt, the kind I really don’t like, which stretched over ample breasts.

The young woman nodded, solemnly, and followed me inside. I set the coffee on the dining room table, opened the cupboard, and extracted the cup, the goblet, the grail if you will. I turned back to the woman.

“Here it is. Could you bring this out to show people?” I asked. “Carefully, please,” I added, as though this really were what thought it was, a religious relic, not some $19 goblet I’d picked up from an artist’s shop a few days before.

She nodded, again, even more solemnly than before, as I placed the goblet in both her hands. “I’m going to get some pants on if you don’t mind,” I said, and went off to my bedroom.

When I returned, a minute or so later, wearing jeans, a button-down shirt, and my hair patted down, she was still there. She hadn’t moved. Her eyes darted this way and that, to my fireplace, to my office desk, to the cupboard from which I’d extracted the goblet (or grail or cup). It was as though she were trying to memorize the space, the TV, the piano, the fireplace with its old encyclopedia on the mantle, even the “Pete the Cat” print with Einstein turning E=MC2 into mouse, a miracle of artistic math.

“Shall we?” I asked, and she startled as if from a trance. “Would you like me to hold it?” I then asked, motioning toward the grail in her hand, and she immediately handed it back to me, the way soldiers hand over a folded flag at a funeral, as though she didn’t trust herself with its power.

We walked out together and I took the stem of the goblet in my fist, holding it up to the crowd. Immediately a great cheer rose up, and the woman, now beside me, clapped and screamed so loudly I thought about dropping the thing.

“The GRAIL! THE GRAIL! THE GRAIL!” shouted the crowd. It was like a soccer crowd, I thought. Or what a politician hears during the late stages of a Presidential campaign, whether or not they’re winning. It was eerily appealing, and powerful, I thought. I felt the crowd’s energy like a physical force holding me up.

I looked behind me, saw a plastic lawn chair we always left on the porch for when the wife joins me for a drink on a summer evening, and pulled it behind me so I be more comfortable. “How can I convince you this is nothing special,” I muttered to myself.

Then, sitting down, I said loudly, “Would y’all like to touch it?”

The cheering stopped, and the crowd started forming a surprisingly-orderly line, next to the young woman I had brought inside, who now seemed to have some unofficial position of honor among the group. I held the goblet in front of me, the base resting on a knee, one side gripping the stem, as each person came up and, reverently, felt the top of the object, usually running a few fingers along the rim of the cup (or goblet, or grail, whatever). Their reactions differed. Some looked at me as though angry that this miracle had come to me and not to them. Others were in a state I can only describe as religious ecstasy. It turned out there were several mothers there with young children, and I held the goblet a little more tightly as the kids touched it, lest they break it.

This went on for a couple of hours, as the sun rose over the trees and blinded me, each person in the crowd taking just a few seconds with the thing, then falling back and contemplating it. Many prayed, heads bowed. Some lifted their hands up after touching it, as though asking for guidance. Still others just kept silly smiles on their faces. I took in each face in turn. Most were white but there were also many black faces. There were also some Hispanics although I wasn’t aware of any living nearby.

The last few were just finishing with the goblet, or grail, or cup, or relic, whatever it was, and I was starting to relax, when the sound of sirens came from up the street, by the train station, and several police cars pushed through the crowd, which parted reluctantly before them.

Policemen poured out as though they were in clown cars, and began creating a perimeter in my lawn. One knocked his head against my bird feeder, and started swinging his nightstick, looking for his attacker, while the people around him laughed. The laughter was good-natured, and diffused the situation. As he calmed the officer felt hands touching his arms and back in a friendly, good-humored way. After a few moments, he looked up at the bird feeder, which was still swinging from its branch, and smiled in understanding.

“Mr. Blankenhorn,” said the lead officer.

“Yes, sir,” I said. “Would you like to touch the Grail?” I think I’d gotten rather into the spirit of the thing.

“No.” Something about the way he said it sobered me up fast, and I felt in the presence of police again.

