This only happens once in a generation. It is a climactic event.

Before validation, reporters and pundits will come to their work with an assumption that the political winds are blowing in one particular direction. After validation, they will always come to their work with an assumption that the political winds are blowing in a different direction. Their successors will take this new direction as a given.

After Nixon won in 1968, Democrats refused to believe for a decade that the New Deal Coalition was truly dead, and could not be recreated. The truth only dawned on them after Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1980, and his emphatic re-election in 1984, validated the strength of the Nixon Coalition. He had been considered extreme, “the man who nominated Goldwater,” and his natural caution kept him from entering the 1968 race until it was too late.

Hillary Clinton is more like a typical Validation candidate. She is Nixon-like in her tactical thinking, her natural diffidence. Just compare her to her husband, who created the Anti-Thesis to the Nixon thesis during the 1990s. Bill Clinton was a political natural, highly adept at swimming upstream to spawn. His charm overcame the fact that people were inclined to disagree with him.

We have had other Validation candidates, people who were elected because the political winds had shifted, who picked up the coalition of a crisis leader and rode the coalition, rather than their own personality, to power. Truman is one example. Taft was another. Grant was a third. None were political naturals, but all were the personal choice of the “Great Man” and thus of his coalition. Their record in office is mixed.

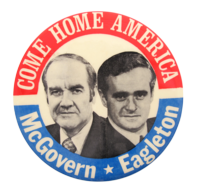

The 2016 election is a cross between the kind of party collapse we saw in 1972 with George McGovern, and the 1948 run of Thomas Dewey, who had already developed a sort of “anti-thesis” to the New Deal, an acceptance of many things FDR had done, but an insistence that he and his party could do them more moderately, more effectively, and do them for less. It would take Dwight Eisenhower to take this “anti-thesis” to power.

While most analysts still think of his impending failure as Goldwater-esque, however, his failures are more like those of George McGovern, who made the Democratic Party a minority party for a generation. Democrats go crazy separately, Republicans like to do it together, and Trump’s naivete, his pure will-to-power, his temperament, and his absolutism on important issues make him the most dangerous idiot a major party has ever put forward for President.

There are some rough analogs. Wendell Willkie was also a New York businessman who was unprepared to become President when the Republicans put him up against FDR in 1940. John W. Davis and Alton Parker were relative nobodies – extra credit if you even remember when they ran. We forget how ideological William Jennings Bryan was, how dangerous Populism was with its combination of egalitarianism, religion and bigotry. Bryan always played best in the rural South, with its fierce resentments and hatred of change. So does Trump. He’s the biggest Know Nothing since Millard Fillmore, who did indeed run on the ticket of a party by that name, in 1856.

The lesson of Trump would be clear if he were an ideologue like Ted Cruz. If his ideas were an extension of the crazy that had come before him, if that were pounded like a sack of millet this November, then Republicans would know where the lines of the crazy were drawn, and could create a candidate and platform that worked inside those lines as an effective anti-thesis. But he’s not. Republicans are very likely to treat his defeat as evidence that he was too liberal, too willing to accept the legitimate demands of the Republican base, and consequently to double-down on the real crazy they’ve been offering ever since Sarah Palin became a thing.

This election will validate the Obama Thesis of Consensus. Republicans who lie outside the consensus, like Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, will be swept far from power, often in unexpected ways. The dominant coalition of the current generation, which was the minority coalition of the last generation, will be in place, even without the politician who built that.

As for Hillary Clinton, and her husband, I see more difficult times. Validation leaders are not popular leaders. They are, of necessity, transactional rather than transformational. They are foxes, adjusting to every shift of the wind, rather than hedgehogs like Bernie Sanders whose very consistency gets them into trouble.

My guess is she will disappoint, and that Republicans will adjust, and that 2020 will be a very close election indeed.

But 2016 is all over but the shouting. And my hallelujah this November will be as loud as anyone’s.