Manufacturing rose during the Progressive Era, ruled during the New Deal era, and fell during the era of Nixon. Oil rose during the New Deal era, ruled during the Nixon era, and is falling now during the Obama era.

The same pattern holds for technology. Technology rose during the Nixon era, and now is its time to rule. That is not a fate it can escape. The alternative is too dismal to contemplate, continuing political domination by industries and people antithetical to tech’s interests, like the Koch brothers, whose money comes from energy and manufacturing.

As an industry rises, what it most wants from government is to be left alone. As it rules it first wants to eliminate other interests’ interference in its progress, and then seeks to maintain that control in defiance of larger economic trends. That’s what is behind the larger political cycles of American politics, and it has been since our nation’s founding. The business of America remains business, and that is at the heart of our global leadership. Lose that and we fail. So does everyone in this country.

So 2016 is a very important year for technology’s leaders. For people like Bill Gates, Larry Page, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg, who have become wealthier than anyone can imagine during this decade, now is the time to step up.

That doesn’t mean writing a check. There are important issues that they need to become far more deeply involved in than they are. There is a political agenda to be defined and pursued.

I’m talking about more than getting kids into science or STEM courses. I’m talking about something other than putting money into a few charter schools. I’m talking about basic education concerning technology, about what its progress means, about why that’s important, and about what it can mean to people. Think of it as 21st century civics.

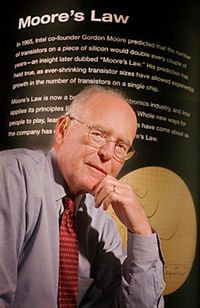

How many Americans even know who Gordon Moore IS? How about Tom Watson, Senior or Junior? (Not the golfer.) If you don’t work at Intel or IBM, the chances of this are minimal. We know Steve Jobs, but mainly as a character in a movie, through his appearances on-stage showing off gadgets. What’s behind the legend, the importance and reach of the “user experience” idea – most can’t conceive it.

Technology – its history, its importance, the way it works and changes and destroys as well as creates new work – this needs to become a vital part of the curriculum. Without it, there is nothing on which to base political allegiances that are supportive of technology.

Critics on the left and right will call this “indoctrinating” kids, but there are serious misconceptions out there that need to be dealt with, or technological progress becomes politically untenable. For one thing, there’s this idea that having your kids do the things you did is an ideal, or even something to be wished for. The parents who wanted their kids to go down into the coal mine, those who wanted their kids to go to work in the auto plant, and those who today think that being a middleman in insurance, cars, housing, or banking, as they were, is the way to a secure and happy life were, and are, wrong.

Mine has been. The great 19th century authors had to work in media other than books. Dickens wrote his stories in newspapers, and Arthur Conan Doyle in magazines, because it was the only way to get paid. Throughout the 20th century the media industries existed as gatekeepers, allowing a small but growing number to rise, within defined niches but keeping most out.

They should have kept me out. When I left journalism school in 1978, my function was defined as writing for people who bought ink by the barrel. Their messages, their stories, their opinions and their decisions about my future were what mattered, or so I was taught at Northwestern’s Medill School. If I wanted a career, my views would not matter. Public relations was considered a decent option.

Yet I’ve persevered. Thanks to technology, thanks to this Internet, from which I have earned my bread since 1985. These words you are reading right now are testament to that fact.

The point is that when technology closes doors, it also opens windows. What young people need to know, desperately, is that there are open windows, and they need to learn how to open them. The aim is not “jobs,” but “careers.” They need to know that what you do, what you are, will be based on what you think, and your commitment to it, not what some employer thinks. Human capital is the coal of the 21st century, and we need better stuff.

Everyone needs to be an entrepreneur in the 21st century. Is that being taught in schools? In colleges? No. It’s not. Kids are being taught the opposite. Even our best colleges are focused on jobs, not careers, and on comfort, not success

This is an essential point, because unless young people understand that their passion can drive them to comfort, far more than their allegiance, they’re unlikely to support the changes that are inevitably coming. What happens when jobs as truck drivers, ambulance drivers, and even ambulance chasers disappear, as they will in just the next decade?

I will talk about this more in the weeks to come, but let me conclude this essay with a thought project. When the Democrats meet in Philadelphia this summer, and Hillary Clinton takes her bows as the party’s standard bearer (the Bern having gotten burned by California tech money), who do you see standing next to her? A standard politician? A Democratic party stalwart?