“OK.” So I stood and placed the grail, souvenir, goblet or cup or relic on the pedestal of the porch, next to a basil plant. I felt hundreds of eyes turn from me to the pedestal.

“Did you start this demonstration?” the officer asked me.

“No, sir,” I said. “And I don’t know that you’d call it a demonstration. None of these people have made any demands. Although come to think of it we really need some crosswalks down at the end of the street,” I added, pointing that way. “All these people were here in my yard when I woke up. Are you going to arrest me?” The last was said more loudly, spoken as a challenge, not my kind of statement at all, but the crowd was with me and I had gotten carried away again, feeling their power.

“Are you in danger?” asked the cop.

“Do I appear to be in danger?” I asked, “although the question should also be are you in danger, and the answer to that would be no.”

“Would you like our help?”

“Do I look like I need your help?”

“What is going to happen to these people?” the cop asked, now completely at sea as to how to proceed.

“Why don’t you ask them?” I said. Then, in a louder voice, I spoke to the crowd. “This Atlanta Police officer would like to ask y’all a few questions.” It was an announcement. I sat down again in my plastic chair (or throne or whatever) so the cop would be the biggest man before them.

“Uh, have y’all eaten?” asked the officer. Strange question, I thought, but come to think of it I hadn’t had any breakfast yet either, just a few sips of my coffee, and my blood sugar was starting to feel it.

There was a great shaking of heads from the crowd. They hadn’t eaten.

I came back out a few moments later having opened a pound of smoked salmon I’d bought at Costco, and carrying a sleeve of Einstein bagels in a bowl.

“Maybe this will help,” I said helpfully, with a sly smile and something like a wink to the crowd. “It’s just a pound of fish and a few loaves of bread, but maybe this will help y’all go on your way.”

The woman who’d walked in with me took the bowl with the bagels, and another woman at the bottom of my steps took the fish on its black tray. They began passing among the people as though this were a communion, one small bit by one small bit, and I turned to the police officer.

“Problem solved,” I said, then, in a quieter voice, I added “Maybe they’ll break up after this. I’m hoping they do, at any rate.”

I sat back down in my plastic chair, the officer standing beside me, and we surveyed the peaceful scene together. After a few minutes of quiet on the porch, with just the murmur of people seeking something of the bagels and fish to break the quiet, I nudged the policeman quietly in one arm. “Would you like to know what all this is about?” I asked.

To my surprise he nodded, and I stood up, picked up the goblet from the pedestal, and led him across the porch to our old swing. We stood there together as I showed it to him. “Really, it’s just an ordinary goblet I bought at an artist’s shop over the weekend, up in Asheville,” I said, in a confessional tone, “or a cup, which they call a grail, which is another word for it. A woman came by yesterday and treated it like some kind of religious relic. Then I woke this morning to all of this. And as God as my witness, officer, that’s all I know.”

“Hmmph,” said Officer Pete, turning toward me and away from the crowd.

“Hmmph indeed,” I said.

“Maybe they will break up after a little while,” he said, doubtfully.

“That’s the hope,” I said.

“Playing the loaves and fishes line may not help, though” the officer added.

I shrugged. “I didn’t know what else to do. You are the one who asked them if they’d eaten. I was raised Catholic, but that was a long, long time ago.”

“Not a church-goer?”

“Not really. We go to services most Easters,” not mentioning that the last time had been some years ago, “but no, I guess I’m just another secular humanist. You?”

The policeman looked this way and that before responding. “Sort of the same, but my wife tries to drag me to mass every Sunday anyway. With the kids.”

“I sometimes worship at St. Mattress by the Wall myself,” I said.

“My church, too,” he said, now smiling.

By this time the noise level was rising in the crowd, and the two of us turned toward it. The young woman who’d gone into the house with me still had the bowl, and the other woman still had the plastic tray. But where I had brought out a half-dozen bagels and a pound of fish, there was now an overwhelming amount of bread – rolls, doughnuts, slices – and heaps of bacon, cans of herring, even a whole smoked whitefish chub on the tray.

“What the…” was all I could say.

