On most issues the politicians representing TechLand are right and those of Trumpistan are simply wrong.

On most issues the politicians representing TechLand are right and those of Trumpistan are simply wrong.

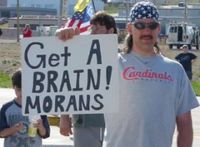

It’s not that Trumpistan lacks answers. The trouble is they don’t know the questions. Trumpistanis believe a politics of nativism, populism, and militarism can save them from the forces of change battering down their suburban splendor. They can’t, because politics had nothing to do with it. What is happening is that the same technological forces that built those suburbs now demand new economic structures, built around software and research, and the need for trained minds to be in constant contact, 24-7 rather than 9-5.

Bankers and insurance agents, the middlemen who held the country together through the 20th century, are no longer needed in the 21st. They’re like John Henry, the steel-driving man. They’re coal miners, they’re auto workers, they’re ditch diggers, they are in the way, and they are being replaced by machines.

What’s needed, in the 21st century, are agile minds. Not just trained minds, but minds that can understand new problems, come up with new solutions, and adapt themselves to a process of rapid, accelerating technological change, the kind of rapid change required to prevent the old ways from making this planet uninhabitable by modern man.

What’s needed, in the 21st century, are agile minds. Not just trained minds, but minds that can understand new problems, come up with new solutions, and adapt themselves to a process of rapid, accelerating technological change, the kind of rapid change required to prevent the old ways from making this planet uninhabitable by modern man.

To that end, TechLand says, we need better education. True, so far as it goes. But the kind of education system they’re talking about is as obsolete as the insurance agency.

Our education models have not changed in over a century. They do not take advantage even of the PC, let alone clouds and devices. And their aim is wrong. Educators focus on curriculum, when what people need are the mental and emotional tools to turn their lives into their own curriculum. Colleges focus on getting people ready for jobs, when what they should be doing is mentoring people to create careers and discover themselves.

Some of the difficulty, on the local level, comes from Trumpistanis. Parents should not be defining what’s taught. Students should not be learning any specific thing, but about how to learn. They need emotional defenses against rapid change, as well as intellectual curiosity throughout their lifetimes.

Some of the difficulty, on the local level, comes from Trumpistanis. Parents should not be defining what’s taught. Students should not be learning any specific thing, but about how to learn. They need emotional defenses against rapid change, as well as intellectual curiosity throughout their lifetimes.

More of the difficulty comes from the Left. Unions are inherently conservative institutions, wanting only more for their members in exchange for doing the same thing. Teachers’ unions are no different. They defend the present brick classroom structures as their fathers defended the auto plants and their grandfathers defended the coal mines.

How we teach must change fundamentally, as must what we teach. When I was on the education technology beat two decades ago teachers had a phrase for it – out with the sage on the stage, in with the guide at the side. Teachers need to get out of the business of presenting information, and testing mastery of information, and get into tutoring. That’s because presentation and technology can be done, easily, and with much greater accuracy, by machines.

As bad as these problems are in K-12 education, they’re worse in college. Both my kids have gotten out recently and I know. College teachers are teaching a curriculum. They’re not teaching the basic skills of thinking. And they’re pre-occupied either with teaching or their own research, when they need to be far more deeply involved in their students’ lives, helping them identify talents and interests, nurturing them, and mentoring them so they can be turned into meaningful careers.

Teachers teach. Mentors empower. Teachers can make you what they are. Mentors can help you become what you are.

Most state-run schools don’t mentor. Some do. Those involved in research have teachers who are looking for the next generation to support them, and eventually to replace them, in their chosen fields. But most state schools are no better than high schools, running through a defined curriculum with poorly trained graduate students in front of blackboards, and exams taken with number two pencils. The graduation ceremony, the happy graduate standing in the mortarboard, is their output. After that the kid is on his or her own.

No one in my daughter’s school told me she had dyslexia. No one in my son’s school told me about his Asperger’s. No one even suspected it. Teachers are taught that all students are alike, when in fact every student is unique, different, and needs to be taught and nourished in that. Because that’s where talent comes from, it’s a unique spark in each of us, and it’s expressed when work becomes play. This is true in every subject. Many teachers understand this, but they’re bound by bureaucracy to ignore it.

During my lifetime we have turned many jobs that should only be learned on the job into degree programs, for no better reason than to create jobs for the unimaginative and empires for the tired and lazy. If you want to learn to cook, start by washing dishes in a good restaurant. If you want to be a musician, shut up and play.

Employers can share the blame. They demand specific skills, boxes checked on the candidates they let in. And once the business changes, so those skills are no longer useful, they dump those people and get new ones. My wife wasn’t even trained, at first, in computer programming. Her first language was Assembler. But, fortunately, she was able to learn Cobol, then how to write functional specifications. She is now worth a fortune organizing and optimizing the work of other programmers. Very few people get those opportunities. Everyone deserves them. Learning must be a lifelong process.

As I said, technology is going to drive these changes. Politics won’t do it. But politics can decide just how much collateral damage, in the form of destroyed lives and careers, is left behind. We need to redefine education, first from mastering any curriculum to mastering the process of learning, and enjoying it. We need to transform colleges from places that mass produce credentials into lifelong learning centers that nourish people, and from which no one ever graduates.

Hi Dana,

I’m little confused here. Love your blog by the way…I agree that highly structured education may serve as a hindrance to the creative types—writers, musicians, designers (both online and offline). However, I was always under the impression that hard core computer science was cut and dry. Now, I understand that change happens in any line of work, but I always figured that a good old fashioned attitude towards learning new things would counter stagnation. I guess this is what your article is driving at?

Thanks,

William Bias

Hi Dana,

I’m little confused here. Love your blog by the way…I agree that highly structured education may serve as a hindrance to the creative types—writers, musicians, designers (both online and offline). However, I was always under the impression that hard core computer science was cut and dry. Now, I understand that change happens in any line of work, but I always figured that a good old fashioned attitude towards learning new things would counter stagnation. I guess this is what your article is driving at?

Thanks,

William Bias