There can be no unlimited draw from a limited pool

The three corollaries are:

- Everyone gets into the pool, and everyone has skin in the game.

- Technology will show the best practices, and best practices should be followed.

- Competition is good.

The third corollary was put in by Republicans, whose allies have spent the last six years disproving it in their attempt to tear down the other corollaries and, in the end, destroy the Obamacare system.

Competition is good, but its aim is to win, and the prize for winning is market power, which the rules dictate must then be used on behalf of shareholders. Great in theory, but in practice inherently messy, and as subject to corruption as any government-run system.

Once this election is over we’re going to all face the problems of Obamacare beyond Obama, because we’re all getting older. Americans aren’t doing it as fast as Europeans or Asians, thanks to immigration, but we’re all doing it, each one of us.

![DANA AND JENNI 2009[1] DANA AND JENNI 2009[1]](http://www.danablankenhorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/6a00d83451da3169e201b8d1cb05f0970c-250wi.jpg)

In my own case, I’ve been fortunate that my dad’s high cholesterol and hypertension are now controllable by generic medication. The same is not true for the left-foot bunion I also inherited. The big toe is bone-on-bone, I can no longer run, and a lifetime of adjustment to that side means sciatic pain on the other side.

My partner in this life has learned that those bowlegs that attracted me to her also grind down knees. Her dad’s tendency to create fibrous cysts and fat deposits, along with a family history of breast cancer on her mother’s side, must also be dealt with.

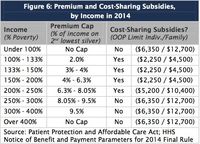

We have the “good” insurance. But good isn’t great. The main impact of Obamacare on our insurance has been to raise deductibles and co-pays. Before what should be routine tests, $1,600 in checks had to be written. The “good” insurance, paid for by employers, also leaves choices to patients they don’t know how to face, and it makes them easy prey for hospitals that resist change.

Most private hospitals don’t subscribe to this best practice. For the convenience of doctors, most private hospitals (both for-profit and non-profit) are surrounded by warrens of offices, with a variety of specialists, who have a variety of views, doing tests, diagnosis and treatment in isolation.

You feel a lump. Go to this person. But first get on the schedule. They do a test. You need a further test and wait a week for it, then another week for yet-another office to evaluate the results. Maybe, if you’re lucky, it’s nothing.

Competition, moreover, is not just about price. There are many dimensions to market competition. Brand and marketing are just two of the more wasteful dimensions. Then there is the creation of false need, which is where the ACA regime really breaks down.

In order to get the bill passed, Democrats had to accept that the drug approval process would remain as it was, and that Medicare, Medicaid, even private insurance groups, could not bargain on price. This means that once the FDA agrees that a drug or device works, its maker is free to sell it to anyone. They can name their own price, and so long as they convince a doctor to use it – by any means – it will be used.

There is a potential control. United Healthcare, while loudly proclaiming it’s leaving the Obamacare exchange, is actually doing this through a new unit called Harken Health. Kaiser Permanente and Intermountain have done this for years. New companies like Centene, which focus on Medicaid and Medicare patients, also do this.

You limit the network.

You tell patients that when you buy our insurance, you go to our primary care doctor. They will use data and best practices to get you the best care at the lowest cost, and focus on keeping you out of the hospital. When you need more care, you will go to the practices they contract with, at prices they negotiate.

This is the new business model built into the Obamacare system. Instead of charging a fee for each service performed, the new model is that insurers get a set amount of money each year, and if the patient gets through the year for less they profit. That’s change they can believe in. It’s incredibly valuable among the millions of people with chronic conditions like diabetes and kidney failure. These companies profit by getting people to comply with doctors’ orders. The employer-paid model profits more when they don’t.

This has to change. Data, science, and best practices need to drive decision-making, not the whims, gut instinct, or financial health of a particular practice. Insurers need more power to bargain with hospitals and clinics. They need to be able to actually buy hospitals, as well as clinics, and maintain patient control.

Sure, we need more information on pricing, and quality grades, and all of that. But mostly the health care system needs control and certainty. If you think I’m sick, tell me what I’ve got, as quickly as possible. Don’t leave me in suspense. Then get to work on it.

Cure me.

A good, informative article about a subject that had been previously very cluttered with misinformation. Thank you!

A good, informative article about a subject that had been previously very cluttered with misinformation. Thank you!