“It’s a miracle!” the two women cried at once, and the cheering began right behind them, growing as it reached the edges of the crowd, and rising as a crescendo before my startled gaze.

“I think I need to take you in before anything else happens,” said the police officer, suddenly. “For your own protection.” I was still holding the grail, and in something like shock, because I hadn’t even locked my door, I followed the officer as the other police lined up along my sidewalk. When we got to the lead car my head was pushed in, so as not to hit the top of the door, and we drove away.

—

They let me keep the grail as they patted me down – I didn’t even have my keys or wallet on me – and I placed it carefully on the table as one of them fingerprinted me. Then I was led to a shared cell, where I sat down, still holding the grail, and began to cry.

What in the hell was happening? “Why me, Lord?” I asked, a strange thing to say since I hadn’t addressed God personally for decades. I wondered if she’d recognize me.

I guess I cried for several minutes, seeing nothing, and holding the grail tightly in my lap. My legs were folded into an Indian seated position I hadn’t been able to really get into for years, but there was none of the pain I’d always felt before when seated that way.. Usually I get pins-and-needles in my feet, a nagging pain in one hip, a point of pain in one knee when I sit Indian-style but this time, despite being on hard cement and with nothing but an iron bar behind me, it felt like nothing.

Finally, I looked up toward my surroundings. There were other men here. Mostly black, a few Hispanic. I was the only Anglo face in this crowded holding cell, and certainly the oldest as well. I expected to be attacked at any moment, the grail ripped from my hands, my body left bleeding and broken on the cement.

But that isn’t what happened at all.

The men had already waited me out for some time. Now one of them, wearing a sleeveless vest, no shirt, and jeans held up by a rope belt, like an extra in “Porgy & Bess,” without even shoes on his feet, looked down toward me and reached a huge hand downward to lift me to my feet.

“What troubles you, brother?” the black man asked.

I choked back my sniffles, I tried to find my courage and failed. This man was a half-foot taller than me, and there were a dozen or so others around him. “I’ve never been arrested before,” I said humbly.

“You get used to it,” came a voice from the other end of the holding cell, and the rest of the men laughed.

“Why have you been arrested?” the huge black man asked, in a kindly voice that reminded me of Morgan Freeman, a voice that caused me to relax and my emotions to calm.

“I, I don’t know exactly,” I said, trying to think of something I could have done wrong. “I was in front of my own home. I don’t think I did anything.”

“Preach it!” said the voice from the corner. “Same here.” There was some chuckling, some murmuring, but the large black man before me held up a hand for silence, and surprisingly silence came.

“Was it, perhaps, disturbing the peace?” he asked, not unkindly.

I nodded. “That’s probably what they will call it,” I said, and the whole story of the morning began spilling out. As I finished I held the grail out to the huge black man, who took a step back as he took it into his giant hands, and examined it reverently.

“I have heard of such things, but never expected to see it,” he said. “There are many tales, from many branches of faith, of objects like this that heal souls for some reason. The history of the Catholic Church is filled with such stories. Bones of saints, bits of the holy cross, the shroud of Turin.”

“You sound like a scholar,” I said, “but you don’t look like one. What brings you here?”

He chuckled, and pointed to his unshod feet. “I don’t exactly know that myself,” he said. “Vagrancy, I suppose.” All the other men were wearing socks and, usually, sneakers, although there were a few leather soles about.

“So what happens now?” I asked.

The voice that had been cracking wise came through from the corner. “We wait. After some time we’ll be arraigned. We get a bus ride downtown, we go before a judge, and hope to get back in time for dinner.”

“Maybe YOU do,” said the voice. The men around him laughed, except for the huge one before him, who seemed to shiver a little.

“You haven’t been arrested before, either,” I said quietly, hoping no one else would hear.

He nodded, slowly. “Many times,” he said, holding out a hand to shake. “And, for what it is worth, my name is Barabbas.”

Now it was my turn to shiver.

—

I was still holding my cup, or goblet, or grail, or relic, but in a very shaky hand, an hour later when we were herded into a gray bus, shackled together to prevent escape. The chains would come off at our destination, each prisoner’s chains being taken off one-at-a-time, surrounded by sheriff deputies with guns drawn, to prevent escape.

