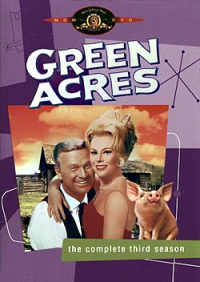

Shows like Green Acres.

Green Acres was the story of a lawyer, Oliver Wendell Douglas (that’s how we know he’s a lawyer), who decides to get away from it all by moving to the country. He was a success in the city, but here he is constantly humiliated by the locals upon whom he has made himself dependent. People like Mr. Haney, who had sold him the place, and Sam Drucker, who runs the general store. Even Eb Dawson, his farmhand, seems able to outwit him.

Green Acres is set in Greater Appalachia. It is less a place than a state of mind, a byword for white, rural poverty, the kind Democrats used in the mid-60s to sell Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Nixon and Norman Lear made everything more real. There was a “rural purge” of shows like Green Acres in 1971, poverty became a black and brown thing, and under the Nixon Thesis of Conflict, or Reaganism if you prefer, good people were to recoil from poor folks.

What if you were trying to make Green Acres today?

Most of our world would be easily recognizable to folks a half-century ago – cars are cars, homes are homes, and utilities are utilities. Hooterville, and the countryside surrounding it, would not look familiar. The Internet has transformed society, and made places like this redundant.

If one were creating an updated version of the show, Mr. Douglas would be a dot-com millionaire who could buy and sell the town, Mrs. Douglas a high-priced lawyer who could get his deals through any level of government, and the couple would act as Lords next to the peasants around them, barely acknowledging their existence.

As before, some of the show’s tension would involve the locals’ resentment of Douglas’ wealth, and the Douglas’ ignorance of that resentment. But in this version, the locals would be powerless. Some comedy would come from Douglas’ visiting friends, guest stars trying to open restaurants, coffee bars, B&Bs and art shops in town. There would be Asian or Mexican entrepreneurs, opening new businesses, taking what farm hand jobs that remained, bringing in relatives to work with them. Over time, the resentment would boil over. Mr. Drucker would run the Dollar General with a red hat reading “Make Hooterville Great Again.”

I see Hank Kimball as a DEA agent. One week he could be Inspector Javert to Eb’s Jean Valjean, Ralph Monroe singing “I Dreamed a Dream.”

Except for our bigger cities, and our larger university towns, America’s whole countryside is now Greater Appalachia. All the pathologies Trump voters associate with the Inner City – the guns, the drugs, the lack of jobs, the hopelessness – they’re drowning in it. But the people there don’t feel responsible for dealing with the pathology. It’s easier to project it all onto others, to find a politics aimed at deliberately pissing off liberals and to try and send the foreigners away, rather than dealing with the real problems.

Drive through a university town today and you’ll be in a larger version of Green Acres. The professors have their suburban homesteads, there are burger chains for the students and Wal-Marts for the townspeople. They’re little blue dots in a deep red sea.

This illustrates an important point. Science, especially social science, is inexact. That happened in the 1960s as well. Social science told politicians to build high rise apartments for the poor, that it would give them dignity, make them change. It’s good, meaningful work which does that. Poverty is in our hearts, not in our surroundings.

Trying to see this through the prism of comedy might help those of us in TechLand start to understand both what is happening, and how we can help. Family farming is dead, unless it’s highly artisanal, and the “farmers” are urban hipsters who can get top price for their product by selling directly to restaurants or through urban farmers’ markets. Commercial seed is genetically modified, planted without tilling by large machines, and combines handle the harvest as well. Most of the land is in very few hands, or corporate hands in big cities.

Greater Appalachia is occupied territory. That is why rural-oriented legislators have gerrymandered everything. By denying TechLand the vote, they halt its spread, slow the occupation. Investment that would have been welcomed a half-century ago, because it would bring good factory jobs, is now resisted because if you don’t have high-end skills you can’t earn a living wage. Not many people work in a data center.

Asheville, NC, a few hours’ drive from Atlanta, is an example of what can happen.

Gerrymandering means that the Asheville vote is split among several districts, the voices of the little blue dot aren’t heard in Raleigh. This gerrymandering extends to the cities as well. Even Raleigh’s voice isn’t heard in Raleigh.

This failure of democracy is slowing the growth of the little blue dots. I think that’s the point for Trumpistanis. Hooterville is determined not to be ruled by the Douglases, even if we are their only hope.

A surprisingly sensitive and clear-eyed essay… right up until the last seven words. It would be 100 times more effective without them, as they effectively cancel everything that went before.

A surprisingly sensitive and clear-eyed essay… right up until the last seven words. It would be 100 times more effective without them, as they effectively cancel everything that went before.

Well, “if”. Part of the problem is that we may not realize that if we come to them as their only hope, they’ll feel beholden to us, and they don’t want that. We have to approach them in such a way that they don’t feel beholden. Maybe then they’ll loosen their grip on political power.

Well, “if”. Part of the problem is that we may not realize that if we come to them as their only hope, they’ll feel beholden to us, and they don’t want that. We have to approach them in such a way that they don’t feel beholden. Maybe then they’ll loosen their grip on political power.