It died of a business model, they say. Advertising no longer pays the bills, and the damned readers refuse to pay like they did “back in the day.”

This is nonsense. Readers never paid for journalism. What they paid was the cost of getting the paper from a printing press to their front door, or into their hands at a newsstand. The printing, the paper, and the workers were always paid from the advertising in the paper, and due to the high costs associated with printing and distribution, editorial only got 8% of the budget anyway.

With the Web, most of those costs disappear. You no longer need the printing press. You don’t care about paper costs, or ink costs. All you need is a Web site, and there you get to take advantage of cloud economics. Reach and frequency are free.

No. If journalism is dead it is because it has lost its function, its true reason for being, no matter what lies they told you in journalism school.

Journalism is about making markets.

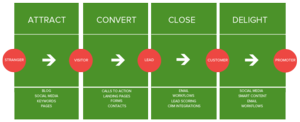

Back when the Web was spun, 20 years ago now, I asked publishers “how hungry” they were, because the Web allowed them to do more than post billboards along a defined roadway of editorial copy. The Web lets sellers take buyers all the way down a sales funnel. It lets them complete the transaction and perform post-sales service. The further a journal took readers down that funnel, I figured, the more value they created to these business partners.

They weren’t very hungry. They wanted to do business the way they had in print. They paid the price. So did all the people who worked for them.

The dirty secret of journalism is this. No one wants to buy advertising. It’s dead money. It’s a crapshoot. You are either pushing your name in front of people, or you’re selling specific products and services which you either made or bought for re-sale. What you wanted out of that spending is none of the metrics that people in the journalism business talked about – reach, frequency, impressions. What you wanted was to sell, to get people to sign on the line that is dotted. That is all.

So why aren’t journalists helping people sell stuff? That’s their business. It always has been.

No, they would rather sell advertising. But advertising is dead in the Internet Age. Thank Google.

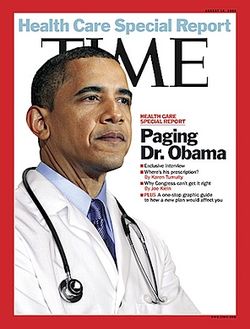

The result is that journals which depend upon getting a premium price for defined audiences in order to make the advertising model work are dying. The Google model, in which ad prices are constantly declining, favors “clickbait” news sites like Buzzfeed, which reflect the news rather than reporting. They copy, paste, and seek controversy. There can be only one winner in that kind of market. Everyone else is a loser. (That’s one of the features of the Web – it tends toward monopoly.)

Publishers have tried to fight back with paywalls, but once you put up a paywall you’re a newsletter. Paywalls can work only for highly-defined content you don’t want the world to know about, but not for broad content, and it then becomes a product which itself must advertise to find its market.

There are two ways out.

It’s time to try again, because it is now proven that Google destroys content through run of network pricing. If one ad on a page is worth X, two ads aren’t worth 2X, and 10 aren’t worth 10X. What we’ve seen is that 10 ads are basically worth X. The TV ad model proved that.

On today’s Web, TV is also cheaper to make than print. It also limits ad inventory organically. If you see more than one ad in front of a Web video, you click away and come to resent the advertiser. You may do that even with the one ad.

If a critical mass of Web publishers were willing to withhold their inventory, even reduce that inventory, and concentrate (through a third party so as to avoid anti-trust concerns) their defined audience power, they would stand a chance, because mainstream advertisers are finally on to Google’s game. They know most of what they’re buying is wasted, and that waste degrades the brand value of an ad, it doesn’t enhance it.

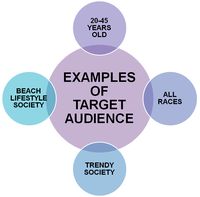

I have thought this would probably start with local Web sites, but I no longer think that. It’s far more likely to start with web sites devoted to passions, where the business partners are larger, but need the narrow tailoring of a defined audience to make their marketing pay. After all, the narrower your niche, the more the waste of a Google model diminishes you, because you have to buy more to get less.

And there’s always one other way out.

Journalism could simply die.

Great piece Dana…well said.

Great piece Dana…well said.