This is ridiculous, I thought. I was standing on my porch a few hours ago. I did nothing but hold this stupid cup (or goblet or grail) in my hand, and play along with a bunch of very confused people. I thought seriously about dropping the grail (or goblet or cup), smashing it into pieces. A $19 bargain wasn’t worth my freedom.

Then I thought better of it. At least, I thought, wait until you know what they’re charging you with.

My fellow prisoners took it all very calmly. They joked as our bus pulled away from the jail. I was seated next to Barabbas, who still looked out of place in his rope belt, naked feet and over-stuffed shoes. I was having flashbacks to my days in Catholic school, and didn’t like my future as a Christ-figure.

Then I had a flashback to Monty Python’s “Life of Brian.” “Bring forth Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer,” I thought, but was surprised to find I’d said that out loud. The conversation on the bus stopped, and only started again when Barabbas laughed very loudly, indicating it was all right.

“Street clothes before an arraignment means you’re not yet a prisoner,” Barabbas said quietly as we were led off the bus. It reassured me, but only a little bit. We were led into a holding area and then, two by two, we were herded into another room, and prepared for our appearance at court.

There, in that small holding area, surrounded by sheriff’s deputies, I looked at Barabbas. He looked at me, and I had a rather strange thought. “What size are your feet?” I asked him.

“They’re feet, so far as I know,” said Barabbas.

“So about a Size 12?”

He shrugged.

I took my left foot over the bottoms of my right sneaker, and lifted the right foot up, removing it. Then I took the right foot, shod only in a sweat sock, and put it over the bottom of my left sneaker, removing it.

“Put these on,” I said quietly. “It might help.”

Barabbas shrugged, and placed his feet into my shoes. They fit. I don’t know how he felt about it, but I suddenly felt better.

A deputy grabbed each of us by the left arm before the door before us would open. I nodded toward mine in as friendly a manner as I could, but got no reaction.

But the courtroom I now faced looked strange. There were many, many people behind the bar, along the benches. They weren’t seated, they were standing, because there were so many of them. They spilled into the aisles, and the door to the hallway was open, it too was filled with faces.

Most of them, to my shock and surprise, were white faces. I recognized some of the people who had been on my lawn earlier in the morning. I nodded toward them, not smiling, and tried to bring a finger to my lips to quiet them, but the deputy saw something in that and shoved the hand down.

I turned toward the judge. It was a tired-looking black woman, white-haired, wearing glasses down her nose as we middle-aged do, shuffling the papers before her with head bowed, paying almost no attention to the crowd in front of her. There was a gavel-and-block to her right and, after looking up from new papers given her by a white, male bailiff to her right, she banged the gavel sharply, once. The room fell silent.

“People vs. Dana Frederick Blankenhorn,” said the judge. “The charge is simple disorderly conduct.”

“Here, your honor,” I said reflexively.

A younger black woman stepped forward from the desk on the other side of the room from me. “Mr. Blankenhorn was taken into custody this morning because a crowd had appeared on his lawn and he made no attempt to make it disperse,” the woman said, never looking up from her own set of papers.

“How do you plead?” asked the judge, trying to move things along.

“I don’t know,” I said.

The judge looked up from her papers, and removed her glasses. “Excuse me? It’s a simple question, guilty or not guilty?”

I looked up. “I did try to get those people to leave, at first,” I said. “Before the police arrived. I just walked out of my house, carrying this,” and holding up the grail in my right hand, “but they held a sort of worship service in front of it. When the police arrived, I know I wasn’t told I had to tell people to disperse. So the answer to your question is that I don’t know. How would you plead if it happened to you?”

I was earnestly looking for an answer, but the judge didn’t look at all pleased with my speech, and there was an outpouring of laughter from behind me, which I heard Barabbas joining in on.

“I’m sorry, your honor, but it’s a serious question,” I continued. “Nothing like this has ever happened to me. I’m, frankly, not a religious man. But some people seem to have mistaken this,” I held the grail up again, “for some sort of religious object.”

The judge had lost patience. “I’ll enter a plea of not guilty for the defendant,” she said. “Bail?”

The young woman stepped forward again. “This is a misdemeanor charge carrying a penalty of a year in jail or a $1,000 fine,” she said. “Given the defendant’s record, I think a bail of $1,000 should be plenty to handle the fine even in the case of flight.”

I gulped, but I had $1,000 in the bank. Somewhere. I looked behind at the crowd, hoping to find my wife there, but I couldn’t see her. I missed her at that moment, terribly.

A voice came from behind the bar. “Who pays this bail?” said the voice. “I mean, can anyone pay it? On the defendant’s behalf?”

The judge, who seemed anxious to go on to the case of Barabbas, seemed taken aback. “There’s nothing in the law that says the defendant must pay the bail, only that the bail must be paid. Moving on,” she added. “The state against Barabbas Johnson.”

“The charge is the same,” said the young woman as a murmur grew behind the bar and the judge rapped for order.

“Not guilty,” came the voice of Barabbas, to my left. “I have done nothing wrong,” he added.

“Same bail request,” said the young woman.

“Same bail. One thousand dollars,” said the judge, rapping again. “Let’s get these men out and get on with things.”

But the murmur was growing. I saw a young man remove a baseball cap, and place a ten dollar bill in it. I saw the cap begin to move in the air, around the room, passed from hand to hand, the noise growing, as more bills were placed into it, the way an offering is collected in church.

“Your honor,” I said, gaining some courage, “I cannot in good conscience leave this court free and see my friend here left in your jail. I would like to pay his bail for him, but all I have are credit cards.”

“Cash only,” said the judge, rapping her gavel again and motioning the bailiff to clear her courtroom.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Maybe what I’m saying now is indeed disorderly conduct, but I want Mr. Johnson to walk out of here as well. We’re both accused of the same thing. We both believe ourselves not guilty. Why should a middle-aged white man go free while a black man goes to jail?” I arched an eyebrow at the judge, and then at the young woman representing the county.

The two black women representing the state were plainly losing some patience, and the sound behind the bar was only growing in intensity, as the hat began to fill and people began throwing bills toward it, like it was a game, or a Frank Capra movie. A young white man sitting at the desk beside me, who hadn’t been heard before but was probably, I guessed, representing the public defender’s office, was handed the hat and began counting the bills, his eyes growing as he did so.

“Your honor,” he said, “There is a lot more than $2,000 here. Cash.”

“Bailiff, count that money and if there is $2,000 release both prisoners,” said the judge. “I have work to do, and we can’t proceed to the next case until we dispose of these.”

“My apologies, your honor,” I said from amid the hubbub, and my voice did more than the judge’s gavel had to quiet the crowd. “I want to thank these people whom I can only call my neighbors, and to thank you for your patience.”

The judge, mollified, nodded and smiled toward me. A deputy sheriff took my arm, in a more friendly way this time, and another deputy took Barabbas, in the same way, so we could be processed and released.

–

“Wait a moment,” I said, touching his shoulder. He looked up. “My socks are thick. Let me get you some new sneakers, at least. I know a guy. He’s not far away. I can pay for them after I get home, and get my wallet and car together, I know. Besides, I’d like to talk with you, if I may.”

The big man shrugged his shoulders, in a non-committal way. But when he stood up, my shoes were still on his feet.

I smiled. “I’m just trying to figure out what happened in there,” I said. “What do you do, by the way?”

Barabbas Johnson smiled, more broadly than I’d seen him smile before. “I’m a preacher,” he said calmly. “I was caught in the performance of my duties.”

I sighed. “Then you are just the man I need to talk with,” I said. I placed a hand on Barabbas Johnson’s back, and we walked toward my shoe store, ironically called One Step at a Time. We did it slowly, so he could explain these mysteries of faith to me.

By the time he had on the new shoes Barabbas was holding the relic, or grail, or goblet, or cup and I felt the weight of it leave me in the form of a cool breeze coming through the trees.